Lady, Witch, and Immaculate Conception

advertisement

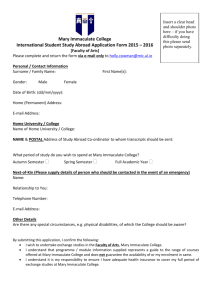

Lady, Witch, and Immaculate Conception While in graduate school in the early 1970s, a feminist consciousness was a novelty for my theology professors. What they taught as significant Western Christian church history looked increasingly like Swiss cheese. The institutional authority of male clergy was accepted without any sociological or psychological critique. The worst—but most entertaining—were the biases of medieval clergy, which, unfortunately, Western civilization inherited. I had particularly fun deconstructing three medieval views of woman. I n southern Europe at the end of the 11th century, an odd syncronicity began to develop. Three concurrent themes in medieval thought emerged and evolved together over the next three centuries:1 1) the idealization of the “Lady” from troubadour poetry on courtly love; 2) the doctrine of “Immaculate Conception” and the cult of Mariology; 3) and superstition about witchcraft and the persecution of “Witches.” The exact origin of each is somewhat uncertain. Nevertheless, the relics of each survive in old-style manners, in pious devotion, in parochial attitudes, and in prejudice. However, my concern is not with the origins of these medieval views of woman but with their synergistic development in southern Europe between the 12th and 15th century. In fact, their origins may be unknown precisely because they reside in each other—a co-dependent synchronicity. Any inaccurate characterization will breed another inaccurate characterization in counter-balance. Neither represents reality and thus needs another to approximate a truth. Yet dualism itself is a dynamic state; bifurcation tends to alternation. Thus, two opposing views bounce back and forth in social debate. In contrast, triangulation—as anyone knows who’s sat on a threelegged stool—is more stable and—as cartographers know from measurement—is also more accurate. Thus, even three wrong-headed characterizations will endure in their mutual attempt to express reality, although each alone is incomplete and imbalanced. Proof is that this convoluted construction of the Lady, the Witch, and the Immaculate Conception represented the medieval Church view of woman for more than three centuries. THE CHURCH FATHERS T he fault lies with the Roman Catholic Church Fathers for pontificating and perpetuating a repressive characterization of woman. Their statements about women from history and literature reflect a definite prejudice as reflected in the adjectives for woman found in their writings: weak, shallow, garrulous, inferior, temptress, dull-witted, guilty, and sinful.2 Woman for the Church was forever Eve.3 1 2 Herbert W. Richardson, Nun, Witch, Playmate: The Americanization of Sex (Edwin Mellen Press, 1981). St. Paul (?-65 CE), Tetullian (160-225 CE), Origen (185-254 CE), Jerome (347-420 CE), Augustine (354-430 CE), and Ambrose (370-397 CE). S.T. Harty The Lady, the Witch, and the Immaculate Conception Page 2 Eve’s responsibility for the sins of man and the evil in the world was validated for the early Church Fathers through Genesis 3—the old apple in the Garden of Eden myth. Proponents4 for the inferiority of woman during the Middle Ages were well represented by the words of Albertus Magnus who wrote: Woman’s defective nature renders her untrustworthy…beware all women in the way you would a venomous serpent and horned devil. 5 Aquinas blamed woman, as temptress, for the sin of concupiscence—that is, sexual pleasure, specifically when not motivated by maternal ends. The medieval Church bias against woman saw her as lacking in reason, prone to sinful concupiscence, and only good for reproduction. Yet the Middle Ages introduced different economic structures and social relationships, which should have altered the status of women.6 A change in society is usually a catalyst for a change in personal identity and social interaction. If a change is not apparent, then we can expect to find repressive and compensatory forms struggling for expression. What first appeared is an idealized projection that, because of its over-reaching, did not capture the reality of woman. Nevertheless, as C.S. Lewis believed: Real changes in human sentiment are rare, but courtly love was one of them. 7 COURTLY LOVE C ourtly love defines the stylized attitudes and manners that appeared in the poetry of traveling troubadour singers in the Languedoc region of southern France at the beginning of the 12th century. The celebration of sexual love and the poetic conventions that expressed it followed a definite schema. The troubadour sung about a knight who praised a lady and sought her favor through a stylized ritual. Romantic melodramas of battle and noble deeds were the context against which her beauty was displayed. The lady was a paragon of beauty, but her beauty was stylized. Her virtues were more significant. The lady was chaste, loyal, meek, and mild; nevertheless, she was usually the social superior. The song (chanson) of the troubadour concentrated on winning his lady’s “grace.”8 Courtly passion refused physical