There is a popular song in China called “Xinjiang – an adorable land”,

Unity is deep in China's blood

There is a popular song in China called “Xinjiang – an adorable land”, which gives an idyllic description of the grasslands stretching endlessly along the Tianshan Mountains, cows and sheep grazing in peace, and the enticing fragrance of grapes and melons.

Xinjiang fascinates people from all over China and the world. Last year it was visited by 22 million tourists, including 360,000 from abroad. They are attracted by its history, its scenic beauty, and, most of all, its diverse culture and warm, hospitable people, who sing, dance, and treat visitors like old friends.

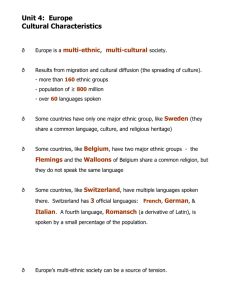

Xinjiang was an important passage for the ancient Silk Road, where people of many ethnic groups travelled, lived and traded for centuries. It has come to be defined by its multi-ethnic culture, in particular its Islamic culture. Its 21 million population now comprises 47 ethnic groups, the largest being the Uighurs, who account for 45.7%, followed by the Hans, and many others such as Kazaks, Huis, Kyrgyz, Mongolians, Tajiks,

Sibes, Manchus, Uzbeks, Russians, Daurs, and Tartars. Millions of

Muslims live there and there are 23,000 mosques. There are also

Buddhist temples and churches.

Different ethnic groups in Xinjiang have lived side by side for centuries like one big family. The relationship has been generally amicable, though,

as in all families and multi-ethnic communities, frictions occasionally happen. We call them “problems among people”, meaning they can be solved through coordination and are not a life-or-death struggle. That is why the violence in Urumqi on 5 July, causing more than 180 deaths and a thousand wounded, came as a shock.

Some blame it on a criminal case in Guangdong province earlier, which was largely fanned by a rumour. But that case was handled and the suspects detained. This can in no way justify the horrific acts of rioters in

Urumqi who, armed with sticks, knives and big stones, went on a killing rampage against innocent people. There is strong concern that outside incitement and organisation played a big part. Framing it as “ethnic conflict” is a wrong way of looking at the issue, and may also drive a wedge between ethnic groups. The incident was reminiscent of terrorist violence in Urumqi and other cities in Xinjiang in the past decade or more. Some of these terrorists were sent to train and fight in Afghanistan.

A few ended up in Guantánamo Bay. Investigation into the July 5 incident is ongoing and those who committed crimes will face the law.

China is a developing country with growing influence in the world. We are aware of the attention the world has shown to the incident.

International journalists were invited to Xinjiang and, on the whole, the world is getting an open flow of information. We hope such transparency will reduce the biased reporting and use of false information and false

photos as has happened in the past. Chinese bloggers are quite quick in responding to some unfair comments.

Now calm is being restored. People of all ethnic groups including the

Uighurs are firmly against violence and long for resuming normal life.

Xinjiang has been growing as fast as the rest of China. Many people from other parts of the country work there, especially during the cotton harvest. People from Xinjiang also work, trade and study all over the country. There is hardly a big city where there is no Uighur community.

Xinjiang restaurants in Beijing are very popular. Freedom of movement and migration is a basic human right and a sign of China’s development and progress.

Throughout the centuries, China has been a multi-ethnic society connected by a commitment to unity, prosperity and harmony. Unity is deep in the blood. That is where our strength lies, and forms the basis for

China’s interaction with the international community.

Fu Ying is the Ambassador of China to the United Kingdom