Table 1: Number of vacancies by LLSC area and region

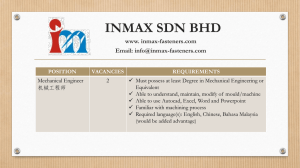

advertisement