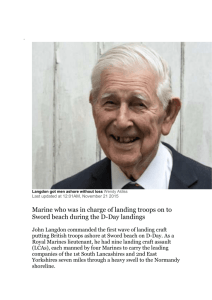

Langdon`s Critique of the So-Called “Aquatic Ape

advertisement