Secondary Science Teacher Candidates` Practice of Problem

advertisement

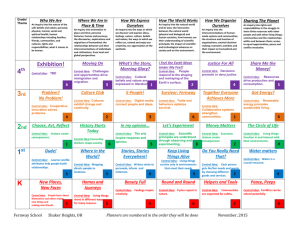

Patterns of Teaching Practice with Respect to Science Content In-Young Cho and Charles W. Anderson, Michigan State University This work was supported in part by grants from the Knowles foundation and the United States Department PT3 Program (Grant Number P342A00193, Yong Zhao, Principal Investigator). The opinions expressed herein do not necessarily reflect the position, policy, or endorsement of the supporting agencies. Keywords: teaching practice, patterns of practice, problems of practice, situated decision, inquiry, problem solving, and teacher education Introduction This is a study of science teachers at the beginning of their careers. We focus on three interns in a five-year teacher education program. Our data come from their intern years, when they were in school classrooms for at least four full days every week. Like other beginning teachers, these interns had to respond to expectations and influences from different communities of practices, and to make curricular decisions on a daily basis. We explored the ways teacher candidates developed their curriculum in actual classrooms as they learned how to teach science content and to develop students’ learning goals. In particular, we focus on how these candidates engaged students in inquiry and taught problem solving to their students. Research questions • What were the candidates’ patterns of practice for teaching scientific inquiry and problem solving? • What factors led the candidates to decide on their patterns of practice? 1 Background Inquiry and problem solving have been extensively discussed in the science education literature, both as methods of science teaching and as goals for science learning. Inquiry pedagogy has been the central theme of National Science Education Standards, yet different conceptualizations of inquiry teaching include various forms of pedagogical practices. The early history of advocating the teaching of science through inquiry argued the importance of engaging students in a process of inquiry. John Dewey placed inquiry at the center of his educational philosophy and emphasized the process of educating reflective thinkers. He stated that science teaching should be dynamic, truly scientific, because the understanding of process is at the heart of scientific attitude (Dewey, 1916/1945). Joseph Schwab (1962) advocated ‘inquiry into inquiry’ as an approach to the teaching of science. Bruner (1962) asserted that students should develop the inquiry skill by cultivating their abilities to formulate and critique their own ideas and theories. In the academic curriculum period of the 1960s, following the Woods Hole conference and typically represented as alphabet soup curriculum, inquiry teaching focused on giving students a better idea of the nature of scientific investigation and the way scientific knowledge is generated. And most importantly, the idea of the science laboratory was put into the essential part of the development of this goal. The basic belief about inquiry of this academic curriculum is the importance of the fundamental rational structure of knowledge, logical relations and criteria for judging claims to truth. In the 1970s, new social concerns such as multicultural education, functional literacy, and humanistic psychology became important issues. Subjective and personal knowledge as objective knowledge that can be tested through reason and empirical evidence attracted more attention. Therefore, the concept of inquiry moved to more subjective, humanistic orientation of knowledge construction. 2 Since ‘Nation at Risk’ (1983), AAAS’s Project 2061 identified desired learning goals, and ‘Science for All Americans’ emphasized nations’ excellence in science, mathematics and technology learning. This envisioned scientific inquiry teaching and learning as the central strategy of science for all students by the NSES (NRC, 1996). During this period, science education studies developed perspective of inquiry in school science teaching as a process that can construe both content understanding and the nature of science. Studies about the role of teachers’ practical knowledge in reform-oriented inquiry teaching (Eick & Dias, 2005; van Driel, Beijaard, & Verloop, 2001; Supovitz, & Turner, 2000; Adams & Krockover, 1997) indicated the importance of direct and explicit exposure to inquiry learning during method courses in teacher education or via professional development programs. Practical knowledge as a constructed knowledge of content and contextualized knowledge of classroom (Munby, Cunningham & Lock, 2000) plays a major role in shaping teachers’ actions in practice and the core of teachers’ professionality (van Driel et al, 2001). Meanwhile, studies on the relation between teacher beliefs, knowledge and practice of inquiry teaching (Wallace & Kang, 2004; Keys & Bryan, 2001; Lumpe, Haney, & Czerniak, 2000; Bryan & Abell 1999; Richardson, 1996) repeatedly reported that teachers’ core belief systems play a central role in teachers’ curricular actions, which mostly preside on the institutional school curricular influences (Munby et al, 2000; Yerrick, Parke, & Nugent, 1997; Tobin & McRobbie, 1996). Inquiry in these studies often suggested a broad definition of inquiry as the incorporation of application into the scientific investigation processes and scientific reasoning skills. This argument was validated by claiming that the broad perspective of inquiry, which includes application and problem solving as well as inquiry as induction of concepts, can be more viable for science classrooms because students can learn both the content and the nature of science through rich applicative processes. Therefore, scientific inquiry often indicated both making inferences and convincing arguments from data, and data analysis as 3 scientific application (Roth, McGinn & Bowen, 1998; Hofstein & Walberg, 1995). Likewise, Inquiry and the National Science Education Standards (NRC, 2000) envision that “inquiry abilities require students to mesh these processes – cognitive abilities and science process skills - and scientific knowledge as they use scientific reasoning and critical thinking to develop their understanding of science” (p. 18). What cognitive abilities means is not explicitly indicated in the document, but if we consider it being distinguished from scientific process skills, it can be understood as constructing and applying scientific knowledge. What we suggest here as inquiry is a method of scientific investigation of the process of scientific knowledge construction. That is, the models/theories which meet the criteria of scientific knowledge suggested by school science curricula based on the knowledge of current professional communities of science. This needs to be distinguished from scientific practice as an application of the scientific knowledge in our conceptual framework for the perspective of inquiry in this study (Anderson, 2003). Similarly, studies of problem solving teaching are informed significantly by the emphasis of process which accompanies content understanding. Windschitl (2004) asserted that current pedagogical discourses in the reform-oriented science education community are more focused on aligning instruction with problem solving and inquiry than content knowledge. Considering the complexities of the situation in which our teacher candidates are located in light of current school science scientific inquiry practices and reform recommendations, Windschtl’s observation should be taken seriously. Teacher candidates’ most often-used teaching practice of scientific inquiry and problem solving comes from their undergraduate years. Moreover, undergraduate