CAPITAL, FRACTIONS OF CAPITAL AND THE STATE `NEO

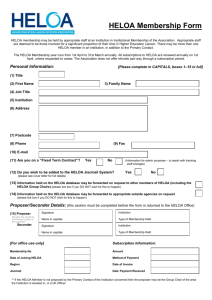

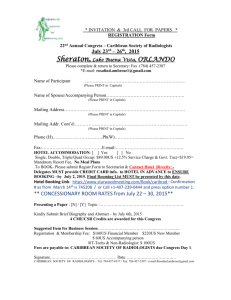

advertisement