Brucellosis

advertisement

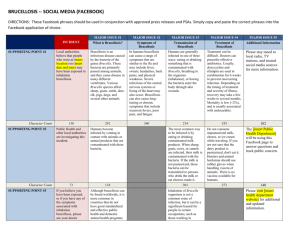

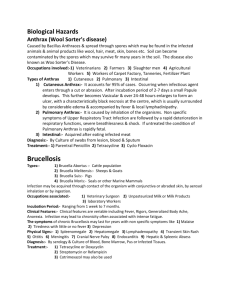

Brucellosis From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia Jump to: navigation, search Brucellosis Classification and external resources ICD-10 A23. ICD-9 023 DiseasesDB 1716 MedlinePlus 000597 eMedicine med/248 MeSH D002006 Brucellosis, also called Bang's disease, Gibraltar fever, Malta fever, Maltese fever, Mediterranean fever, rock fever, or undulant fever,[1][2] is a highly contagious zoonosis caused by ingestion of unsterilized milk or meat from infected animals, or close contact with their secretions. Transmission from human to human, for example through sexual contact or from mother to child, is exceedingly rare, but possible.[3] Brucella spp. are small, Gram-negative, non-motile, non-spore-forming rods, which function as facultative intracellular parasites that cause chronic disease, which usually persists for life. Symptoms include profuse sweating and joint and muscle pain. Brucellosis has been recognized in animals including humans since the 19th century. Contents [hide] 1 History and nomenclature 2 Brucellosis in animals o 2.1 Brucellosis in cattle o 2.2 Brucellosis in Ireland o 2.3 Brucellosis in the Greater Yellowstone area o 2.4 Brucellosis in dogs 3 Brucellosis in humans o 3.1 Symptoms o 3.2 Treatment and prevention o 3.3 Biological warfare 4 Popular culture references 5 See also 6 References 7 External links [edit] History and nomenclature The disease now called brucellosis, under the name "Mediterranean fever", first came to the attention of British medical officers in Malta during the Crimean War in the 1850s. The causal relationship between organism and disease was first established by Dr. David Bruce in 1887.[4][5] In 1897, Danish veterinarian Bernhard Bang isolated Brucella abortus as the agent, and the additional name "Bang's disease" was assigned. In modern usage, "Bang's disease" is often shortened to just "Bangs" when ranchers discuss the disease or vaccine. Maltese doctor and archaeologist Sir Temi Zammit identified unpasteurized milk as the major source of the pathogen in 1905, and it has since become known as Malta Fever, or deni rqiq locally. In cattle this disease is also known as contagious abortion and infectious abortion. The popular name "undulant fever" originates from the characteristic undulance (or "wave-like" nature) of the fever which rises and falls over weeks in untreated patients. In the 20th century, this name, along with "brucellosis" (after Brucella, named for Dr Bruce), gradually replaced the 19th century names "Mediterranean fever" and "Malta fever". In 1989, Saudi Arabian neurologists discovered neurobrucellosis, a neurological involvement in brucellosis.[6][7] The following obsolete names have previously been applied to brucellosis: Brucelliasis Bruce's septicemia continued fever Crimean fever Cyprus fever febris melitensis febris undulans goat fever melitensis septicemia melitococcosis milk sickness mountain fever Neapolitan fever slow fever [edit] Brucellosis in animals Disease incidence map of Brucella melitensis infections in animals in Europe during the first half of 2006. never reported not reported in this period confirmed clinical disease confirmed infection no information Species infecting domestic livestock are B. melitensis (goats and sheep), B. suis (pigs, see Swine brucellosis), B. abortus (cattle and bison), B. ovis (sheep), and B. canis (dogs). B. abortus also infects bison and elk in North America and B. suis is endemic in caribou. Brucella species have also been isolated from several marine mammal species (pinnipeds and cetaceans). [edit] Brucellosis in cattle The bacterium Brucella abortus is the principal cause of brucellosis in cattle. The bacteria are shed from an infected animal at or around the time of calving or abortion. Once exposed, the likelihood of an animal becoming infected is variable, depending on age, pregnancy status, and other intrinsic factors of the animal, as well as the amount of bacteria to which the animal was exposed.[8] The most common clinical signs of cattle infected with Brucella abortus are high incidences of abortions, arthritic joints and retained after-birth. There are two main causes for spontaneous abortion in animals. The first is due to erythritol, which can promote infections in the fetus and placenta. Second is due to the lack of anti-Brucella activity in the amniotic fluid. Males can also harbor the bacteria in their reproductive tracts, namely seminal vesicles, ampullae, testicles, and epididymides. Dairy herds in the USA are tested at least once a year with the Brucella Milk Ring Test (BRT).