Managing the United States-Mexico Border

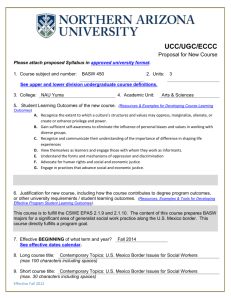

advertisement