CELS News Article

advertisement

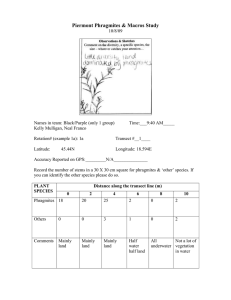

CELS News Story Summer, 2007 Can native and introduced Phragmites hybridize in the wild? By: Rudi Hempe, CELS News Editor and Reporter ---------------------------------------------------------The term “invasive species” raises a red flag for most ecologists and plants such at oriental bittersweet, purple loosestrife and exotic phragmites certainly qualify to be on the baddie list. Of the three, the latter is undergoing intense scrutiny by one CELS researcher, Dr. Laura Meyerson who is exploring the scary possibility that our native phragmites and the imported one (termed exotic) can hybridize in the wild—with potential offspring that Meyerson has dubbed “Frankenphrag” because it is unknown whether the outcome will be a species of greater or lesser vigor. One thing the environment does not need is a phragmites hybrid that has more vigor—the exotic phragmites is already causing a lot of headaches and attempts to curb its spread have involved millions of dollars. The exotic phragmites has invaded wetlands and roadsides throughout the Northeast and is a main culprit in crowding out more desirable native plant life. The phragmites reed is wind-pollinated and the native and introduced strains are subspecies and co-exist in multiple sites so hybridization is theoretically possible. “The question that I am interested in answering,” says Meyerson, “is whether the native and introduced strains have interbred.” In some cases of biological invasion, says Meyerson, “hybridization can lead to a greater invasion potential— this is what I am investigating.” Many people, explains Meyerson, have said that the native and introduced strains cannot hybridize because their flowering times do not overlap. “We have found that this is not true, at least in some cases.” Meyerson, who recently gave a lecture on her research project at MIT, showed data that stated that there was flowering overlaps (between native and exotic phragmites) as low as one day to a high of nine days, depending on the strain. Those measurements were recorded both in the field and in greenhouse experiments. So far her research has shown that the germination rates of seeds from all populations combined (either hybrid, open pollinated in the greenhouse or field collected) to be “fairly good but the highest is for the putative hybrids which could indicate an increase in vigor,” says Meyerson. Data is still being worked up but “it appears that the most vigorous plants are the results of crosses where the maternal donor comes from a single population of native phragmites,” Meyerson adds. Recently she showed a visitor some plantings of phragmites at her study site at agronomy. In several small pots hybrid seeds resulted in six stems—in just a month. In Rhode Island, the largest concentration of native phragmites (verified genetically) is on Block Island, says Meyerson. This particular strain of native phragmites is not currently known to occur anywhere else in North America. Native phragmites can grow in fresh to slightly brackish water. The exotic phragmites can grow just about everywhere, she adds. Native phragmites does not grow as tall and is not as aggressive as the exotic strains. Meyerson says she feels there are three ways we can lose native phragmites— competition with other plants such as introduced phragmites, hybridization with exotic Phragmites, and failure by managers to recognize native populations and therefore to eradicate them as they would the exotic. Her project is far from over. This summer she and her assistants will be doing more crosses in a greenhouse and in the field. They will also do “backcrosses” of hybrids to parents and perform research to confirm hybrid status and vigor. Noting that phragmites is already highly invasive, she says “We should be aware of potential increased vigor. Native phragmites is declining in many locations and knowing the potential for hybridization would help us to prioritize management and conservation actions.”