science courses focus more on acquiring core classical disciplinary knowledge approved by the current professional scientists’ community than discussions about how new scientific knowledge becomes constructed in the professional scientific community. Candidates also experience tightly controlled laboratory courses during undergraduate years (Trumbell & Kerr, 1993). The implication is that 4 teacher education programs need to provide scientific practice skills such as scientific inquiry and problem solving practices as well as a disciplinary knowledge base by the way of legitimate peripheral participation of apprenticeship (Lave & Wenger, 1991). Literatures contend that two main goals for teaching physical science and chemistry at secondary and tertiary levels are to foster conceptual understanding and problem solving ability. In chemistry and physics education specifically, problem solving is a dominant exercise in the secondary and tertiary classrooms (Champagne & Klopper, 1977; Shuell, 1990; Malony, 1994; Mason, Shell, & Crawley, 1997; Taconis, Ferguson-Hessler, & Broekkamp, 2001). However, early research on problem solving focused on the same issues as science textbooks and teaching practice. Procedures for working with symbols and data were the main component of the practice, which primarily focused on quantitative problem solving procedure. More recent research has focused on the meaning of problem solving procedures to students. The connection between qualitative conceptual understanding and quantitative procedural skills became a critical issue for the teaching problem solving in chemistry and physics classrooms. However, the research shows that many students still acquire procedural skills without conceptual understanding. Traditional problem solving teaching practices rely heavily on exercising a large number of problems so that the instruction is concerned about the sequence of problem solving steps rather than conceptual understanding (Taconis et al., 2001). In addition, typical textbook problems reinforce this tendency by referring to idealized objects and events, which are not connected to the students’ real world experiences. In the 1980s, cognitive processes of problem solving were widely investigated in relation to mental capacity and domain specific or general knowledge (Mayer, 1992). Accordingly, that research focused on the application of those developmental psychological and learning theories into problem solving instruction. In this tradition, research on problem solving was focused on the 5 difference between novice and expert problem solving strategies and the effect of innovative problem solving instruction versus traditional or textbook problem solving instruction. The results showed that novices lack problem solving experiences, problem solving procedures, and an understanding of the domain specific knowledge, all of which are needed in developing solutions to physics problems (Eylon & Lynn, 1988). In the 1990s, researchers focused increasingly on the qualitative meanings that learners saw in quantitative problem-solving procedures. These researchers saw qualitative understanding of quantitative problem solving as a desirable goal for problem solving instruction in science classrooms. Stewart & Hafner (1991) contrasted two viewpoints of practicing science: forward-looking point of view - or “science-in-the-making” in Latour’s (1987) term - and retrospective point of view, or “ready-made-science” according to Latour (1987). They recommended that research should emphasize questions about what students learn from solving problems and how they revise in response to anomalies in data, in addition to questions relating to model using situations. Some research has found that novices learn procedural display without understanding logical principles of the content underlying chemistry and physical science problems (Heyworth, 1999; Mestre, Dufresne, Gerace, Hardiman, & Touger, 1993; Mestre, et al., 1993; Bunce, Gabel, & Samuel, 1991). The complex relation of quantitative problem solving and qualitative understanding is well documented in Huffman’s (1997) study. The finding is that explicit problem solving instruction which address both problem-solving performance and conceptual understanding demonstrated more improvement in the quality and completeness of physics representation, but has no significant difference in students’ logical organization of the solution. Conceptual framework for inquiry and problem solving Our data analysis for understanding teacher candidates’ patterns of teaching practice principally based on the O-P-M model (Observations-PatternsModels) for understanding the nature of scientific knowledge and practice in 6 science teaching for motivation and understanding (Anderson, 2003). First, this framework claims scientific knowledge as three components, “Observations, Patterns, and Models.” Second, scientific practice includes both Inquiry and Application. “Inquiry” in this framework denotes reasoning from evidence and “Application” signifies important uses of models and patterns. Therefore, scientific “Inquiry” has a narrower sense than traditional inquiry literatures which include reasoning from patterns and models. Also, “Application” is used in a broader sense that is not restricted to the quantitative problem solving, but it includes important use of models and patterns, including explaining phenomena and making predictions and so qualitative problem solving. Based on this conceptual framework, we investigated our teacher candidate’s patterns of teaching practice for science content teaching and students’ learning goals. The unit of analysis was inquiry and problem solving teachings. In the analytical process, we developed a general problem solving model which includes all three case studies from the previous year’s paper. Observations-Patterns-Models model Explaining scientific knowledge and practice in reform-based science teaching and learning, Anderson (2003) depicted three components of scientific knowledge as the tool of making sense of the material world: a) experiences in the material world, b) patterns in experience, and c) explanations of patterns in experience. Each corresponds to Observations, Patterns, and Models in a new model for initial framework in Teaching Science for Motivation and Understanding. In thinking about scientific knowledge, it is essential for candidates to understand the key experiences, patterns and explanations relevant to the topics that they taught, and to distinguish among them. In thinking about scientific practices, scientific inquiry and application are essential and the most fundamental kinds of scientific practices that candidates need to know and apply. National standards documents emphasize enhancing students’ scientific thinking skills by means of scientific inquiry teaching and learning. The content standards are statements of patterns in observations or models that scientists 7 use to explain those patterns — the two right-hand ovals in Figure 1. However, those patterns and models are always based on specific observations — the lefthand oval. The arrows indicate that assessing understanding of patterns often involves asking students to relate them to specific observations, as when we assess understanding of the benchmark about plants’ need for water and light by asking students to predict what would happen to bean plants grown under different circumstances. The ovals in Figure 1. also indicate a variety of synonyms for the Observations, Patterns, and Models. The rich vocabulary that scientists and science educators use to make these distinctions indicates how important they are in both science and science education. There are also some commonly used terms