The lore of prime numbers - Department of Mathematics and Statistics

advertisement

$

'

The lore of prime numbers

P.J. Forrester

Australian Professorial Fellow

Supported by the Australian Research Council and

The University of Melbourne

&

1

%

'

General audience references:

“Dr Riemann’s zeros” by Karl Sabbagh (Atlantic Books, 2002).

“Prime Obsession: Bernhard Riemann and the greatest unsolved

problem in mathematics” by John Derbyshire (Joseph Henry Press,

2003).

$

Primes

• Whole (natural) numbers greater than or equal to 2, which cannot

be factorized into a product of smaller whole numbers.

2 3 5 7 11 13 17 19 23 29

...

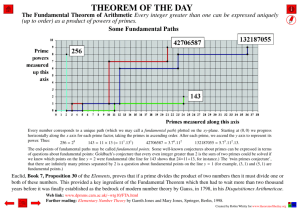

• (Euclid) Every natural number can be factored uniquely into a

product of primes.

24 = 4 × 6 = 3 × 8 = 23 × 3.

• (Euclid) There are infinitely many primes.

Proof by contradiction.

Suppose the list of primes was finite.

2

3 5 7

Argue that then

2×3×5×7+1

is prime but not in the list.

This is a contradiction.

Hence the list of primes in not finite.

Remark

&

2 × 3 × 5 × 7 × 11 × 13 + 1 = 30031 = 59 × 509.

2

%

$

'

Listing primes: the sieve of Eratosthenes

Write down the numbers 1 to 100.

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11 12 13 14 15 16 17

18 19

20

21 22 23 24 25 26 27

28 29

30

31 32 33 34 35 36 37

38 39

40

41 42 43 44 45 46 47

48 49

50

51 52 53 54 55 56 57

58 59

60

61 62 63 64 65 66 67

68 69

70

71 72 73 74 75 76 77

78 79

80

81 82 83 84 85 86 87

88 89

90

91 92 93 94 95 96 97

98 99 100

Remove from this list all multiples of the first prime number 2.

11

21

31

41

51

61

71

81

91

2

3

·

13 · 15 · 17

· 19 ·

33 · 35 · 37

· 39 ·

·

·

·

·

·

·

·

·

·

5

·

7

23 · 25 · 27

43 · 45 · 47

53 · 55 · 57

63 · 65 · 67

73 · 75 · 77

83 · 85 · 87

93 · 95 · 97

·

9

·

· 29 ·

· 49 ·

· 59 ·

· 69 ·

· 79 ·

· 89 ·

· 99 ·

Now remove all remaining multiples of the second prime number 3.

&

3

%

$

'

2

3

11

·

13 ·

·

·

31

·

41

·

·

·

61

·

71

·

·

·

91

·

·

7

23 · 25 ·

·

·

·

5

· 17

·

· 35 · 37

43 ·

· 47

·

53 · 55 ·

·

· 65 · 67

73 ·

· 77

·

83 · 85 ·

·

·

·

· 95 · 97

·

·

·

· 19 ·

· 29 ·

·

·

·

· 49 ·

· 59 ·

·

·

·

· 79 ·

· 89 ·

·

·

·

Continue in this fashion, removing all multiples of the prime numbers

up to ten: 2, 3, 5, 7.

2

3

11

·

13 ·

·

·

31

41

·

61

71

·

·

·

·

·

·

·

·

·

· 5 ·

23 ·

·

·

43 ·

53 ·

·

·

73 ·

83 ·

·

·

7

·

·

·

·

· 17 · 19 ·

·

·

·

· 29 ·

· 37 ·

·

·

· 47 ·

·

·

·

·

·

·

·

·

· 59 ·

·

· 67 ·

·

·

·

·

·

·

· 79 ·

· 89 ·

· 97 ·

·

·

·

·

This leaves us with all the primes up to 100. We count 25 such numbers.

&

4

%

$

'

One (of many) unsolved problems about primes

• (Goldbach’s conjecture) Is every even integer n ≥ 4 the sum of two

primes?

&

4=2+2

6=3+3

8=3+5

10 = 5 + 5

12 = 5 + 7

14 = 7 + 7

5

%

$

'

“How frequent are the primes?”

• Out of the first 102 natural numbers, 25 are prime: 1 in 4.

• Out of the first 104 natural numbers, 1229 are prime: 1 in 8.1.

• Out of the first 107 natural numbers, 664,579 are prime: 1 in 15.

• Data suggest — up to 10n , about one in every 2.3n are prime.

Legendre’s logarithmic law

Out of the first N natural numbers, roughly 1 in log e N are prime.

Gauss’ improvement

• The density of primes about the number N is approximately

Hence, out of the first N natural numbers, approximately

Z N

dt

loge t

2

1

loge N .

are prime.

&

6

%

$

'

Graph of

Z

|

N

2

dt

log t

{z e }

−(number of primes less than or equal to N )

logarithmic integral

as a function of N .

150

125

100

75

50

25

50

100

150

units of 10^4

200

The Riemann hypothesis

• The number of primes less than or equal to N , for N large, is given

by

logarithmic integral + correction term

where

correction term ∝

&

7

√

N loge N.

%

$

'

Interpretation and consequence

•

√

N corrections are familiar in probability theory.

• Kramer’s model — Statistical properties of primes are well

described by the statement that each positive integer n ≥ 2 is a

prime with probability 1/ log e n.

Numerical experiment

List say 2, 000 primes starting from the first prime bigger than 10 9 .

These are the numbers 109 + x with x equal to

7, 9, 21, 33, 87, 93, 97, 103, · · ·

What is the distribution of the gap between primes?

p^{(N)}(0;s)

p^{(N)}(1;s)

0.7

1

0.6

0.8

0.5

0.6

0.4

0.3

0.4

0.2

0.2

0.1

1

&

2

3

4

8

s

1

2

3

4

5

s

%