Bilingual Brain, Bilingual Plasticity

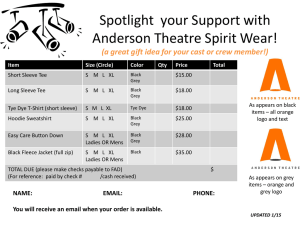

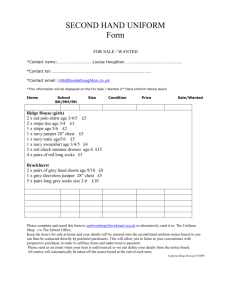

advertisement

Bilingual Brain, Bilingual Plasticity?! In 2004 a research team at the Institute of Neurology, Welcome Trust, University College London, made a neurological, controlled study into the plasticity of the bilingual brain. The aim of their research was to see if it was possible to identify differences in volume or concentration of grey or white matter in the brains of monolingual, early bilingual and late bilingual subjects. One of the team, Andrea Mechelli, shared the findings of this study with the attendees at blen’s Primary Modern Languages conference (4th February 2005). Why is grey matter density important? Does it correlate with people’s behaviour? The answer is yes. Studies have shown that decreased grey matter tends to correlate with brain abnormalities, psychological difficulties and so on. So for example it has been proven that people suffering from dyslexia have decreased grey matter density in certain parts of the brain associated with language learning – in areas of speech and co-ordination. Increased grey matter on the other hand tends to be associated with people who are high achievers. Thus children with a high IQ will normally have greater grey matter density on both the left and right hemisphere of the brain. Children who can play a musical instrument will have larger amounts of grey matter in parts of the brain associated with music learning and with coordination and hand movement. In these instances the location of the greater grey matter is very specifically related to the exact location of the brain, which the skill in question is associated. So does the bilingual brain differ from the monolingual brain? The aim of the first study undertaken by the I of N was to compare people who could only speak one language with those who could speak two. The team took a cross section of subjects 25 of who were monolingual, 25 early bilinguals and 25 late bilinguals. All the subjects were medically normal, righthanded and native English speakers. The bilinguals could additionally speak one of the following: French, German, Italian, Spanish or Dutch. Of the early bilinguals there was a combination of those whose both parents were English but they had grown up abroad and those who had one parent who was not originally from England. The team found that there were significant differences between the brains of the mono- and bilingual subjects. There was clearly an increase in grey matter density in the brains of the bilinguals in the region associated with the language system and specifically with verbal fluency. They then discovered that there was a difference again between the early and the late bilinguals with the former displaying even greater grey matter in these areas of the brain. Therefore the increase in grey matter seemed to depend on when you learn the second language as well as if you learn one at all. The research team decided from these findings to conduct a further study, looking specifically into how the age of language acquisition affects the proficiency. This experiment took 22 native Italian speakers who learnt English between 2 and 34 years of age. Each test lasted two hours and the subject was given a proficiency score at the end. Language was assessed as follows: Reading comprehension: English Vocabulary Test (written word and non-word recognition) Reading and Semantic from PALPA Written production: An Object and Action Naming Battery Frequency matched lists: low and high frequency nouns and verbs Speech comprehensions: TROG: test of reception of English grammar (auditory comprehension syntax test) Speech production: NART: national adult reading test (reading aloud regular and irregular English words) Graded Naming Test (spoken picture naming, English version) The results of these tests showed a negative correlation between the age and proficiency (p,0.01; r = -0.855). Essentially the earlier you learn the second language the more proficient you’ll be in it. These results also matched the amount of grey matter density in the subjects’ brains. Density is thus greater in subjects who are more proficient and, therefore, those who were taught it earlier in life rather than later. Why then do we see this effect in the brain? There are two possible answers to this question: 1) Due to genetic disposition. Some people may naturally have a higher density of grey matter in the language learning regions of the brain and as a result they may have a greater desire to learn a second language at an early age and a natural propensity for it. 2) Due to experience. That there are no differences in grey matter density to begin with and that it is only with the acquisition of the second language that the grey matter increases. Clues lead Mechelli to believe that the second answer is more plausible. Often the reason as to why the subjects had learnt a second language at an early age had been determined by their social circumstances and not a natural urge. For example it was because their parents had moved to another country and so on. Often, they discovered, the subjects had learnt the language by chance. This led Mechelli to conclude that this increase in grey matter in early bilinguals had occurred due to the social conditioning and experiences of the subjects and not as a result of a genetic disposition. The team are now intending on conducting further research into how grey matter may increase for bilinguals in other parts of the brain by testing Chinese subjects learning English. Mechelli asserts that these findings in the area of the bilingual brain are not exclusive to language learning. They match other studies into grey matter density relating to other skills people have. He gave three examples of such studies: 1) A study of musicians showed that there was an increase in grey matter in areas of the brain that were relative specifically to the area of the brain that the particular instrument had to use. So, for example, piano players learn bilaterally and thus there was increase in the area of the brain associated with the execution of fine movement. They also found that there was an increase of density in both left and right hemispheres of the brain, which would make sense, as pianists have to use both hands equally. Violinists on the other hand only had a significant increase in the right hemisphere. This would correlate with the fact that violinists use their left hand in a far less skilled way than their right therefore the increase in grey matter reflects this. This, Mechelli suggests, helps to prove that increases in grey matter is the result of learning and not genetics. 2) A study to investigate how taxi drivers brains function showed that they had increased grey matter in mental regions associated with space navigation and areas relative to using controls. The increase in matter was in proportion with the number of years that the taxi driver had been doing the job. 3) 80 subjects, matched for age, were divided randomly into two groups and given MRI scans. The scans of the two groups were compared and there was, unsurprisingly, no obvious differences