that are not included or used with restricted meanings: “Fact” are not found anywhere in this framework. Observations, patterns, and models are all sometimes referred to as facts. “Concepts” is another missing term. Again, this term is used with many meanings in science education, usually referring to either patterns or models. “Skills” are also missing. The arrows connecting the ovals could be labeled as skills, but that decision is complicated. More on this in the notes on Chapter Four. “Hypotheses” are listed in the Models oval as tentative models or theories. However, specific predictions based on tentatively held models are also sometimes called hypotheses (e.g., “the null hypotheses.”)] “Inquiry” is used in this figure in narrower sense than is typical in science education. Science educators often use inquiry to denote the entire process of conducting scientific investigations, which includes both reasoning from evidence and reasoning from models and patterns. In this figure inquiry is restricted to reasoning from evidence. Some educators also use a narrower definition of inquiry, suggesting that all scientific inquiry takes the form of experiments with independent variables, dependent variables, controls, etc. 8 “Application” is used in this figure in a broader sense than is typical in science education. Science educators often use application to denote practical problem solving and/or engineering design. In this figure, application also includes other important uses of models and patterns, including explaining phenomena and making predictions (e.g., quantitative or qualitative problem solving) Reasoning from evidence (Inquiry): Finding patterns in observations and constructing explanations for those patterns Observations (experiences, data, phenomena, systems and events in the world) Patterns in observations (generalizations, laws, graphs, tables, formulas) Models (hypotheses, models, theories) Reasoning from models and patterns (Application): Using scientific patterns and models to describe, explain, predict and design Fig.1. Scientific knowledge and practices (Anderson, 2003) Problem Solving Model for Content Understanding Considering problem solving as one form of scientific practice, we derived the general model of problem solving process from connected knowledge of experience, patterns, and explanations in dealing with data, variables and equations. In reform-oriented science teaching, data analysis is a key step in scientific inquiry and problem solving is a key form of scientific application, whereas procedural display, which follows procedures in a linear order, is a prototype of problem solving in traditional school science teaching. The key issue is the meaning attached to variables, data tables, and equations: Are they ways of describing experience and summarizing patterns or are they symbols to manipulate and procedures to follow? 9 To understand qualitative meaning-making science teaching practice in quantitative problem solving procedure and data analysis problems of practice, we propose the problem solving model. Then, we inquire what makes the difference in the problem solving model for each candidate in terms of situated decisions in the advancement of learning to teach. We try to adduce teacher candidates’ development of professional identity among the influences of the complex interactions between different professional learning communities. To generate a scientific problem solving model, the data, represented by numeric and physical parameters, which extracted from experience of material world to infer patterns and explanations of it, is used to depict variables in equations, which are representations of scientific principles and laws. Typically, textbook problems in physical science refer to idealized objects and events which fit to sets of idealized variables and equations. In solving such idealized problems, before mathematical manipulation of equations begin, problem solvers must decide a) which scientific variables would be useful to answer the question, b) what concepts and principles could be applied to determine those variables. That is, the problem solving process is composed of allocations of data from experience/real world examples and phenomena and extractions of variables from data which can be put into equations, which represent what patterns/scientific laws and principles are to be applied in explaining the scientific theories and models (Fig. 2). 10 Problem Solving Model Inquiry Application Data Analysis Experience School science: Data analysis and problem solving are isolated procedures Data Patterns Represented by Variables Equations Explanations Reform science teaching: Data analysis and problem solving are seen as part of larger processes of inquiry and application Problem Solving Figure 2. General model of problem solving Conceptual framework for candidates’ teaching practices Teaching practices and problems of practice Trying to understand and describe teachers’ patterns of practice is a complex business, particularly since teachers’ practices are based largely on experience or what van Driel, Beijjard, and Verloop (2001) describe as practical knowledge. Practical knowledge tends to be action-oriented, person- and context-bound, tacit, integrated, and based on beliefs. We chose a teaching practice as the unit of analysis deduced from Wertsch’s (1991) writing about mediated action as a unit of analysis, and from activity theory (Engeström, 1999). We used the term practice rather than activity for a couple of reasons. First, it avoids confusion with another common usage for activity: learning activities in 11 classrooms. Second, the term practice connotes repeated or habitual action, which is consistent with our intended meaning. Building a pattern of teaching practice involves developing responses to the four fundamental problems of practice which are composed of individual practices as shown in Figure 3. This study analyzed teacher candidates’ learning around the problems of practice: relearning science content and developing goals for students’ content understanding. The four problems of practices are as follows: (Anderson 2003) Relearning science content and developing goals for students’ content understanding. Understanding students and assessing their learning. Developing classroom environments and teaching strategies. Professional resources and relationships. Patterns of practice Problems of practice -science content and learning goals -students and assessment -classroom management and teaching strategies -professional resources and relationships Individual practices (e.g. grading, managing class discussions, teaching problem solving) Figure 3. A hierarchy of teaching practices Situated curricular decisions 12 Our understanding of the candidates’ decisions has been influenced by Smith’s (1996) writing about efficacy and telling in mathematics teaching. Following Smith, it appears to us that school science persists partly because it offers a belief system and a set of practices that allow teachers and students to achieve a sense of personal efficacy and success in their assigned roles. Reform science teaching, as exemplified by expert practitioners like Jim Minstrell (1984) or Barbara Neureither (Richmond & Neureither, 1998) offers an alternate belief system and practices that allow teachers and students to feel efficacious. Candidates need to respond to two interlocking challenges during intern years. The first is learning to do the work of science teaching. They were expected to deal with the multiple demands of being a full-time science teacher for the first time. The second challenge was making curricular decisions. They needed to make choices about priorities, about mentors, and about