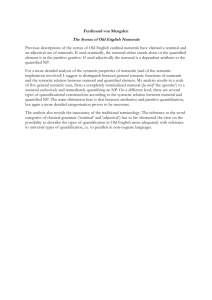

Reference to numbers in natural language

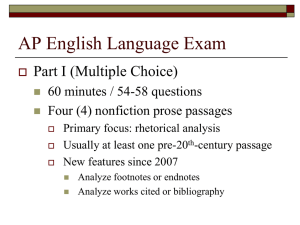

advertisement