fulfillment but sustained itself on perpetual longing. The alternating hope and despair of a chase added the drama of excitement and frustration to the troubadour’s art of poetry and song. Of courtliness may boast he who knows how to be moderate…I approve that my Lady should long make me wait and that I should not have from her what she promised me.9 Oddly, the lady of the courtly poem was addressed by the masculine “my lord” (midons). Analyzed linguistically, any relationship to her was a highly conventional version of the feudal relationship between lord and vassal. In other words, the abyss of class separated them. She was the exalted love object, often because she was usually someone else’s wife. When she was not, marriage was not the purpose anyway. Love and the Lady were being honored, not marriage and progeny. Thus, courtly love appears as a flagrant nose-thumbing at the Church’s theology of marriage, which only sanctified union for produce. The Church’s view of marriage perpetuated the inferior position of women in medieval society. Sex, love, 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 Susan Haskins, Mary Magdalen: Myth and Metaphor (New York: Harcourt Brace, 1994). Bernard of Clairvaux (1090-1153), Peter Lombard (1100-1164), Albertus Magnus (1193-1280), and Thomas Aquinas (1225-1274). Albertus Magnus (1193-1280), “De Natura et Origine Animae,” in Opera Omnia, Vol XII, Quaestio 22. Friedrich Heer, The Medieval World: Europe 1100-1350 (New York: New American Library, 1961). C.S. Lewis, The Allegory of Love: A Study in Medieval Tradition (New York: Oxford University Press, 1985). Poetry of William of Poyiers, first troubadour, or Guirant Riguier, the last, also Bertran de Born and Bernard de Ventadour, both from court of Eleanor of Aquitaine, et al., such as Geoffrey Rudel, Peire Vidal, and Guilhelm de Cabestan. Marcabru, a troubadour, in Denis de Rougemont, Love in the Western World (New York: Random House, 1956). S.T. Harty The Lady, the Witch, and the Immaculate Conception Page 3 and woman herself were only justified in marriage The Church’s view of marriage for procreation also reinforced the medieval view of marriage as property contracts. “The Art of Courtly Love” 10 was codified in Latin by a priest and friend of the most respected of the French troubadours, Chretien de Troyes, who wrote “Lancelot.” The most famous troubadour poem is probably “Sir Gawain and the Green Knight.” 11 In fact, a man who did not adore a lady caused doubt in his true knighthood. This idea laid the foundation of courtly chivalry.12 The emphasis in troubadour poetry on love and longing has been considered a popular reaction against asceticism. For example, the Cathars13 in France, Italy, and Spain condemned marriage and required abstinence from those already married. The fidelity and restraint of courtly love also suggested some analogy to divine charity—a yearning that is never satisfied and a gift in grace from the beloved. In courtly love, concupiscence was an indulgence of passion at the expense of reason. 14 One might think that the troubadours were in league with the ladies of the court. If the practice of courtly love had been fully accepted, then women’s position in society might have been elevated from its medieval low. Troubadours were not vying for the ladies themselves. Indeed, some if not most were homosexual artists. They were merely composing and singing the words of love. The ladies of the court were their patrons, not their lovers. The troubadours were furnished with food and lodging at court from the ladies’ hospitality. Surely they would sing for their supper whatever the lady pleased. By the close of the 12th century, the doctrine of courtly love had been thoroughly expounded and well established. Despite regional variations, the idea of courtliness maintained a remarkably stable pattern of behavior and attitudes for the next three centuries. As a peripheral note, one scholar has attested that the game of chess, which originated in India, went through a radical change in Europe in the 12th century.15 Instead of four Kings, which had dominated the game in its first form, a Queen was made to take precedence over all other pieces, save the King. And the one King now was actually reduced to the smallest possibility of real action, even though he remained the final state and consecrated figure, but the Queen could move all over the board. IMMACULATE CONCEPTION C hurch authorities reacted to courtly love by formulating their own concepts of love and woman. Their motive was to redeem courtly love from secular misuse. Bernard of Clairvaux, an ardent devotee of the Virgin Mary, developed the concept of caritas (charity or altruistic love) as an alternative to amor (romantic love) taken from the poets and consecrated in the streams of orthodoxy. A typical clerical counterattack was Bernard’s commentary on the Old Testament “Song of Songs.” He interpreted this romantic language of human passion as an expression of the mystical love of God. In 12th century France, a cult of Mariology emerged as a widespread devotion among ordinary Christians. In fact, monastic orders consecrated monks as “knights of Mary.” Such a title is an obvious clerical response to the secular orders of chivalry under the influence of courtly love. Before this time, the Church had no rites to honor Mary, the Mother of God. The earliest liturgical books of a feast for Mary are from 12th century France.16 This was not the feast of the Immaculate Conception, however. 