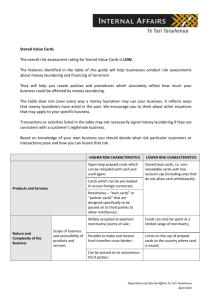

Corruption and illicit financial flows - U4 Anti

advertisement