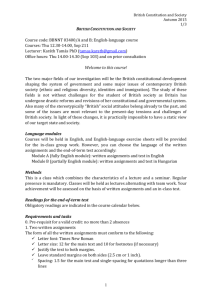

Power, People and Places

advertisement