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 Andreas Capellanus, De Arte Honesti Amandi (1180). Anonymous troubadour, AKA the Pearl Poet (1370). Sidney Painter, French Chivalry, Chivalric Ideas, and Practices in MedievalTimes (Ithaca NY: Cornell University Press, 1957). Denis de Rougemont, Love in the Western World (1940). A.J. Denomy, The Heresy of Courtly Love (New York: Peter Smith Publishing, 1980). de Rougemont. Lyons and Rouen, France (1125). S.T. Harty The Lady, the Witch, and the Immaculate Conception Page 4 Now, I must digress for a moment to clarify what the doctrine of the Immaculate Conception is. Most people think it refers to the Virgin birth. That’s a standard misconception and effectively used in a trivia quiz to separate parochial-schooled Catholics from everyone else. But the Immaculate Conception neither refers to the virginity of Mary nor the conception of Jesus nor the birth of Jesus nor even to the birth of Mary. The doctrine refers to the conception of Mary in the womb of her mother, Anne. Thus, the Immaculate Conception established Mary as the only human being conceived without original sin. By the end of the 12th century, the feast of the Immaculate Conception17 was observed in various cities in England, Spain, and Germany. The Netherlands and Italy followed a century later. Yet Mary’s exemption from original sin took several centuries of doctrinal debates between the Church Fathers. Camps were divided between the Maculists and the Immaculists. Thomas Aquinas, Albertus Magnus, Peter Lombard, and Bernard of Clairvaux—the “greats” of their days—were all against the doctrine of the Immaculate Conception. As Maculist theologians, their strongest advocate was Bernard of Clairvaux, who took the position that Mary was only exempted from original sin at the moment of the Annunciation by the archangel Gabriel.18 Bernard based his objection on the sinfulness of concupiscence, whether progeny resulted or not. Mary was believed to be begotten through the normal sexual act between her father Joachim and her mother Anne. Therefore, Bernard argued, pleasure (libido) entered in, which is sin, and, where sin prevails, the Holy Spirit cannot. Hence, anyone conceived by the concupiscence of their parents could not be exempt from sin. Among the Immaculist theologians, the strongest advocate was Peter Abelard. As a theology professor, Abelard introduced the discussion of the doctrine of Immaculate Conception into Paris schools in 1230, which escalated the doctrinal debates. Abelard championed the position that Mary was both conceived and born without original sin. His view of woman is best understood by his relation-ship to Heloise. Their love letters are proof that Abelard credited virtue and value to the female. In the opinion of most Church Fathers, woman was a temptation to sin and a cohort to the devil. Even in Mary, the purity of her nature was credited to the grace of God. No merit for virtue was conceded to Mary herself. Yet, the Incarnation made Mary’s exemption from the inheritance of Eve essential. The intent of the doctrine of Immaculate Conception was a dialectic resolution of the sin-through-woman theme started with Eve. However, since Mary’s exemption from sin was for being the mother of the Incarnate Christ, virtue for woman was still only deserved through procreation. Paradoxically, Mary’s maternity is linked with its natural antithesis—virginity. The only woman the Church enshrined on high had not so much been exempted from sin as from sex. The Church elevated a model of female virtue—as Virgin and Mother—that was impossible for any woman. During the Middle Ages, critics complained that devotion to Mary was raised to heights of idolatry. Indeed, from the 12th century on, the Virgin Mary generally received the title “Regina Coeli” (Queen of Heaven), which raised Mary (if only metaphorically) to the throne of God, the King of Heaven. Mariology was controversial precisely because it attempted to equalize the sexes in the realm of the supernatural. The titles given the Virgin Mary in litanies to the Immaculate Conception reveal the characterization of woman that was being honored (i.e., maternity, purity, mercy, and love). Never wisdom for the Virgin; that is rational virtue. Thus, Mary became the embodiment of motherly love, purified by virginity as her parents’ concupiscence was purified through divine exemption. The doctrine of Immaculate Conception was the closest the Church could come to understanding woman. She was at best an abstraction consecrated by divine enigma. 