Parts, Wholes, and Place Value: A Developmental

advertisement

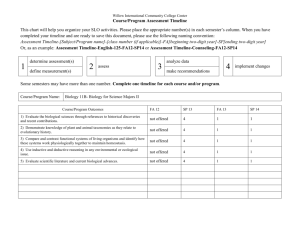

Parts, Wholes, and Place Value: A Developmental View Author(s): Sharon H. Ross Reviewed work(s): Source: The Arithmetic Teacher, Vol. 36, No. 6, FOCUS ISSUE: NUMBER SENSE (February 1989), pp. 47-51 Published by: National Council of Teachers of Mathematics Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/41194463 . Accessed: 10/09/2012 19:33 Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at . http://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsp . JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact support@jstor.org. . National Council of Teachers of Mathematics is collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to The Arithmetic Teacher. http://www.jstor.org Parts, Wholes, and Place Value: A Developmental View By Sharon H. Ross Whena studentmentally computes 32 + 59 bythinking 30 4-50 is 80,9 + 2 is 11, and80 + 11 is 91, thatstudent has had to call on some well-developed concepts of numericalpartwholerelationships and place value. Peoplewithgoodnumbersensemake and flexibleuse ofthesetwo frequent relatedconceptsto performmental and numericestimates. computations Studentsfindtheseconceptsdifficult; theirunderstanding develops slowly overa periodof severalyears.To be successfulat teachingnumbersense, we mustdesigninstruction that restudents' need to construct spects theirownknowledge. mentallyto compose wholes from theircomponentparts, decompose wholequantitiesintoparts,and perthe partsand recomhaps rearrange all confident pose thewholequantity, the while that the quantityof the wholehas notchanged. Place value and part-whole relationships of wholequanA naturalpartitioning used by those titiesthatis frequently withgood numbersense is that of "tens and ones"- or higherpowers of 10withnumberslargerthan99. To describedin use thekindof thinking the exampleof 32 + 59, a student a firm constructed musthavementally Part-Whole of the of understanding concept place value. Yet classroomteachersand Relationships observe that A pupil'snumerical awarenessdevel- researchersrepeatedly students' understandingof place ops gradually.Firstgradersexplore valueis poor. the varietyof ways in whichsmall Understanding place valuerequires 7 can be numbers can be partitioned; the student'semergan elaboration of as 3 + 4 as well as 1 + 6 partitioned of a part-whole ing understanding and2 + 5. As youngpupilsmaturein can be foundto Many ways concept. number senseand skills,theybecome ofa nummoreflexible.Theycan solve a wide forma two-waypartitioning + beras largeas 52: 51 1, 50 + 2, 49 ofverbaladditionandsubtracvariety + 3, 48 + 4, .... Onlyone ofthese, tion problems(Riley, Greeno, and + linkedto themeanstrat- 50 2, is directly Heller1983)anduse related-fact the individual of digitsin our ings egies to recallbasic facts(Cobb and notationalsystem.This conventional Merkel,in press; Thornton1978). is knownas a standard allowsthem representation theirthinking Eventually Nonstandard place-valuepartitioning. like 40 + tens-and-ones partitionings the 12 are useful in understanding SharonRoss is an assistantprofessorin the aspect of computational regrouping Caland statistics, ofmathematics department algorithms. Chico, Chico, CA iforniaState University, Ourrelatively elaboratenumeration 95929-0525. She teachescoursesforpreservice educators.She is mathematics and in-service systemis characterized bythefollowalso codirector oftheChicositeoftheCalifor- ingfourproperties: nia Mathematics Project,a summerinstitute 1. Positionalproperty. The quantiand leadership forteachers. training program February1989 tiesrepresented digbytheindividual itsaredetermined bythepositionthey holdin thewholenumeral. The valuesof 2. Base-tenproperty. thepositionsincreaseinpowersoften fromrightto left. 3. Multiplicativeproperty.The valueofan individual digitis foundby thefacevalueofthedigit multiplying by thevalue assignedto itsposition. .The