Kantian Foundations of Russian Liberal Theory: Human Dignity

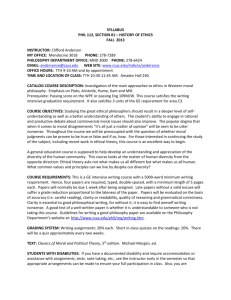

advertisement