17 18 The Immaculate Conception didn’t become Church dogma until 1854 under Pope Pius IX, Ineffalilis Deus, Dec. 8, 1954. Bernard of Clairvaux to the canons of the Cathedral at Lyons, France (1140). S.T. Harty The Lady, the Witch, and the Immaculate Conception Page 5 WITCHCRAFT B elief in witchcraft also developed within a theological framework. In the Hebrew scriptures, Mosaic law had already condemned witchcraft as a crime and proscribed punishment by stoning, which was the same punishment for adultery. In the New Testament, Paul’s Epistle to the Ephesians referenced the character and intentions of the devil. 19 The Book of Revelation describes Eve’s tempter as “that ancient serpent, who is called the Devil and Satan, the deceiver of the whole world.”20 The Church Fathers added this scriptural evidence to their view of woman and the sinful nature of concupiscence. The result was a theological polemic on women as witches in sexual union with the devil. Before the 11th century, most ecclesiastics and theologians considered magic and witchcraft as superstition. The idea of a demonic realm may have gained popular recognition in the Middle Ages precisely because it was an unorthodox position.21 Nevertheless, as belief in witches evolved, these same ecclesiastics and theologians helped formulate and direct popular opinion. All levels of European society were obsessed with witches, and they demanded theological clarification.22 The Church Fathers responded. In the 13th century, witchcraft was prosecuted as a crime, which was specifically assumed as sexual intercourse with the devil. When Aquinas began codifying Christian theology in the 13th century, several of his writings addressed “Magic and Witchcraft,”23 “Demons and Man,”24 as well as “Witchcraft and Sexual Impotence.25” In the latter work, he attested that: The catholic faith…insists that demons do indeed exist and that they may impede sexual intercourse by their works. That Aquinas with his intellectual prowess grants credence to witches is surprising. In his writing on “Witchcraft and Exorcism,”26 Aquinas explained that the witch was a temptation to evil and sin, which is part of our inheritance as God’s creatures and as children of Eve.27 The origin of witches may be ontologically related to diabolic forces in nature, but the characterization of witches and their activities reflects cultural imagination of the times and, therefore, reflects the believers more than the belief. 28 The incantations ascribed to witches were recorded by the Inquisitors from hearsay. Thus, their doubtful accuracy is only the more profitable to analyze for their prejudice. Descriptions of witches are overwrought with gender and sexual bias, reflecting the medieval clergy more than any ontological order of evil. These gender interpretations are supported by medieval woodcuts. The devil, although sometimes an animal, is always anatomically male. A perverted domestic scene is perceived in the witch stirring her boiling cauldron of potions and poisons. The character of a witch must also nullify maternal virtues. Consequently, witches were thought to take children from their parents and sell them to the devil or kill, dismember, and cook the bodies of children. Babies were also taken from the womb by witch midwives. Besides death and illness, the evil that men believed witches inflicted was a catalogue of fears men most dread: impotence, frigidity, and sterility. Natural disasters were also ascribed to witchcraft: hail, 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 Alan Charles Kors and Edward Peters, Witchcraft in Europe 400-1700: A Documentary History (Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 1972). Revelation 12:9. Margaret Alice Murray, The Witch-Cult in Western Europe: A Study in Anthropology (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1921). French witch trails in 13th/14th century list many victims. Italian statutes in 14th/15th century proscribe punishments from banishment to death by fire. Italian witches worked love spells; German witches caused storms and tempests. Aquinas, Summa Contra Gentiles. Aquinas, Summa Theologica. Aquinas, Quod Libet XI. Aquinas, Commentary on the Four Books of Sentences. Monataque. Summers, The History of Witchcraft and Demonology (London: Lyle Stuart, 1979). The manuscript illustrations to Guazzo’s Compendium Maleficarium are particularly illuminating. S.T. Harty The Lady, the Witch, and the Immaculate Conception Page 6 frost, fog, flood, or drought, as well as disease in livestock, rotting crops, shipwrecks, or fires. All the natural evil to which men were subjected because of the Fall was now ascribed to witches. The status of witches as the true daughters of Eve had enlarged impressively. Woman could only be enhanced in a negative aspect. The theological framework for belief in witches held that the agreements binding a witch to Satan were a perversion of the same rites binding a soul to God. Theologians recognized this offense as a heresy, and so witches were brought under the jurisdiction of the Inquisition. This legal connivance protected the Church Fathers in doing their duty against women. The growing belief in witches culminated in a remarkably thorough document on the subject at the end of the 15th century. Two Dominican Inquisitors wrote a handbook about