quantity 4. Additiveproperty numeralis the whole by represented thesumof thevaluesrepresented by theindividual digits. To understand place value thestua andsynthesize dentmustcoordinate variety of subordinateknowledge aboutourculture'snotationalsystem for numbersand about numerical part-wholerelationships.A student who understands place value knows not onlythatthe numeral52 can be used to represent"how many"fora collectionoffifty-two objectsbutalso thatthe digiton the rightrepresents two of them,the digiton the left of them(fivesets of fifty represents 52 that is the sum of the and ten), by theindividquantitiesrepresented ual digits. A Research Study Using Digit-Correspondence Tasks withgoodnumber We expectstudents sense to have constructed meanings for numeralsin the initialyears of school.In a studyI conductedofthe meaningsthat studentsattributeto numerals,however,I found two-digit that many of them were still constructing meaningsfortheindividual 47 digitsas late as fifth grade (Ross 1985, 1986). In mystudyof sixtystudentsin second throughfifthgrade, randomly selected fromfivediverse elementary schools, students were individually administeredthe followingtask: Fig. 1 task materials Digit-correspondence The studentwas instructedto spilla sticks out collection of twenty-five of a bag, and I asked, "How many sticks are there?" Aftercounting, nearly all gave a correct oral response of "twenty-five." I then Many studentsare still constructing meaningforplace value infifthgrade. asked the child to writedown how many sticks had been counted. Nearly all correctlywrote the numeral25. 1 thenencircledfirstthe 5 and thenthe 2 and each timeasked, "Does thispartof yourtwenty-five have anythingto do withhow many sticksyou have?" Of the sixty studentsinterviewed, twenty-sixwere successful- theyexplainedin a varietyof ways thatthe 5 in 25 representedfiveof the sticksand thatthe 2 representedthe othertwenty. Twelve studentsthoughtthe individual digits had nothingto do with how many sticks were in the collection; fourteendescribed inventednumericalmeanings,such as that the 5 meant"half of ten," thatthe 5 meant that groups contained five sticks, or that the 2 meant "count by twos." Eight students thought that the 2 meanttwo sticksand thatthe 5 meant eitherfivesticksor had nothingto do withthe numberof sticks in the collections. In the stickstaskjust described,the collectionof stickswas notgroupedin any way. When the task was altered the number52 witha by representing standard place-value partitioningof base-ten blocks (five ten-blocks and two unit-blocks)many more of the students(44 out of the 60) were successful. But when 52 was represented usingfourten-blocksand twelve unitblocks, the numberof successful students dropped to twenty.Similar re48 sults were found in tasks in which a collection of forty-eightbeans was partitionedinto cups. Figure 1 displays the materials used in the six tasks used in the digit-correspondence study. Whydid childrenfindthe tasks that used a standardplace-value partitioning to be so much easier? In both standardtasks, the representationsof the groups of ten were very prominent. When, for example, I asked if the 2 and 5 in the numeral 52 had anythingto do with how many baseten blocks were on the table, the student was looking at five long purple ten-blocksand two tan unit-blocks.It is easy to see how the studentmight have proposed thatthe 5 represented the five purple blocks and yet have had no thought of tens or fiftyin mind- just fivepurple blocks. In a follow-up study designed to examinewhethersome studentsdid in fact use this face-value interpretation to assign meaning to the individual digits, thirty third-grade students were individuallyasked to count a collectionof twenty-sixobjects and to "write down how many." They were thenasked to sortthe objects intosets of four ("candies into party-favor ArithmeticTeacher objectspartitioned ^ Fig.2 Twenty-six ä /~' intosets offour ^ f~' ^ ^ ' QOJ cups" or "wheelsto maketoycars"). The resultingpartitioned collection, infigure 2, containedsix sets pictured of fourobjectsand two "leftover." The interviewer then encircledthe individual digitsin 26 and asked,for each digit,"Does thispartofyour26 have anything to do withhow many youhave?" The prominentgroupingsin this a correct task,insteadof facilitating an incorrectreresponse,facilitated sponse,wherestudentsreversedthe of thedigitsand wherethe meanings werenot in base ten. The groupings incorrect response,however,wasconsistentwiththeface-valueinterpretation.Nearlyhalfof thethirdgraders incorrectly respondedthatthe2 in 26 stoodfortwooftheobjects,whereas the6 in the 26 represented the "six cupsofcandies"or "the six cars." ^^ AX) 00 Stage 1, wholenumeral.As pupils in our cultureconstructtheirknowledge about quantitiesup to ninetynine and theirsymbolicrepresentation as two-digitnumerals, their of the whole cognitiveconstruction - the numeral52 reprecomes first sentsthewholeamount.Theyassign no meaningto the individualdigits. For related work that reportsobserveddifferences betweenpupilsin the U. S. and thosefromAsian cultures,see the workof Miura (1987) and ofMiuraet al. (in press). f Table 1 Stages intheDevelopmentofStudents' of Two-Digit Understanding Numerationby Grade in School Stage of development Grade* 2 3 4 5 Total 1 Π Ш 8 0 10 0 9 0 2 3 5 6 12 3 16 IV 4 6 17 5 16 V 0 2 7 16 *n = 15foreachgradelevel. trulyrepresent groupsof tenunitsto studentsin stage 3; studentsdo not Studentsin theirearlystagesof recognize that the numberreprevalue of sentedbythetensdigitis a multiple understanding ofplace to ten. appear understandmorethan do. zone. Stutheyactually Stage 4, construction dents know that the leftdigitin a numeralrepresentssets of two-digit ten 2, Stage positionalproperty. Pupils objects and that the rightdigit in numeral the know that a two-digit representsthe remainingsingleobStages of Interpreting the in the "ones on is digit right jects, butthisknowledgeis tentative Two-Digit Numerals in and the left is task the on andis characterized digit place" byunreliable the "tens of Their knowledge A five-stage place." performances. modelof the interpretahowevdigitsis limited, tionschildrenassignto two-digit nu- theindividual Students Stage 5, understanding. meralswas developedbased on data er, to the positionof the digitsand know thatthe individualdigitsin a fromthe originalstudyand findings does notencompassthequantitiesto two-digit numeralrepresenta partifromrelatedresearch(Ashlock1978; whicheach corresponds. tioningof the whole quantityintoa Baroody et al. 1983; Barr 1978; Stage3yface value. Studentsinter- tenspartand a ones part.The quanBednarzand Janvier1982;Flournoy pret each digitas representing the tityof objectscorresponding to each numberindicatedby its face value. digitcan be determined evenforcol1967;Heibertand Wearne 1983; M. Kamii 1980, 1982; NationalAssess- The set of objectsrepresented in by the lectionsthathave been partitioned mentof EducationalProgress1983; tensdigit,however,maybe different nonstandard ways. Rathmell1972; Resnick 1983; Rick- fromthe objects represented by the man 1983; Scrivens1968; C. Smith onesdigit.Theymayverballylabelas Ages and Stages to of "tens" theobjectsthatcorrespond 1969;R. Smith1973).Descriptions thetensdigit,buttheseobjectsdo not Each of the sixtystudentsin therethestagesfollow. February1989 49 for many portedstudywas assignedto one of fractions,is inappropriate the five stages accordingto perfor- students. mances on six digit-correspondence How do so manystudents reachthe tasksanda positional-knowledge task middlegrades with so littleunderinwhichstudents wereaskedto iden- standingof two-digit numbers?One in in tify, a two-digitnumeral,which reasonis thatpupils stages2 and 3 morethan digitwas in the "tens place" and mayappearto understand whichwas in the "ones place." The theyactuallydo. Withstage-2knowlnumberof studentsin each stageis edge of theleft-right