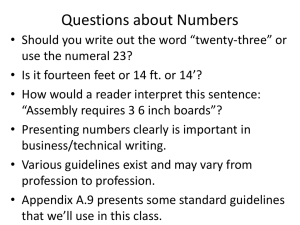

Nouns and adjectives in Numeral NPs

advertisement

Nouns and Adjectives in Numeral NPs

Overview Recent work by Ionin & Matushansky (2004) argues, primarily on semantic grounds,

that numerals should not be considered determiners or syntactic heads, but rather nominal

modifiers. They further show that complex numeral phrases, both multiplicative ('three hundred')

and additive ('a hundred and three') are derived in the syntax rather than the lexicon, resulting in

structures as in [T1]. However, in treating all numerals alike, they do not address one of the most

puzzling generalizations about the syntax of numerals: in many languages, the simple numerals

do not show the properties of a single syntactic category. Rather, lower numerals tend to share

syntactic and morphological properties with adjectives, while higher numerals tend to exhibit

properties associated with nouns (see Corbett (1978)). I propose a modification of the Ionin &

Matushansky analysis that takes this difference into account, and further serves to tie the syntax

of numerals with recent analyses of quantity words such as few and many (Kayne (2002,2003)).

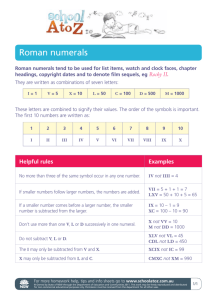

The Data In many Bantu languages, numerals lower than a certain threshold (often 5 or 10,

though much variation exists) agree with the noun they modify, featuring adjectival or

enumerative agreement prefixes [1]. Higher numerals do not agree, instead featuring their own

nominal class prefixes [2]. That this behavior is truly nominal can be seen in multiplicative

complex numerals such as [3], where the multiplier agrees with the numeral it modifies rather

than with the head of the DP. In English, starting with hundred, numerals can appear in plural

form in partitive constructions [4], can take determiners [5] and can be modified by other

numerals [6]. In Modern Hebrew, numerals up to 19 agree in gender with the head noun [7], but

higher numerals do not [8]. Similar patterns can be found in many other languages.

Analysis: Kayne (2002, 2003) provides a detailed argument that shows that few and many are

adjectives, but instead of modifying nouns directly, they modify an unpronounced noun which he

terms NUMBER, and in turn, the whole NUMBER NP modifies the noun, as in [T2], which explains,

among other things, why, even though every normally modifies only singular NPs, it can modify

phrases such as few days, as in [9]. Extending his proposal to numerals is a natural step, and

would help explain the puzzle above. Under this analysis, numerals are NPs. The low, adjectival

numerals such as three take the form [NP [AP three] NUMBER], while higher numerals feature an

overt noun, as in [NP [AP three] thousand]. This analysis is supported by evidence from a

variety of languages. In English, where numerals such as hundred normally appear in singular

form, it is possible to modify them by every even though the head noun is plural, as in [10]. In

Hebrew, however, the equivalent of hundred appears in plural; and can only appear concurrent

with every if the head noun is singular [11]. Adjectival numerals, however, freely appear with

every [12] as NUMBER is singular. Another piece of evidence can be found in the Bantu language

Luvale. In additive complex numerals in Luvale, the head noun can be appear in each member of

the conjunction, as in [13] (thus showing that additive complex numerals are formed by

conjunction of the whole NP, not just of the numerals; see Ionin & Matushansky (2004)). Also,

in this language the numeral for 6 is formed by a conjunction of two adjectival numbers, 1 and 5.

Note, however, that the head noun does not appear within this conjunction [14]. This supports

the structure in [T3] as opposed to a three-way conjunction (fifty and five and one).

Conclusion This proposal extends Kayne's (2002,2003) account of few and many in a manner

that is compatible with Ionin & Matushansky's (2004) semantics. It draws its support on a variety

of cross-linguistic data, some of which has been presented above, and shows how an apparent

asymmetry in the structure of low versus high numerals in many languages can be accounted for

in a single structure.

1.

2.

3.

4a.

b.

5a.

b.

6a.

b.

7.

8.

9.

10.

11.

12.

13.

14.

emi-dumu e-biri

MI-jug

AGRMI-two

'two jugs'

emi-dumu mu-sanvu

MI-jug

MU-seven

'seven jugs'

emi-dumu ama-kumi a-biri

MI-jug

MA-ten

AGRMA-two

'twenty jugs'

hundreds of boys

*threes of boys

a/several/hundred boys

*a/several three boys

four hundred boys

*four three boys

shlosha

yeladim /*yeladot

three-MASC boys/*girls

'three boys'

shloshim

yeladim/yeladot

thirty

boys/girls

'thirty boys/girls'

Every few days, John visits his mother.

For every hundred dollars I spend, I get ten back as a rebate.

kol shlosh meot

yom/*yamim...

every three hundreds day/*days

'every three hundred days'

kol shalosh *yom/yamim...

every three *day/days

'every three days'

Luganda

mikoko makumi atanu na-mikoko vatanu

sheep ten

five and-sheep five 'fifty five sheep'

mikoko makumi atanu na-mikoko vatanu naumwe

sheep ten

five and-sheep five and-one 'fifty six sheep'

Luvale

NP

T1.

T2.

NP

N

Two

N

hundred

NP

English

English

English

Modern Hebrew

Modern Hebrew

English

English

Modern Hebrew

Modern Hebrew

Luvale

NP

NP

Adj

few

N

NUMBER

dollars

NP

sheep

Luganda

NP

dollars

NP

T3.

NP

Luganda

Adj

atanu

NP

NP

NP

N

maku

na

NP

Adj

Adj

vatanu na umwe

sheep

N

maku

References:

Corbett, G.G. 1978. Universals in the Syntax of Cardinal Numerals. Lingua 46, 355-368.

Ionin, T. & Matushansky, O. 2004. A Healthy Twelve Patients. Paper presented at GURT 2004.

Kayne, R. 2002. On the Syntax of Quantity in English. NYU Ms.

Kayne, R. 2003. Silent Years, Silent Hours. NYU Ms.