witches, entitled Malleus Maleficarum,29 which laid the foundation for their persecution. Their attitudes on women, witches, and the devil were written in a scholarly style, supported by quotations from Scripture, classical philosophers, and Church authority. The following are excerpts from their chapter entitled: “Why It Is That Women Are Chiefly Addicted To Evil Superstition.” All wickedness is but little to the wickedness of a woman… What else is woman but a foe to friendship, an inescapable punishment, a necessary evil, a natural temptation, a desirable calamity, a domestic danger, a delectable detriment, an evil of nature, painted with fair colors… For it is true that in the Old Testament, the Scriptures have much that is evil to say about woman, and this because of the first temptress, Eve, and her imitators. . . To conclude: All witchcraft comes from carnal lust, which is in women insatiable. Wherefore for the sake of their lust they consort even with devils... It is better called the heresy of witches than of wizards, since the name is taken from the more powerful party. And blessed be the highest who has so far preserved the male sex from so great a crime.30 The witch is persecuted for all the evil, sin, and sexuality that is repressed from the other dominant medieval views of woman: that is, the lady and the Immaculate Conception. Belief in witches attempted to balance the enduring unreality of woman by projecting a negative abstraction against the idealized and spiritualized abstractions. The witch was the new Eve. DENOUEMENT T he mythology of the supernatural always reflects the social construction projecting it. Yet the social and religious spheres in the medieval period of history were particularly entwined. The populace could now assess the injustices of their social order rather than accept the status quo as a divine plan. But the liberation of women was not yet at hand. Instead, we find compensatory characterizations of woman developing within a theological framework, instead of within society. COURTLY LOVE idealized the “lady” on a pedestal of exalted love through highly exaggerated and stylized manners. Romanticized love was the only acknowledged compliment to woman, yet courtly love was a masquerade of romance to becloud the social reality. The need for just compensation sought higher ground, so the Church could sterilize it. The popular devotion to the IMMACULATE CONCEPTION grew out of courtly love in counterbalance. Popular devotion to Mary was an attempt at equality on a 29 30 Heinrich Kramer and James Sprenger, Malleus Maleficarum (The Hammer of Witches, based on writings a century earlier by the Inquisitor, Nicholas Eymericus (1320-1399), 1487), translated by Rev. Montague Summers (1971). Ibid. S.T. Harty The Lady, the Witch, and the Immaculate Conception Page 7 transcendent level. This assertion of supernatural equal rights expressed a repressed unconscious, both social and clerical. The Church had gone through intellectual gymnastics to accept a woman as the mother of God. With woman now idealized and spiritualized, the need for a realistic image still remained. The WITCH became a conceptual deposit of the negative side of these overly exalted views of woman. The Church Fathers had to protect themselves from woman’s sexuality. Belief in witches drew on the familiar antagonism and fear between the sexes and projected them onto a negative abstraction of woman. Woman’s full reality still lay dormant in the medieval mind. This co-dependent syncronicity of the Lady, the Witch, and the Immaculate Conception awaited the liberating consciousness of the feminist movement and modern scholarship to set them free. What is clear is that the Church Fathers needed to go to confession with a new prayer: Bless me, Mother, for I have sinned. © Copyright, Sheila Harty, 1999. Sheila Harty is a published and award-winning writer with a BA and MA in Theology. Her major was in Catholicism, her minor in Islam, and her thesis in scriptural Judaism. Harty employed her theology degrees in the political arena as “applied ethics,” working for 20 years in Washington DC as a public interest policy advocate, including ten years with Ralph Nader. On sabbatical from Nader, she taught “Business Ethics” at University College Cork, Ireland. In DC, she also worked for U.S. Attorney General Ramsey Clark, former U.S. Surgeon General C. Everett Koop, the World Bank, the United Nations University, the Congressional Budget Office, and the American Assn for the Advancement of Science. She was a consultant with the Centre for Applied Studies in International Negotiations in Geneva, the National Adult Education Assn in Dublin, and the International Organization of Consumers Unions in The Hague. Her first book, Hucksters in the Classroom, won the 1980 George Orwell Award for Honesty & Clarity in Public Language. She moved to St. Augustine, Florida, in 1996 to care for her aging parents, where she also works as a freelance writer and editor. She can be reached by phone at 904 / 826-0563 or by e-mail at s t h a r t y @ b e l l s o u t h . n e t . Her website is http:www.sheila-t-harty.com