how they will present themselves as science teachers. As they do, they develop a coherent set of narratives about their present practice and their future aspirations. These challenges were difficult because the candidates were situated as legitimate peripheral participants in three different communities of practice: a) professional community of science educators who deliberately advocate reformoriented science teaching and learning b) professional communities of teaching and school administrative staffs and c) communities of parents and students. The candidates’ decisions about how they would engage each community were affected by their own norms and values, the kinds of practice that were encouraged in their school placements, and many other factors. Thus, we describe these choices as situated curricular decisions - decisions that were often made subconsciously and were affected both by candidates’ knowledge and values and their teaching situations. Method 13 The observations, recordings, and field notes in this study were taken in completely naturalistic settings. The research method is based on hermeneutical/interpretive method using multiple data collection, triangulation, constant comparative analysis, and inductive abstraction by coding and categorization (Glaser & Strauss, 1967; Hutchinson, 1988). This method aims at discovering and communicating the meaning-perspectives of the participant teacher candidates by identifying specific structures of occurrences, rather than overall distribution, and observing the meaning-perspectives of the particular actors in the particular events. Second, we tried to gain specific understandings of concrete details and local meanings of each candidate’s teaching practice and compare and contrast them to distinguish/identify the context/factors shaping those particular practices and knowledge of science teaching related to the activities of specific candidates in making decisions and conducting curricular action. This study seeks to understand and to discover the specific ways in which teacher candidates develop their practical knowledge and practice, fundamental to the curricular decisions and actions throughout interactions with other agents as well as their own beliefs and values within school contexts and culture. The data reported were collected during the participants’ intern years. Data collection began with candidates’ class assignments including lesson and unit plans, teaching investigation and inquiry cycles. We filmed for the lead teaching and took observational field notes. Also, semi-structured interviews with candidates, mentor teachers, and field instructors were taken after class observations. In considering their viewpoint of science teaching we referred to philosophy statements submitted by teacher candidates. Participants The profiles of three teacher candidates in this study are as follows. Lisa Barab: Lisa entered the program as an honors student with a near4.0 grade point average in chemistry. She had a major in chemistry and a minor 14 in mathematics. She was an intense, lively student who had a close relationship with her father, also a chemist. She taught chemistry and mathematics in a suburban high school. John Duncan: John was a quiet, thoughtful man who was changing careers. He had spent six years as a civil and environmental engineer before entering the program. He had a major in physical science and a minor in mathematics. Working in a suburban ninth-grade physical and earth science class, he basically adopted his mentor teacher’s classroom curriculum and activities. Mike Barker: Mike was a chemistry major and mathematics minor. Like John, Mike was changing careers. He came to the program after a successful 16-year career as an industrial chemical engineer and manager. Although his perspective differed from the program’s, Mike was a well organized and effective classroom teacher in an urban high school, earning the trust of his mentor and keeping his students on task in well-paced classes. He taught chemistry and mathematics. Results One of the observations is that teacher candidates’ understanding of scientific inquiry and the process of problem solving does not necessarily reflect the nature of science and the reform recommendation of inquiry based science teaching and learning. They develop their own patterns of teaching practice of inquiry and problem-solving while learning about those practices from different communities. They needed to decide what the most desirable practice in their situation was out of the complexity of teaching practices (Labaree, 2000). Lisa The topic Lisa taught was kinetic molecular theory of gases, and the observed lesson unit was the combined gas law. The general participation structure of her classroom was based on interactive and cooperative discursive 15 relations between peers and also between teacher and students. Desks were set up as groups, and students were encouraged to participate in small group cooperative tasks. Most of the time, they actively discussed and tried to complete their tasks either in quiz or lab sessions. Lisa was the candidate who actively searched for ways to enact reform-oriented science teaching. She negotiated meanings with students through divergent questioning and case-specific coaching. Her questioning, “What do we need to know?”, made students take responsibility and authority of their thinking and knowledge acquisition. As she advocated her teaching philosophy, she aspired to teach scientific inquiry both in thinking and process skills, and most importantly, based on students’ own experiences. She developed and used teaching materials which can connect experientially real phenomena to the chemistry problems or any activities in chemistry class, because chemistry is all around our actual living world. She always kept a co-inquirer attitude and did not directly give answers to students’ questions, but made them recall possible explanations by connecting real world experiences and previous lessons. Assignments or worksheet problems stated real world phenomena, not just numerical data. She was willing to take time for exploration of the phenomena and withdraw students’ own thinking process in solving problems or discussions about lab activities. Overall, her teaching was based on model-based reasoning focused on inductive and causal reasoning starting from exploring Observations/Experiences, to finding Patterns and to Models/Explanations. Following is the summary of her teaching practice. Inquiry teaching The title of Lisa’s inquiry cycle was “the determination of Boyle’s law from demonstrations.” The inquiry cycle was formulated by four major sequences of activities: a) questions: communications, b) evidence: data and patterns, c) students’ explanations, and d) scientific theories or models. Lisa initiated the discussion about gaseous pressure by asking questions related to atmospheric 16 pressure differences experienced by students. The specific examples she used in drawing questions from students’ experience are as follows: ‘your weight at sea level versus a very high altitude’, ‘your ears popping in a plane’, ‘your ears popping in the deep water.’ Lisa had three demonstrations: Balloon in vacuum bell jar, marshmallow in vacuum bell jar, and shaving cream in vacuum bell jar. In each case, the inflated balloon, marshmallow, and shaving cream in the jar increased in volume. This happened because of the pressure decrease when the vacuum pump was turned on to draw out the air and decrease the pressure in the jar. For these demonstrations, Lisa put emphasis on posing questions which can lead to students’ prediction. Students were required to record their predictions in their notes. Lisa started scientific inquiry from experience inductively and tried to induce students’ effort to finding patterns in the data from divergent questioning, demonstrations, and open discussion. Lisa was utilizing experientially real data that students can access empirically from their daily life and from demonstrations. She used experientially real questions and demonstrations to expound how to predict the relation between air pressure and volume in different materials and phenomena. Lisa wanted to “have the students observe and record what happens in the various demonstrations. They will record their observations, data, and make drawings in their notebook. The teacher will perform the demonstrations in front of the class so all can see. The teacher may even ask students to come closer, draw pictures, to make better observations.” Lisa’s strategy for finding patterns from experience was using guiding questions which lead to discussions that can connect three demonstrations into one general explanation. She mentioned about facilitating students’ explanations about their own activities, “Have the students explain what happened in the demonstration by using drawings as well as words.” And part of the class time was allocated to discuss and write or draw students’ own explanations about their observations. Lisa expressed her intention as “Students will be given time in class to do this, as well as time to talk with one another and discuss their 17 ideas.” Lisa described how to lead students towards finding patterns by connecting three demonstrations together. She used guiding questions for this purpose such as “what remained constant in the three demonstrations? What variables changed? What are the similarities among the demonstrations? Did they alter in the same way? etc.” Another noteworthy explanation about the teacher role in facilitating scientific inquiry process was “For the most part, I will let them work together and struggle. The questions will be asked depending on how they do.” This shows how she emphasizes students’ own sense-making in finding patterns to understand the phenomena they observed and discussed. Lisa’s approach of scientific inquiry represented model-based reasoning from evidence derived from experientially real data as described above. And the teacher is a co-inquirer who wants to scaffold students’ active sense-making and reasoning for scientific inquiry. Observations (experiences, data, phenomena, systems and events in the world) Patterns in observations (generalizatio ns, laws, graphs, tables, formulas) Models (hypotheses, models, theories) Figure 4. Lisa’s inquiry teaching Problem solving teaching When she was teaching solving combined gas law problems, Lisa worked to connect students’ understanding and her goals for students’ learning. Therefore, scientific knowledge as Explanations/Theories was not an isolated entity from students’ own explanations and understanding. Even when she didn’t ask the chemical impact of the change of physical variables, she treated problem-solving procedure as how we represent chemical ideas with numbers 18 and physical units and how the relationship between variables are represented in the questionnaires. Students’ understanding of chemical principles behind chemical equations and using patterns and explanations in experiences to find relationships among variables in the chemical equation was a critical factor for her teaching. She also emphasized understanding of the meanings of chemical equations and appropriate manipulation of physical parameters and chemical conditions. For example, she explained the conditional difference between two temperature (T), volume (V), and pressure (P) sets with the principles of ideal gas law in a molecular theory by collision theory and molecular speed of gases. Lisa was acute to students’ prior knowledge base and she carefully guided how to understand the questionnaire itself first. For example, Lisa coached students to use dimensional analysis and algebraic skills to manipulate temperature, pressure, volume, and number of moles of gases correctly. Lisa treated the problem solving procedure as how we represent chemical ideas with numbers and units and how the relationship of the parameters is denoted in equations. Lisa’s problem solving teaching as science application was not separated from scientific inquiry process. Lisa was determined to teach scientific inquiry as a way of scientific practice to obtain scientific understanding of the core concepts of the discipline. She always tried to induce students’ critical thinking about what theories and laws are underlying behind the equations. Students were highly encouraged to participate in those discussions. She wanted students to see the real world experiences as the scientific phenomena and thus exemplified how to extract data from the experiences and how to put those data into the variables in appropriate equations. For example, when a student showing the solution of a gas law problem on her worksheet asked why the pressure goes so big when the volume changed in a constant temperature, Lisa gave an example. She explained that when we push one end of a syringe in room temperature, of which the other end is sealed with cork, you can feel the pressure of the air between the cylinder and the cork and she explained about the collision theory. Also, she tried to show how we can combine quantitative and qualitative data analysis to 19 gain sound conceptual understanding. Her aim of teaching science for conceptual understanding and using scientific inquiry as a tool for it made her practice closer to excellent science teaching even though sometimes the whole process could not be enacted as she intended. Experience Data Patterns Explanati ons Represented by by Variables Equations Figure 5. Lisa’s problem solving model John John’s teaching involved lots of information technical skills such as all students’ individual use of wireless internet, power point presentations, demonstration lab kits, and OHP. His classroom was full of visual and technological representations, teacher explanations, and discussions mainly between teacher and students. Consequently, important instructional strategies included using technical resources to find useful data sets or activities. The topic he taught, ‘Regional and Global Climate Patterns, Seasonal climate change’ actually required global and regional data sets that could not directly be obtained from students’ own activity. Compared to teacher-student interactions, time spent in peer discussions was not significant, and desks were arranged toward whiteboard in a row. Usually, class started with a review of previous lessons followed by collecting assignments. Teacher-directed explanations accompanied 20 by questioning and students’ short answers were typical for the whole class lecture time. In a small demonstrative lab and problem-solving with worksheets sessions, John didn’t organize the class as small group cooperative stations and did not inquire students’ scientific ideas or their own theories and the reasoning processes. Scientific knowledge was a declaration established by thorough scientific processes by professional scientists and students needed to learn about those key concepts and scientific reasoning skills. John selected and adapted class activities through extensive information technology skills and thoughtful consideration of curriculum development according to the science standards, expectations from mentor teacher and school setting, and also learning from teacher educators how to teach reformbased science for content understanding. Inquiry teaching John’s inquiry cycle was planned for “Regional and Global Climate Patterns, Seasonal climate change.” In the introduction, John used a demonstration with a flashlight to show the relation between the angle of light and the amount of energy transferred from the Sun to the Earth. Students were asked to think about the questions provided. Data and experience were given as an assignment in which students visit the U. S. Naval Observatory website and complete three data tables for the length of the day and maximum altitude in three different cities in U.S. for four seasons. Also, it contained questions about the relationship between the length of the day and altitude of the sun and season. Besides, more questions asked weather patterns for different cities and the reason for that. John expected students to find Patterns in data packet and the assignment activity which required students’ explanations. “Students will be given the attached assignment. In it, they will be reviewing data and then formulating explanations.” And he explained how the teacher will help students’ inquiry learning for finding scientific theories and Models/Explanations. “The teacher will 21 review with the students appropriate theories and models to explain the Earth/Sun relationship and more thoroughly address the questions presented in the introductory period.” For this inquiry cycle, John was concerned about students’ experience, “One thing that was problematic was they had difficulty visualizing the length of day”. He developed PowerPoint presentations for the explanations of this inquiry cycle and they helped visualization of the weather phenomena and effectively captivated students’ attention. Overall, his inquiry cycle reflected his inductive approach from Observations/Experience to Patterns and Explanations and he demanded students’ active engagement and generation of their own Models/Theories for the Patterns in data packet. However, when he taught “Prevailing wind” by creating “wind rose diagram”, conducted as a small lab activity, John spent most of the time to give detailed directions of drawing the diagram with whole class demonstration and specific indications of how to extract Patterns in data set. The participation structure was inclined to the teacher’s well-organized sequential presentation of concepts with scientific reasoning skills about how to conceptualize scientific Models/Theories and with elaborated instructional directions. There was not enough evidence if students negotiated their ideas and meanings with presented scientific ideas and if they could connect current concepts to previous lessons about the relation between the air mass movements and wind speed. Observations (experiences, data, phenomena, systems and events in the world) Patterns in observations (generalizatio ns, laws, graphs, tables, formulas) Models (hypotheses, models, theories) Figure 6. John’s inquiry teaching 22 Problem solving teaching The topic John taught was “describing weather, winds, fronts, and storms” and the major task of the lesson was reviewing chapter exercise problems. John had a whole class lecture session with the problem reviews, which basically require conceptual knowledge of air mass movement and weather patterns. A major strategy of demonstrative problem-solving was organizing scientific information of the topic with diagrams and tables and by explaining the conceptual network of the topic. He tried to organize the specific individual weather reports suggested in the textbook problems into Patterns in the EPE framework so that students can understand the relations between concepts. Then occasionally he gave some Models/Theories about the weather patterns and air mass movement but they were restricted to local explanations of air pressure difference and air mass difference not extended to other atmospheric factors such as heat energy, cycling of water in and out of the atmosphere, etc. The concepts he employed were air mass, air pressure, wind, front, clouds, wind direction, weather, and extreme weather according to the questionnaires in the textbook. For general explanations about the relations between fronts, clouds, and weather patterns, John distributed ‘side views of fronts that move through Michigan in a west to east pattern’ diagram and employed questioning and answering method to explain the pattern; where cool air mass and warm air mass were located and how they moved, what was the shape of the fronts, what kind of clouds were formed, and what weather phenomena could be observed in what regions. His problem solving teaching focused on finding a good data set that shows particular earth science phenomena, extracting specific patterns from the data, and using variables to explain how those patterns are represented by variables. 23 Experien ces Data Patterns Explanati ons Represented by Variables Equations Figure 7. John’s problem solving model Mike The topics Mike taught were thermodynamics and reaction kinetics. The observed lesson unit included Hess’s Law and Le Chatelier’s Law. Mike thought he did not have enough time to do labs in order to affirm the scientific knowledge, as a body of knowledge to be learned and established by a community of professional scientists. In a typical lesson students completed a worksheet, and Mike went over the answers. He liked to prepare students for various tests. Thus, the learning environment he tried to maintain in his classroom facilitated this transfer of knowledge; the desks were neatly in rows facing Mike and the board. His lectures focused on the definitions of basic terms and demonstrating algorithmic processes for problem solving. His quizzes assessed if students could define terms exactly the same as Mike taught them and follow the procedural skills that they learned. Assignments for the same purpose were given to students. In the post observation interview, he showed how he gave scores for the quizzes and tests in his class: “One of the challenges that teachers face is creating an assessment that is a good measure of how much their students have learned and how much they know.” Mike tried to keep students 24 quiet and working all during the class period to ensure that all students could learn the science knowledge efficiently. Mike said that his primary resources for lesson planning were the textbook and mentor teacher’s notes. He carefully sorted them to find important topics for each unit and liked to find more problems to give students more opportunity to exercise problem solving procedures to prepare for tests. Inquiry teaching In the first draft of his Gas Law inquiry cycle, Mike described a process where he gives students the Gas Laws before demonstration for students’ Observations. The first stage of his essential features of classroom inquiry, ‘evidence: data and patterns’, was planned to make students answer the questions given along with the definition of basic terms and gas laws. His inquiry plan described, “Learner gives priority to evidence in responding to questions. Basic vocabulary and conversion factors are given to the students along with three gas laws (Boyle’s, Charles and Gay-Lussac’s).” This deductive approach of scientific inquiry reflected Mike’s priority of science content teaching and students’ learning goals: application of theories and correct use of problemsolving procedures. According to Mike, school science does not allow in-depth inquiry unlike scientist’s science so that the scientific inquiry cycle as Observations-Patterns-Models cannot be practically exercised in school science classrooms. In his revised “Inquiry cycle” assignment, one of the essential features of classroom inquiry he identified was ‘cooperative work with peer students.’ However, it happened as a way of examining the other students’ answers to the problems in the worksheet if it is correct or not. And it was not a form of students’ active involvement in discussing how they reach the result or what they think each of the process and connecting associated phenomena from their real world experience. Students were asked to know about the mechanism of how textbook 25 scientific knowledge works in high school chemistry and how to obtain the skills for obtaining right answers. Observations (experiences, data, phenomena, systems and events in the world) Patterns in observations (generalizatio ns, laws, graphs, tables, formulas) Models (hypotheses, models, theories) Figure 8. Mike’s inquiry teaching Problem solving teaching Mike focused on the algorithmic principle and mathematical skills for solving thermodynamic chemical problems to obtain right answers and mastery of scientific terms. Making science accessible to students was his main purpose. He treated the variables in chemical equations as symbols to be manipulated correctly. The introductory part of his lesson was often a recall of vocabulary. Then, he reminded students of some procedures to use in chemical equations to obtain right answers in problem solving. For example, he introduced the term enthalpy change in terms of how to calculate the overall enthalpy change for the chemical reaction. Mike conducted several of these demonstrations for Hess’s Law problems. He skipped discussions about the real merits of this mathematical process of calculating enthalpies. He explained enthalpy of reaction without explaining or drawing enthalpy diagrams. Mike treated the exothermic reaction and endothermic reaction as if they were characterized as the signs of enthalpy of reaction, ΔH. He said that if the sign was negative, the reaction was exothermic, and if the sign was positive, the reaction was endothermic. Mike emphasized detecting variables which can provide clues about how to get the answer and taught how to put those variables into chemical equations. 26 His explanations about the algorithms to apply to the equations from given variables often did not include what chemical principles and laws are represented by the equations. His intention to teach algorithms for the key element of problem solving resulted from his instructional objectives. He believed that through successful experiences of dealing chemical equations with mathematical tools and variables, students can achieve an understanding of scientific terms and basic concepts. Experience Data Patterns Explanati ons Represented by Variables Equations Figure 9. Mike's problem solving model Discussion All three candidates were among the best this program should offer. They were thoughtful, informative both intelligently and technologically and most of all they held strong aspirations for being an effective science teacher. They made their situated decisions in the context of the expectations and influences of professional communities of practice. The factors that affected their situated curricular decisions included the professional communities of practice in their 27 schools, their content understanding, and their beliefs about the role of school science and science teaching. School professional community of practice One prominent influence was the expectations and demands from their school professional communities of practice. Lisa taught an elective chemistry class in suburban high school and her mentor teacher shared reform-based science teaching idea and supported finding resources and planning classroom activities. They also had co-planning meetings with other chemistry teachers regularly. John was teaching earth science, which was neither his major nor minor, in a suburban high school. He was coping with his mentor teacher’s extensive curriculum coverage and didactic teaching style. He developed a significant amount of curriculum materials using visual and information technology skills. Mike taught a lower-track class in an urban high school. His mentor teacher had an agreement in teaching priorities with him and had the same chemistry learning background as a chemical engineer. Content understanding Candidates’ depth of understanding and ways of thinking about the content that they taught were different. Lisa came closest to the view of science advocated by the reform documents. She saw chemistry as providing a set of intellectual tools for making sense of the material world and changes in it. Mike’s understanding of chemistry was process-oriented; he had 15 years’ experience working as a chemical engineer. He viewed school science content as the “hard core” assumptions that differentiate right and wrong answers to problem solving practice within a “research program” (Lakatos, 1970). Also, it had been a long time since he had studied the specific topics that he was expected to teach in the high school curriculum, and he was more inclined to see chemistry as providing utilitarian tools for practical problem solving. John, who was teaching out of his 28 field, was more prone to see science as consisting of canonical facts and procedures to be reproduced by their students. Beliefs about school science and science teaching Lisa believed school science can be a practice of scientific method to construct active science knowledge building. With this strong constructivist belief of science learning and teaching, she encouraged students to actively engage in scientific sense-making. Lisa saw chemistry as intrinsically interesting, and she wanted her students to share her interest and understanding of chemistry as a way of making sense of the material world. John shared Lisa’s focus on science as a way of making sense of the world, but his approach was more formal and less intuitive than Lisa’s. In part because he was teaching earth science, he relied more on archived data sets and less on direct experience than Lisa did. He also emphasized the importance of having students master correct procedures for data analysis and problem solving. He wanted his students to find patterns in data, but he exerted careful control over both the data and the pattern-finding processes. Mike saw chemistry as intrinsically useful, and he wanted his students to learn how to use the tools that it provided. He saw school as a place where students would learn the skills that they needed in work and in life, and he saw chemistry as a place to learn those skills. He was especially concerned with the mathematical skills that students need for correct problem solving. References Abd El-Khalick, F., BouJaoude, S., Duschl, R., Lederman, N. G., Mamlok-Naaman, R., Hofstein, A, Niaz, M., Treagust, D., & Tuan, H. (2004). Inquiry in science education: International perspectives. Science Education, 88, 397-419. 29 Adams, P. E. & Krockover, G. H. (1997). Concerns and perceptions of beginning secondary science and mathematics teachers. Science Education, 81, 29-50. Anderson, C. W. (2003). Teaching science for motivation and understanding. East Lansing, MI: Michigan State University. (http://scires.educ.msu.edu/Science05/public/te802/TE802Readings.html). Brown, J. S., Collins, A., & Duguid, P. (1989). Situated Cognition and the culture of learning. Educational Researcher, January-February, 32-41. Bruner, J. S. (1962). On knowing: Essays for the left hand. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press. Bryan, L. & Abell, S. K. (1999). The development of professional knowledge in learning to teach elementary science. Journal of Research in Science Teaching, 36, 121139. Bunce, D. M., Gabel, D. L., & Samuel, J. V. (1991). Enhancing chemistry problemsolving achievement using problem categorization. Journal of Research in Science Teaching, 28(6), 505-521. Champagne, A. B., and Klopper, L. E. (1977). A sixty-year perspective on three issues in science education: I. Whose ideas are dominant? II. Representation of women. III. Reflective thinking and problem solving. Science Education, 61(4), 431-452. Collins, A., Brown, J. S., & Newman, S. E. ( 1989). Cognitive apprenticeship: Teaching the craft of reading, writing, and mathematics. In L. B. Resnick(Ed.), Knowing, Learning and Instruction: Essays in honor of Robert Glaser. Hillsdale, NJ: Erlbaum. Crawford, B. A., Krajcik, J. S., & Marx, R. W. (1999). Elements of a community of learners in a middle school science classroom. Science Education, 83, 701-723. Dewey, J. (1916/1945). Method in science teaching. Science Education, 1, 3-9. Reprinted with a new introduction by the author (1945) Science Education, 29, 119-123. Doyle, W. (1984). Academic work. Review of Educational Research, 53(2), 159-200. Eick, C. & Dias, M. (2005). Building the authority of exereince in communities of practice: The development of preservice teachers' practical knowledge through coteaching in inquiry classrooms. Science Education, 89, 470-491. 30 Engeström, Y. (1999). Activity theory and individual and social transformation. In Y Engeström, R Miettinen, & R-L Punamäki (Eds.). Perspectives on activity theory. Cambridge: Cambride University Press. Pp. 19-38. Eylon, B., & Linn, M.C. (1988). Learning and instruction: an examination of four research perspectives in science education. Review of Educational Research, 58, 251-301. Glaser, B. G. & Strauss, A. L. (1967). The discovery of grounded theory: Strategies for qualitative research. New York: Aladin Publishing Company. Hashweh, M. Z. (1996). Effects of science teachers' epistemological beliefs in teaching. Journal of Research in Science Teaching, 33, 47-63. Heyworth, R. M. (1999). Procedural and conceptual knowledge of expert and novice students for the solving of a basic problem in chemistry. International Journal of Science Education, 21(2). 195-211. Hofstein, A., & Walberg, H. J. (1995). Instructional strategies. In B. J. Fraser, & H. J. Walberg (Eds.), Improving science education: An international perspective (pp. 120). Chicago, IL: Chicago University Press. Huffman, D. (1997). Effect of explicit problem solving instruction in high school students' problem-solving performance and conceptual understanding of physics. Journal of Research in Science Teaching, 34 (6), 551-570. Hutchinson, S. A. (1988). Education and grounded theory. In Eds. Robert R. Sherman, & Rodman B. Webb. Qualitative Research in Education: Focus and Methods. Explorations in Ethnography Series: The Falmer Press, London, 123-140. Keys, C. W. & Bryan, L. A. (2001). Co-Constructing inquiry-based science with teachers: Essential research for lasting reform. Journal of Research in Science Teaching, 38(6), 631-645. Labaree, D. F. (2000). On the nature of teaching and teacher education: Difficult practices that looks easy. Journal of Teacher Education, 51(3), 228-233. Lakatos, I. (1970). Falsification and the methodology of scientific research programs. In I. Lakatos & A. Musgrave (Eds.). Criticism and the Growth of Knowledge. New York: Cambridge University Press, pp. 91-195. Lave, J. & Wenger, E. (1991). Situated learning: legitimate peripheral participation. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. 31 Lumpe, A. T., Haney, J. J., & Czerniak, C. M. (2000). Assessing teachers' beliefs about their science teaching context. Journal of Research in Science Teaching, 37(3), 275-292. Malony, D. P. (1994). Research on problem solving: Physics. In D. Gabel (Ed.), Handbook of research on science teaching and learning. Washington DC: National Science Teachers Association. Mason, D. S., Shell, D. F., and Crawley, F. E. (1997). Differences in problem solving by nonscience majors in introductory chemistry on paired algorithmic-conceptual problems. Journal of Research in Science Teaching, 34(9), 905-923. Mayer, R. E. (1992). Thinking, problem solving, cognition (2nd Ed.). New York: W. H. Freeman and Company. Mestre, J. P., Dufresne, R. J., Gerace, W. J., Hardiman, P. T., & Touger, J. S. (1993). Promoting skilled problem-solving behavior among beginning physics students. Journal of Research in Science Teaching, 30(3), 303-317. Minstrell, J. (1984). Teaching for the development of understanding of ideas: Forces on moving objects. In C. W. Anderson (Ed.), Observing science classrooms: Perspectives from research and practice (1984 yearbook of the Association for the Education of Teachers in Science, pp. 55-73). Columbus, OH: ERIC Center for Science, Mathematics and Environmental Education. Munby, H., Cunningham, M., & Lock, C. (2000). School Science Culture: A case study of barriers to developing professional knowledge. Science Education, 84, 193-211. National Commission on Excellence in Education (1983). A Nation at Risk: the Imperative for Educational Reform. Washington, D.C.: U.S. Department of Education. National Science Research Council. (1996). National Science Education Standards. Washington, DC: National Academy Press. National Science Research Council. (2000). Inquiry and the National Science Education Standards. Washington, DC: National Academy Press. Richardson, V. (1996). The role of attitudes and beliefs in learning to teach. In Sikula (Ed.), Handbook of research on teacher education. (pp. 57-64). Hillsdale, NJ: Erlbaum. Richmond, G. & Nuereither, B. (1998). Making a case for cases, American Biology Teacher, 60 (5), 335-342. 32 Rogoff, B. (1990). Apprenticeship in thinking: Cognitive deelopment in social context. New York: Oxford University Press. Roth, W.-M., McGinn, M. K., & Bowen, G. M. (1998). How prepared are preservice teachers to teach scientific inquiry? Levels of performance in scientific representation practices. Journal of Science Teacher Education, 9, 25-48. Schwab, J. J. (1962). The teaching of science as inquiry. In J. J. Schwab & P. F. Brandweine (Eds.), The teaching of science. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press. Shuell, T. J. (1990). Teaching and learning as problem solving. Theory into Practice, 29, 102-108. Smith, P. J. III. (1996). Efficacy and teaching mathematics by telling: A challenge for refrm. Journal for Research in Mathematics Education. 27(4). 387-402. Spradley, J. P. (1980). Participant Observation. NewYork: Holt, Reinhart and Winston. Stewart, J. and Hafner, R. (1991). Extending the conception of “problem” in problemsolving research. Science Education, 75(1), 105-120. Supovitz, J. A. & Turner, H. M. (2000). The effects of professional development on science teaching practices and classroom culture. Journal of Research in Science Teaching, 37(9), 963-980. Taconis, R., Ferguson-Hessler, M. G. M., and Broekkamp, H. (2001). Teaching science problem solving: An overview of experimental work. Journal of Research in science Teaching, 38(4), 442-468. Tobin, K. & McRobbie, C. J. (1996). Cultural myths as constraints to the enacted science curriculum. Science Education, 80, 223-241. Trumbell, D. & Kerr, P. (1993). University researchers' inchoate critiques of science teaching: Implications for the content of preservice science teacher education. Science Education, 77, 301-317. van Driel, J. H., Beijaard, D., and Verloop, N. (2001). Professional development and reform in science education: The role of teachers' practical knowledge. Journal of Research in Science Teaching, 38(2), 137-158. Wallace, C., & Kang, N.(2004). An investigation of experienced secondary science teachers' beliefd about Inquiry: An examination of competing belief sets. Wertsch, J. V. (1991). Voices of the mind: a sociocultural approach to mediated action. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press. 33 Windschitl, M. (2004). Folk theories of "inquiry": How preservice teachers reproduce the discourse and practices of an Atheoretical scientific method. Journal of Research in Science Teaching, 41(5), 481-512. 34