[9] Cows that are confirmed to be infected are often killed. In the United States, veterinarians are required to vaccinate all young stock, thereby further reducing the chance of zoonotic transmission. This vaccination is usually referred to as a "calfhood" vaccination. Most cattle receive a tattoo in their ear serving as proof of their vaccination status. This tattoo also includes the last digit of the year they were born.[10] Canada declared their cattle herd brucellosis-free on September 19, 1985. Brucellosis ring testing of milk and cream, as well as testing of slaughter cattle, ended April 1, 1999. Monitoring continues through auction market testing, standard disease reporting mechanisms, and testing of cattle being qualified for export to countries other than the USA.[11] The first state–federal cooperative efforts towards eradication of brucellosis caused by Brucella abortus in the U.S. began in 1934. [edit] Brucellosis in Ireland Ireland was declared free of brucellosis on 1 July 2009. The disease had troubled the country's farmers and veterinarians for several decades.[12][13] The Irish government submitted an application to the European Commission, which verified that Ireland had been liberated.[13] Brendan Smith, Ireland's Minister for Agriculture, Fisheries and Food, said the elimination of brucellosis was "a landmark in the history of disease eradication in Ireland".[12][13] Ireland's Department of Agriculture, Fisheries and Food intends to reduce its brucellosis eradication programme now that eradication has been confirmed.[12][13] [edit] Brucellosis in the Greater Yellowstone area Wild bison and elk in the Greater Yellowstone Area (GYA) are the last remaining reservoir of Brucella abortus in the U.S. The recent transmission of brucellosis from elk to cattle in Idaho and Wyoming illustrates how brucellosis in wildlife in the GYA may negatively affect cattle. Eliminating brucellosis from this area is a challenge, because these animals are on public land and there are many viewpoints involved in the management of these animals. [edit] Brucellosis in dogs The causative agent of brucellosis in dogs is Brucella canis. It is transmitted to other dogs through breeding and contact with aborted fetuses. Brucellosis can occur in humans that come in contact with infected aborted tissue or semen. The bacteria in dogs normally infect the genitals and lymphatic system, but can also spread to the eye, kidney, and intervertebral disc (causing discospondylitis). Symptoms of brucellosis in dogs include abortion in female dogs and scrotal inflammation and orchitis (inflammation of the testicles) in males. Fever is uncommon. Infection of the eye can cause uveitis, and infection of the intervertebral disc can cause pain or weakness. Blood testing of the dogs prior to breeding can prevent the spread of this disease. It is treated with antibiotics, as with humans, but it is difficult to cure.[14] [edit] Brucellosis in humans [edit] Symptoms Granuloma and necrosis in the liver of a guinea pig infected with Brucella suis Brucellosis in humans is usually associated with the consumption of unpasteurized milk and soft cheeses made from the milk of infected animals, primarily goats, infected with Brucella melitensis and with occupational exposure of laboratory workers, veterinarians and slaughterhouse workers. Some vaccines used in livestock, most notably B. abortus strain 19, also cause disease in humans if accidentally injected. Brucellosis induces inconstant fevers, sweating, weakness, anaemia, headaches, depression and muscular and bodily pain. The symptoms are like those associated with many other febrile diseases, but with emphasis on muscular pain and sweating. The duration of the disease can vary from a few weeks to many months or even years. In the first stage of the disease, septicaemia occurs and leads to the classic triad of undulant fevers, sweating (often with characteristic smell, likened to wet hay) and migratory arthralgia and myalgia. In blood tests, is characteristic the leukopenia and anaemia, some elevation of AST and ALT and positivity of classic Bengal Rose and Huddleson reactions. This complex is, at least in Portugal, known as the Malta fever. During episodes of Malta