From: Geoff Dean, 2003

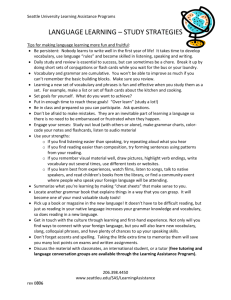

advertisement