The "Borat" Problem in Bargaining

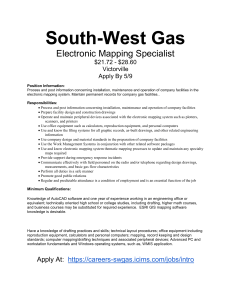

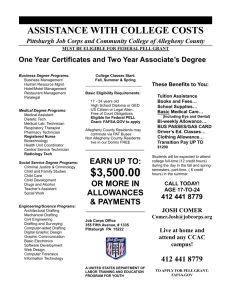

advertisement