fever, melitococcemia (presence of brucellae in blood) can usually be demonstrated by means of blood culture in tryptose medium or Albini medium. If untreated, the disease can give origin to focalizations or become chronic. The focalizations of brucellosis occur usually in bones and joints and spondylodiscitis of lumbar spine accompanied by sacroiliitis is very characteristic of this disease. Orchitis is also frequent in men. Diagnosis of brucellosis relies on: 1. Demonstration of the agent: blood cultures in tryptose broth, bone marrow cultures. The growth of brucellae is extremely slow (they can take until 2 months to grow) and the culture poses a risk to laboratory personnel due to high infectivity of brucellae. 2. Demonstration of antibodies against the agent either with the classic Huddleson, Wright and/or Bengal Rose reactions, either with ELISA or the 2-mercaptoethanol assay for IgM antibodies associated with chronic disease 3. Histologic evidence of granulomatous hepatitis (hepatic biopsy) 4. Radiologic alterations in infected vertebrae: the Pedro Pons sign (preferential erosion of antero-superior corner of lumbar vertebrae) and marked osteophytosis are suspicious of brucellic spondylitis. The disease's sequelae are highly variable and may include granulomatous hepatitis, arthritis, spondylitis, anaemia, leukopenia, thrombocytopenia, meningitis, uveitis, optic neuritis and endocarditis. [edit] Treatment and prevention Antibiotics like tetracyclines, rifampicin and the aminoglycosides streptomycin and gentamicin are effective against Brucella bacteria. However, the use of more than one antibiotic is needed for several weeks, because the bacteria incubate within cells. The gold standard treatment for adults is daily intramuscular injections of streptomycin 1 g for 14 days and oral doxycycline 100 mg twice daily for 45 days (concurrently). Gentamicin 5 mg/kg by intramuscular injection once daily for 7 days is an acceptable substitute when streptomycin is not available or difficult to obtain.[15] Another widely used regimen is doxycycline plus rifampin twice daily for at least 6 weeks. This regimen has the advantage of oral administration. A triple therapy of doxycycline, together with rifampin and cotrimoxazole has been used successfully to treat neurobrucellosis.[16] Doxycycline is able to cross the blood– brain barrier, but requires the addition of two other drugs to prevent relapse. Ciprofloxacin and co-trimoxazole therapy is associated with an unacceptably high rate of relapse. In brucellic endocarditis surgery is required for an optimal outcome. Even with optimal antibrucellic therapy relapses still occur in 5–10 percent of patients with Malta fever. The main way of preventing brucellosis is by using fastidious hygiene in producing raw milk products, or by pasteurizing all milk that is to be ingested by human beings, either in its unaltered form or as a derivate, such as cheese. Experiments have shown that cotrimoxazol and rifampin are both safe drugs to use in treatment of pregnant women who have Brucellosis. [edit] Biological warfare In 1954, B. suis became the first agent weaponized by the United States at its Pine Bluff Arsenal in Arkansas. Brucella species survive well in aerosols and resist drying. Brucella and all other remaining biological weapons in the U.S. arsenal were destroyed in 1971–72 when the U.S. offensive biological weapons (BW) program was discontinued.[17] The United States BW program focused on three agents of the Brucella group: Porcine Brucellosis (Agent US) Bovine Brucellosis (Agent AB) Caprine Brucellosis (Agent AM) Agent US was in advanced development by the end of World War II. When the U.S. Air Force (USAF) wanted a biological warfare capability, the Chemical Corps offered Agent US in the M114 bomblet, based after the 4-pound bursting bomblet developed for anthrax in World War II. Though the capability was developed, operational testing indicated that the weapon was less than desirable, and the USAF termed it an interim capability until replaced by a more effective biological weapon. The main drawbacks of the M114 with Agent US was that it was incapacitating (the USAF wanted "killer" agents), the storage stability was too low to allow for storing at forward air bases, and the logistical requirements to neutralize a target were far higher than originally anticipated, requiring unreasonable logistical air support. Agents US and AB had a median infective dose of 500 