positionsof the shown,by gradelevel,in table 1. Althoughall the studentsin this studywereat leastat stage1- able to Each pupil mustbe provoked countcollectionsof as manyas fiftyhis or her own two objects and writethe two-digit intoconstructing numbers and the numeralthat correspondedto the knowledgeof count twelveof themdemonstrated relationsamongthem. no quantitative of the interpretation individual digits. Sixteenstudents succeededonlyon digits,pupilsare able to succeedon a those digit-correspondence tasks in varietyof tasks typicallyfound in whichnumberswererepresented us- theirtextbooksand on standardized inga standard place-valuepartitioning tests,suchas thefollowing: of a collectionof objects- that is, In 27, whichdigitis in the tens those tasks in whichtheycould be place? successfulusinga stage-3face-value How manytensare in 84? interpretation. Sixteenstudentssucceededon all 35 = tensand ones. six digit-correspondence = tasks,dem7 tens+ 5 ones a stage-5understanding of onstrating Studentswho use a stage-3,facethenumbersrepresented by theindivalue of digitssucceed interpretation vidualdigitsin two-placenumerals. on an even wider varietyof tasks, No second-grade pupildemonstrated that use manipulative many Even among including stage-5understanding. materials. In instructional tasks many the fifthgraders,only halfwere at students are asked to make correstage5. spondencesbetweendigitsand materials.Ifa collectionis alreadygrouped intoa standardplace-valuepartitionImplications forthe ingoftensand ones,a studentwhois Classroom asked to make correspondences for the in for need 52, digits example, More instructional supportfocusing and onlylook for"fiveof something on two-digit numeration is neededin themiddlegrades.Studentsdo notall developat thesamerate,nordo they all have identicalexperienceswith Whena teachershowsstudents numbers and numerals.The data disstudentsdo nothave something, in played table 1 show thateven in to think;theysimplyfollow fourth and fifth grades,onlyhalfthe directions. studentsintervieweddemonstrated of the individual good understanding numerals.Others digitsin two-digit who have used digit-correspondencetwo of something else." Using this tasksto assess students'understand- face-value strategy, a studenteasily - beans in ing of place value reportsimilarre- adapts to new materials sults(C. Kamii1986;M. Kamii1980, cups, linkingcubes, base-tenblocks, 1982).Thetypicalplace-valueinstruc- or coloredchips,forexample.Only tionin the middlegrades,whichfo- whenthecollectionsare groupedinto cuses on symbolicexpressionsfor nonstandardpartitionings does stumuchlargernumbersand on decimal dents' face-value interpretation fail 50 with them;whentheyare confronted tasks,students'faultyunregrouping becomesapparent. derstanding Further studyneedsto be done,but even extensiveexperiencewithembodimentslike base-tenblocks and otherplace-valuemanipulatives does notappeartofacilitate an understandingofplace valueas measuredbythe digit-correspondencetasks (Ross 1988).If we introducematerialsthat have been designedto embodybaseten groupingsbeforestudentshave constructedappropriatequantitative fortheindividual meanings digits,we mayunwittingly provokeor reinforce a stage-3(face-value)interpretation of digits. With these materials the teacherand manufacturer may have "embodiedtheten," butthe student neednot. materials can serveas Manipulative a usefulcommunication toolbetween - they give us teacher and student to talk about. something Throughthe use of such materialswe can often learn a great deal about students' thinking, includingtheirmisconceptions(Labinowicz1985).We can also use thematerials to showand explain whatwe wantstudents to do. Careful instruction withplace-valuemanipulativescan facilitatethe acquisitionof the proceduralknowledgerequired forfacilitywithcomputational algorithms(Fuson 1986; Resnick 1983). We should not mislead ourselves, however,thatas a resultof such instructionstudentsconstructunderstandingofeitherthecomplexplacevalue