Cascadia`s Restless Geology: Volcanoes, Earthquakes & Tsunamis

advertisement

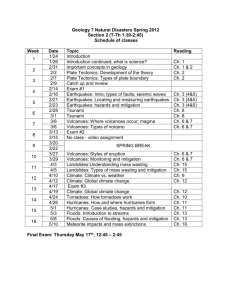

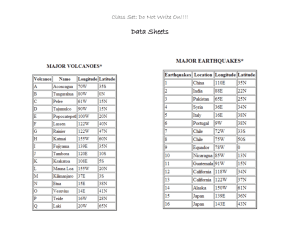

(THIS IS LONGER THAN SOME OF THE OTHER THEMES…PERHAPS SHORTEN, AND USE THE OPPORTUNTIES & CHANLLENGES FORMAT?). CASCADIA’S RESTLESS GEOLOGY: VOLCANOES, EARTHQUAKES & TSUNAMIS The tectonic forces that shape our region are responsible for both its natural beauty and its most dangerous hazards. Eastward moving Pacific oceanic plates—from north to south, the Explorer, Juan de Fuca, and Blanco Plates—are sliding under (subducting beneath) the North American continental plate. These forces have folded the Cascade Mountains, scraped off ocean floor deposits to form Washington State’s Olympics and the Coast Ranges of British Columbia, Oregon and Northern California, and created the majestic Cascadia volcanoes. But they also produce volcanic eruptions and mud flows, and earthquakes, tsunami and coastal landslides. Regional Threats Volcanoes As Mount St. Helens’ May 1980 eruptions reminded us, Cascade volcanoes are very much a present danger to those living near their slopes. Volcanic eruptions have had disastrous consequences for ports and inland navigation. Ash and pyroclastic flows from Mount St. Helens blocked the deep-draft navigation channel to the upstream Columbia River ports Earthquakes and Tsunami As strain builds and is periodically released along the junction of these moving oceanic and continental plates—the Cascadia Subduction Zone (CSZ)—great earthquakes wrack our coastal region causing the ocean floor to deform and parts of the coastline to subside. These submarine land movements generate tsunami that sweep onshore to inundate lowlying coastal areas with little warning. Except for a magnitude 7.1 event in April 1992 near Cape Mendocino, at the extreme south end of the CSZ, no earthquakes have been recorded along the fault since European settlement occurred in the mid 19th century. But, over the past decade or so, evidence of very large prehistoric earthquakes and tsunami along the CSZ has been uncovered. The best estimate of the “recurrence interval” for seven documented large Cascadia earthquakes and tsunamis is about 500 yearsThere is no way to absolutely predict when the next event will be, but we are now within the recurrence interval “window.” Two other kinds of earthquakes affect parts our region: crustal earthquakes that occur as stress is released in the upper (North American) plate, and intra-plate earthquakes that occur deep in the subducting plate. (The February 28, 2001 Magnitude 6.8 Nisqually event was an intra-plate earthquake.) Crustal earthquakes, since they occur closer to the surface, can cause terrible local damage to structures through severe ground-shaking, but are not felt at such great distances as deep intra-plate events of similar magnitude. Problems Arising from Regional Threats Managing Risk in the Face of Uncertainty Unlike other natural coastal hazards such as floods or hurricanes, earthquakes are not predictable events; they occur with no warning. The most destructive earthquakes— magnitude 7+ shallow crustal and magnitude 8+ Cascadia Subduction Zone events— recur at long, irregular intervals and have not been experienced, firsthand, by anyone alive in this region. The risk they pose, then, becomes an abstract statistical matter, of practical use in designing building codes for structural seismic resistance, but poorly understood by the lay person making choices about where to live and how to protect life and property. Warnings and Evacuation Earthquakes While no long-term predictions of earthquake occurrences can yet be made, there are promising short-term warnings being developed once an earthquake begins. Experimental work at Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory suggests that within a second of receiving the first seismic waves from sensitive instruments, computer models can quite accurately predict the time before peak ground-shaking occurs and the duration of damaging seismic waves. http://www.llnl.gov/hmc/signal-process/total.html Tsunami While there are no long term warnings for earthquakes, the events are themselves a warning for some co-seismic hazards they can produce: tsunami inundation and, in some cases, landslides. NOAA’s Deep ocean Assessment and Reporting of Tsunami (DART) tethered buoys are designed to measure actual tsunami waves underway in the ocean and provide a satellite link to broadcast accurate warnings of arrival time, though not inundation depths. http://www.pmel.noaa.gov/tsunami/Dart/ Landslides On land, steep slopes are immediately vulnerable to earthquake-generated landslides, but slides can continue for weeks afterwards, particularly where the ground is saturated. http://www.ecy.wa.gov/programs/sea/landslides/alert/alert.html Some landslides adjacent to water bodies pose another risk: they can produce local tsunami. More insidious are submarine landslides. During the Good Friday Alaskan earthquake of 1964, submarine landslides in Seward and Valdez did the greatest damage to the port and harbor areas. http://www.geocities.com/CapeCanaveral/Lab/1029/Earthquake1964Alaska.html http://www.pmel.noaa.gov/tsunami/Ws20010123/ Opportunities to Mitigate Regional Threats Evacuation Signage Locating Critical Facilities Out of Harm’s Way Making Coastal Dependent Development More Resilient