Thermohaline circulation The water of the great world ocean is, like

From the web: http://www.killerinourmidst.com/THC.html

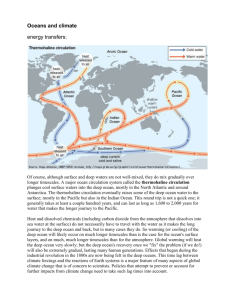

Thermohaline circulation The water of the great world ocean is, like its crust and interior, constantly in motion. Currents carrying colossal amounts of water transport it around the globe, by what has been named

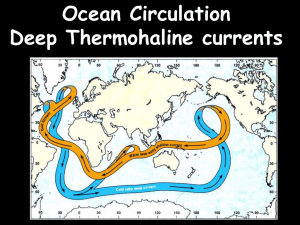

"The Great Ocean Conveyor" (Broecker, 1991). Oceanic thermohaline -- so named because it involves both heat, hence "thermo," and salt, hence haline, for common table salt (halite) -- circulation is what drives the

Conveyor. The two attributes, temperature and salinity, determine the density of seawater, and the differences in density between the water masses in the world's oceans causes the water to flow.

Thermohaline circulation -- the Great Ocean Conveyor -- thereby produces the greatest oceanic current on the planet. It works in a fashion similar to a conveyor belt -- hence the name -- transporting enormous volumes of cold, salty water from the North Atlantic to the Northern Pacific, and bringing warmer, fresher water in return.

QuickTime™ and a

decompressor are needed to see this picture.

http://www.killerinourmidst.com/grafix/THC%20Frakes.jpg

The Great Ocean Conveyer. Note that this map presents global thermohaline circulation as it presently exists. In preceeding ages, because the configuration of the continents was different, thermohaline circulation, if it existed, would also have been quite different. During the warmest periods of Earth's history, it is likely that there was no such thermohaline circulation. (Frakes, 1992, figure 10.21, p. 186, as taken from

Kerr, 1988)

Descriptions of the working of the Conveyor usually start with what happens in the North Atlantic, under and near the polar region sea ice. There warm, salty water that has been transported north from tropical regions is rapidly cooled, forming frigid water in vast quantities. When this seawater freezes, its salt is

excluded (sea ice contains almost no salt), increasing the salinity of the remaining, unfrozen water. This salinity makes the water quite dense, and its frigidity makes it denser still. Being denser than the less saline, warmer surface waters moving in from the south, this water drops to the floor of the ocean. This water is known to oceanographers as North Atlantic Deep Water (NADW), and it propels today's oceanic thermohaline circulation.

In the northernmost reaches of the North Atlantic, this water begins a great circuit through the world's oceans. First it moves south through the North Atlantic, then south through the South Atlantic, rounding

Brazil, and then encounters great masses of similarly frigid and saline water coming from under the sea ice area surrounding Antarctica (called Antarctic Bottom Water [AABW] or Antarctic Deep Water [AADW]), hugging the ocean bottom as it flows. This greatest of ocean currents then moves east, well north of the

Antarctic mainland but well south of Africa (where, past the Cape of Good Hope, a branch pushes northward along the east African coast) and continues east across the entire breadth of the Indian Ocean north of Antarctica, swings around south of Australia and far into the Pacific. As it continues on its submarine migration, the current mixes with warmer water, warms, and rises, until finally, in the northern

Pacific, it dissipates as a coherent entity.

In the Pacific, however, a warm, shallow-sea counter-current has been generated. This counter-current moves south and west, wends its way through the Indonesian archipelago, across the Indian Ocean, still heading west, and rounds southern Africa just off the Cape of Good Hope. It crosses though the South

Atlantic, still on the surface (though it extends a kilometer and a half -- almost a mile -- deep), where tropical warmth increases evaporation and leaves the counter-current saltier. It then moves up along the East Coast of North America, and on across to the coast of Scandinavia, which its warmth helps protect from the extreme cold of northern winters. When this warmer, saltier water reaches high northern latitudes, it chills, and eventually becomes North Atlantic Deep Water, completing the circuit.

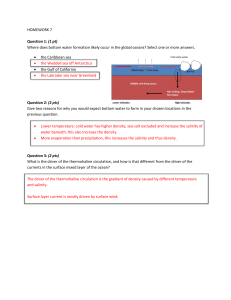

Although this global thermohaline circulation has been vigorous since the end of the ice age, the global conveyor is vulnerable to significant and rapid changes. Because the circulation is driven by the varying densities of water, it can become sluggish, or perhaps even stagnant, when those densities change. At times, frigid deep water from Antarctica has been the dominant driver of the world's circulation, which results in the cooling of surface waters in the North Atlantic and lower temperatures for coastal North America and northern Europe (Broecker, 2001). During the Ice Age, the primary driving force of global thermohaline circulation may have switched back and forth between the waters of the North Atlantic and those of

Antarctica. As the deep water driver seesawed between north and south, it produced rapid shifts of temperature for the North Atlantic region and significant climate instability (Broecker, 1997).

The density of tropical water is also quite high, though not as that of polar water. It owes this high density to the elevated rate of evaporation in tropical areas. As with the freezing of polar sea ice, evaporation leaves the salt behind in the remaining seawater. (Both freezing and evaporation therefore produce higher salinity in surface water. Being denser than the surrounding water, tropical water sinks, though because polar water is much colder and therefore denser, it sinks faster and deeper than tropical water.)

During warming episodes in Earth's history, polar regions tend to warm proportionately more than tropical regions do, and the temperature difference between the waters of the two regions decreases. Less water is frozen into ice, and salinity declines. Polar water also becomes warmer, and therefore even less dense.

Conversely, tropical water, its salinity increased by greater evaporation, becomes more dense. The density difference between polar and tropical waters decreases. This can slow, and perhaps stop, thermohaline

circulation.

(The major European and Asian rivers that empty into the Arctic Ocean have been increasing their flows

[Peterson, 2002], apparently as a result of increased high latitude precipitation due to global warming. As a consequence, deep water in Arctic seas has freshened during the past 40 years. Computer modeling indicates that the warming-induced precipitation increase can be traced only to human releases of greenhouse gases, not to natural variations in the rain cycle [Wu, 2005].)

One extremely important attribute of thermohaline circulation is that it carries oxygenated water to the deep ocean. The polar seas (the North Atlantic and the Southern Ocean) that produce the frigid water, which drives the Great Ocean Conveyer, are storm-swept, especially in winter. This turbulence oxygenates the water, and its frigidity (like a frigid can of soda) allows it to carry lots of dissolved gas. Descending to the ocean floor, this frigid water thereby oxygenates the deep sea. Without this input of highly oxygenated water, the deep ocean would become anoxic. (The activity of phytoplankton only provides oxygen to the ocean's surface.) A vigorous thermohaline circulation, therefore, translates into a well-oxygenated ocean, whereas a weak thermohaline circulation results in ocean stratification (separation into distinct deep ocean and surface ocean layers, with little mixing between them) and deep water anoxia.

During earlier periods of Earth's history, it is likely that something similar to today's thermohaline circulation occurred in the planet's oceans, especially when global climate was cool. Certainly the density variations produced by temperature and salinity differences would have existed, even if those differences were more muted. High global temperatures may have been capable of slowing, or even possibly stopping, thermohaline circulation, however. And the nature of the circulation would have been dependent on the configuration of the oceans and continents, which changed with time. Nonetheless, and perhaps surprisingly, those folks known as paleoceanographers apparently can use general principles of oceanic circulation, coupled with data on the ancient positions of oceans and continents, to make reasonably good determinations of what ocean circulation would have looked like in ages past.