org/person, and AM was 300 org/person. The rate-of-action was believed to be 2 weeks, with a duration of action of several months. The lethality estimate was based on epidemiological information at 1–2%. AM was always believed to be a more virulent disease, and a 3% fatality rate was expected. [edit] Popular culture references Lists of miscellaneous information should be avoided. Please relocate any relevant information into appropriate sections or articles. (September 2007) In A. J. Cronin's Shannon's Way, the hero devotes most of the time scale of the novel to research establishing a link between brucellosis in humans and a particular infection in milk, only to find that his results have been anticipated. In Flannery O'Connor's short story "The Enduring Chill," the protagonist Asbury is diagnosed with undulant fever. In an act of defiance against what he considers his mother's overbearing ways, he violates a strict rule on her dairy farm by drinking raw milk. The brucellosis he contracts reduces him to an invalid dependent on his mother's care. It was also mentioned in All Things Bright and Beautiful, one volume in the memoirs of James Herriot, a Scottish veterinarian who began practice in the 1930s. James Herriot is the pen name of veterinarian James Alfred Wight. In this case, the disease ruined an aspiring dairy farmer's herd and forced him to abandon the business. Wight also describes the effect of brucellosis on himself, referring to it as having "funny turns," in his fifth volume of memoirs, "Every Living Thing." The song "Play it All Night Long" from Warren Zevon's Bad Luck Streak in Dancing School references brucellosis (probably the only popular song to do so). Hillary Clinton was offered a fermented milk drink while traveling on a state trip through Mongolia when she was First Lady. When her personal physician found out she had accepted the drink, he ordered her to take a strong course of antibiotics to protect against the risk of brucellosis.[citation needed] [edit] See also Swine brucellosis Florence Nightingale (She may have suffered from brucellosis in the Crimea.) Wildlife disease Andrew Moynihan Victoria Cross recipient who died from 'Malta Fever'. [edit] References 1. ^ "Brucellosis" in the American Heritage Dictionary 2. ^ Maltese Fever by wrongdiagnosis.com, last Update: 25 February, 2009 (12:01), retrieved 2009-02-26 3. ^ "Diagnosis and Management of Acute Brucellosis in Primary Care". Brucella Subgroup of the Northern Ireland Regional Zoonoses Group. August 2004. http://www.dhsspsni.gov.uk/brucellosis-pathway.pdf. 4. ^ Wilkinson, Lise (1993). ""Brucellosis"". in Kiple, Kenneth F. (ed.). The Cambridge World History of Human Disease. Cambridge University Press). 5. ^ Brucellosis named after Sir David Bruce at Who Named It? 6. ^ Malhotra, Ravi (2004). "Saudi Arabia". Practical Neurology 4: 184–5. 7. ^ Al-Sous MW, Bohlega S, Al-Kawi MZ, Alwatban J, McLean DR (March 2004). "Neurobrucellosis: clinical and neuroimaging correlation". AJNR Am J Neuroradiol 25 (3): 395– 401. PMID 15037461. http://www.ajnr.org/cgi/pmidlookup?view=long&pmid=15037461. 8. ^ Radostits, O.M., C.C. Gay, D.C. Blood, and K.W. Hinchcliff. 2000. Veterinary Medicine, A textbook of the Diseases of Cattle, Sheep, Pigs, Goats and Horses. Harcourt Publishers Limited, London, pp. 867–882. 9. ^ Hamilton AV, Hardy AV (March 1950). "The brucella ring test; its potential value in the control of brucellosis" (PDF). Am J Public Health Nations Health 40 (3): 321–3. PMID 15405523. PMC 1528431. http://www.ajph.org/cgi/reprint/40/3/321.pdf. 10. ^ Vermont Beef Producers (PDF). How important is calfhood vaccination?. http://www.vermontbeefproducers.org/NewFiles/AsktheVet/Fall%2002.pdf. 11. ^ "Reportable Diseases". Accredited Veterinarian’s Manual. Canadian Food Inspection Agency. http://www.inspection.gc.ca/english/anima/heasan/man/avmmva/avmmva_mod8e.shtml. Retrieved 2007-03-18. 12. ^ a b c "Ireland free of brucellosis". RTÉ. 2009-07-01. http://www.rte.ie/news/2009/0701/farming.html. Retrieved 2009-07-01. 13. ^ a b c d "Ireland declared free of brucellosis". The Irish Times. 2009-07-01. http://www.irishtimes.com/newspaper/breaking/2009/0701/breaking61.htm. Retrieved 2009-0701. "Michael F Sexton, president of Veterinary Ireland, which represents vets in practice said: "Many vets and farmers in particular suffered significantly with brucellosis in past decades and it is greatly welcomed by the veterinary profession that this debilitating disease is no longer the hazard that it once was."" 14. ^ Ettinger, Stephen J.; Feldman, Edward C. (1995). Textbook of Veterinary Internal Medicine (4th ed.). W.B. Saunders Company. ISBN 0721646794. 