numerationsystem or the is the algorithm.If understanding goal,itprobablydoesn'tmatterifthe teacher shows childrenprocedures with paper and pencil, beans and cups, or base-tenblocks. When a teacher shows studentssomething, studentsdo not have to think;they simplyfollowdirections. comes only from Understanding each thinking; pupilmustbe provoked into constructinghis or her own knowledgeof numbersand the relationsamongthem.Pupilsneedto entasks that gage in problem-solving them to think about useful challenge to and ways partition composenumbers.The additionand subtraction of numbersthroughninety-nine are apArithmetic Teacher propriate topicsfor second graders, butwe shouldencouragepupilstofind in theirown sums and differences ways. For studentswho have not been taughta conventionalpaper-andthe sum of pencilprocedure,finding 32 + 59 is a nonroutineproblem whosesolutionstrategy is notreadily The can apparent. problem be solved usinga varietyof strategiesand a - counters,finvarietyof materials and or gers, paper pencil.If theyare in working cooperativegroups,studentscan be encouragedto compare methodsand tryto convinceone andoes or doesn't otherthata strategy use "work"; theymight a calculator to verifythe solution.In the larger group discussion,studentscan be theirsuccessful askedto demonstrate strategies. Teaching place-value concepts to doubleas a prerequisite separately is inefdigitadditionand subtraction fectiveand unnecessary. Experimental instructional studieshave shown thatpupilsin firstand second grade can inventtheirown efficient algoanddo so without rithms, place-value manipulatives(Kamii and Joseph 1988;Cobb and Merkel[inpress]).In materials fact,manipulative mayactudetract from thinkingbecause ally tasks are too easy to do with the materials. As teachers of mathematicswe forall need to provideopportunities students to developa strongsense of number.To accomplishthatgoal we can help each studentto construct as she or he matures,inmentally, elaborateconceptsof nucreasingly andplace relations mericalpart-whole value. If we challengestudentswith for makingestimoreopportunities and matesand mentalcomputations show them the conventionalalgorithmsonly aftertheyhave experienced a fertileperiod of inventing theirown efficientproceduresfor like32 + 59,we can solvingproblems expectmoreyoungstudentsto demflexthenumeric onstrate partitioning of those ibilitythatis characteristic withgood numbersense. If students thenlearna conventional algorithm, theywillviewitas one ofmanyways to finda sumor difference; they'llbe February1989 able to choose fromand use, as apmentalcompuestimation, propriate, tation,and calculators,as well as inventedand conventional algorithms. Labinowicz, Ed. Learningfrom Children. MenloPark,Calif.:AddisonWesleyPublishingCo., 1985. Achievement as Miura,IreneT. "Mathematics a FunctionofLanguage."JournalofEducationalPsychology 79 (March1987):79-82. References Chih-Mei Miura,IreneT., KimC. Chungsoon, Ashlock,RobertB. "Researchand DevelopChang,and Yukari Okamoto."Effectsof on Children's mentRelatedto LearningaboutWholeNumLanguageCharacteristics CognitiveRepresentation of Number:Crossbers: Implications for Classroom/Resource NationalComparisons." ChildDevelopment. In TopicsRelatedto DiagnoRoom/Clinic." In press. sis inMathematics forClassroomTeachers, editedby M. E. Hynes. Kent, Ohio: ReNationalAssessment of EducationalProgress. searchCouncilon Diagnosticand PrescripThe ThirdNational MathematicsAssesstive Mathematics,1978. (ERIC Document ment:Results,TrendsandIssues. Princeton, ServiceNo. ED 243694) Reproduction N.J.:EducationalTestingService,1983. J.,KathleenE. Gannon,Rusti Baroody,Arthur EdwardC. "The Effects ofMultibase Rathmell, Berent,and HerbertP. Ginsburg."The Deof and Earlyor Late Introductions Grouping of Basic FormalMathAbilities." velopment Base Representations on theMasteryLearnoftheSociety at themeeting Paperpresented in ingof Base and Place Value Numeration forResearchin ChildDevelopment, Detroit, InternaGradeOne." Dissertation Abstracts April1983.