The Title - University of Cambridge

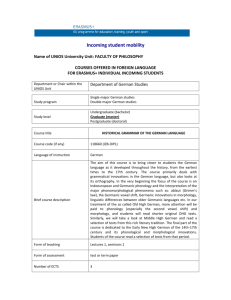

advertisement