15. ^ Hasanjani Roushan MR, Mohraz M, Hajiahmadi M, Ramzani A, Valayati AA (April 2006). "Efficacy of gentamicin plus doxycycline versus streptomycin plus doxycycline in the treatment of brucellosis in humans". Clin. Infect. Dis. 42 (8): 1075–80. doi:10.1086/501359. PMID 16575723. 16. ^ McLean DR, Russell N, Khan MY (October 1992). "Neurobrucellosis: clinical and therapeutic features". Clin. Infect. Dis. 15 (4): 582–90. PMID 1420670. 17. ^ Woods, Lt Col Jon B. (ed.) (April 2005) (PDF). USAMRIID’s Medical Management of Biological Casualties Handbook (6th ed.). Fort Detrick, Maryland: U.S. Army Medical Institute of Infectious Diseases. p. 53. http://www.usamriid.army.mil/education/bluebookpdf/USAMRIID%20BlueBook%206th%20Edi tion%20-%20Sep%202006.pdf. [edit] External links Brucella abortus biovar 1 str. 9-941 (from PATRIC, the PathoSystems Resource Integration Center, a NIAID Bioinformatics Resource Center) Brucella melitensis biovar Abortus 2308 (from PATRIC, the PathoSystems Resource Integration Center, a NIAID Bioinformatics Resource Center) Prevention about Brucellosis from Center for Disease Control Capasso L (August 2002). "Bacteria in two-millennia-old cheese, and related epizoonoses in Roman populations". J. Infect. 45 (2): 122–7. PMID 12217720. http://linkinghub.elsevier.com/retrieve/pii/S0163445302909965. – re high rate of brucellosis in humans in ancient Pompeii Brucellosis factsheet from European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control, agency of European Union 53805059 at GPnotebook Brucellosis in Dogs from The Pet Health Library Brucella from PATRIC Brucella Bioinformatics Portal Brucellosis Fact Sheet Brucellosis Brucellosis in humans Brucellosis, also known as "undulant fever", "Malta fever" or "Mediterranean fever," is primarily a disease of those whose occupations bring them into direct contact with domestic animals. (Brucella suis infection has also been documented in feral swine hunters.) The severity of human disease varies, depending largely upon the infecting strain: B. melitensis infection causes the most severe disease, followed by B. suis > B. abortus > B. canis. o B. melitensis and B. suis are more resistant to bacteriolytic factors in serum. o Of regional concern, there were 6,500 cases of human brucellosis in Mexico in 1998, many of which were attributable to B. melitensis. B. ovis is not known to be zoonotic. Modes of transmission: Transmission via unpasteurized milk and contaminated cheese was, historically, a serious problem. However, where pasteurization is practiced, such transmission is rare today the exception being an on-going risk of infection from consumption of soft cheese products. Infection today occurs most commonly by contact with placental tissues or vaginal secretions from infected animals (and to a lesser degree because of contact with blood or urine). o Contact with secretions from both domestic and exotic animals can pose risks, e.g. 5 zookeepers in Japan developed brucellosis in 2001 after attending the delivery of a baby moose. There is limited evidence of person-to-person transmission of Brucella spp.-- Venereal transmission has been reported between a laboratory worker and his spouse, and B. melitensis abscesses in a woman's breast may serve as a source of infection for her infant. Brucellosis is also a disease of concern as a bioterrorist weapon. Clinical symptoms of brucellosis in humans: The incubation period is generally 1-2 months, after which the onset of illness may be acute or insidious. Thereafter, symptoms may include: an intermittent, "undulating" fever headaches, chills, depression, profound weakness arthralgia, myalgia weight loss orchitis/epididymitis in men and spontaneous abortion in pregnant woman o Brucellosis lasts for days to months, and can be quite debilitating, although the case fatality rate is very low (except in cases of B. melitensis endocarditis). o Chronic sequelae may include sacroiliitis, hepatic disease, endocarditis, colitis and meningitis. Diagnosis is based on isolation of the organism and/or serology. A combination of doxycycline (100mg BID) (or in children, substitute with trimethoprimsulfamethoxazole to prevent dental staining) and rifampcin (600-900mg/day) for 6 weeks is the treatment of choice.