(ERIC DocumentReproduction tional33 (May 1972):6071A. Serviceno. ED 229 153) Resnick,LaurenB. "A Developmental Theory ofThreeMethBarr,DavidС "A Comparison In TheDevelopofNumberUnderstanding." Numeration." ods of Introducing Two-Digit mentofMathematical editedbyH. Thinking, EducaJournal forResearchinMathematics P. Ginsburg,110-51.New York:Academic tion9 (January 1978):33-43. Press,1983. Bednarz, Nadme, and BernadetteJanvier. Rickman,Claude M. "An Investigation of in Priof Numeration "The Understanding Thirdand FourthGrade Students'UnderAlmarySchool." EducationalStudiesinMathofa Decomposition Subtraction standing ematics13 (February1982):33-57. gorithmBased on IndividualInterviews." Dissertation Abstracts International44 Cobb, Paul, and GraceannMerkel."Thinking as an ExampleofTeachingArith(1983):1365A. Strategies meticthrough ProblemSolving."In ElemenRiley,MaryS., JamesG. Greeno,andJoanI. Issues and DirecHeller. "Developmentof Children'sProbtarySchoolMathematics: In The tions,1989YearbookoftheNationalCouncil Abilityin Arithmetic." lem-solving of Teachersof Mathematics.Reston,Va.: edThinking, Development ofMathematical The Council.In press. 153-96.New York: itedby H. P. Ginsburg, AcademicPress,1983. Cobb, Paul, and Grayson Wheatley. of Ten." "Children'sInitialUnderstanding ine Development oi Koss, Sharon H. ofthe at theannualmeeting Children'sPlace-Value NumerationConPaperpresented ResearchAssociation, American Educational Five." Paper ceptsin GradesTwo through oftheAmerat theannualmeeting D.C., April1987. Washington, presented ican EducationalResearchAssociation,San UnderA ot Frances. btudy Pupils Mournoy, Francisco,1986. (ERIC DocumentReprostandingof Arithmeticin the Primary ductionServiceno. ED 273482) Teacher 14 (October Grades." Arithmetic PlaceofChildren's . "The Development 1967):481-85. Value Numeration Conceptsin GradesTwo and Fuson, Karen. "Roles of Representation of throughFive." Ph.D. diss., University Verbalization in theTeachingof Multi-Digit AbCalifornia, Berkeley,1985.Dissertation Additionand Subtraction." EuropeanJourAl (1985):819A. stractsInternational nal of Psychologyof Education 1 (1986): 35-56. . "The Roles ofCognitive Development of in Children'sAcquisition and Instruction нетеп, James,ana Diane wearne. òiuaenis Numeration PlaceValue Paper Concepts." Numbers." of Decimal Paper Conceptions oftheAmerpresentedat theannualmeetingof theNaat theannualmeeting presented tionalCouncilof Teachersof Mathematics, ican Educational Research Association, Chicago,April1988. Montreal, April1983. Studyof Scrivens,RobertW. "A Comparative Kamii,Constance."Place Value: An ExplanatoTeachingtheHinduDifferent forthe Approaches tionofIts Difficulty and Implications ArabicNumeration Systemto ThirdGradGrades." Journalfor Researchin Primary 29 (1968):839A. Abstracts ers." Dissertation Childhood Education1 (August1986):75-86. of Constant "A Charles Jr. W., Smith, Study "The and Linda Kamii, Constance, Joseph. and in theApplication Errorsin Subtraction TeachingofPlace ValueandDouble-Column oftheDecimalNumerofSelectedPrinciples Teacher35 (February Addition."Arithmetic ation SystemMade by Thirdand Fourth 1988):48-52. InAbstracts GradeChildren."Dissertation Kamii,Mieko."Childrens GraphicRepresenMi30 (1969):1084A.(University ternational tationof NumericalConcepts:A Developno. 69-14685) crofilms InterAbstracts mentalStudy."Dissertation F. "Diagnosisof PupilPerforRobert Smith, national 43 (November 1982):1478A. mance on Place-Value Tasks." Arithmetic no. DA 8223212) Microfilms (University Teacher20 (May 1973):403-8. . "Place Value: Children'siittortsto betweenDigitsand Finda Correspondence Thornton,Carol A. "EmphasizingThinking at the JourNumbers ofObjects."Paperpresented in Basic Fact Instruction." Strategies oftheJeanPiaget Education9 TenthAnnualSymposium nalforResearchinMathematics May 1980. Society,Philadelphia, (May 1978):214-27. Щ 51