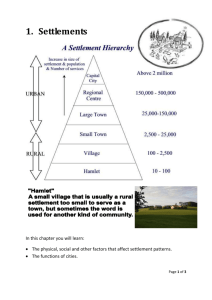

Ekurhuleni Metro Has A Population Of 2

advertisement