Base Compensation and Salary Increases

advertisement

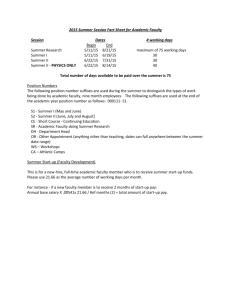

1 DRAFT Working Paper on Faculty Compensation Issues California Lutheran University May, 2006 Prepared by the Deans Council: Terry Cannings, Dean, School of Education Tim Hengst, Interim Dean, College of Arts & Sciences Chuck Maxey, Dean, School of Business Leanne Neilson, Associate Provost In the current strategic planning process, CLU has made a commitment to academic quality. We need now to manage strategically to ensure that we commit and expend resources in ways that will be most effective in achieving our goals. In part, this means recruiting and retaining the highest quality faculty members we can, adequately supporting their work and professional development, sustaining an equitable distribution of responsibilities and rewards, and encouraging and rewarding excellence. Doing so will better align our practices with our goals. Failing to do so will waste institutional resources and lessen the chances that we will be successful. It is singularly important that we begin to address faculty compensation issues on a strategic basis and attend to them first in the budget development process. An institutional commitment to specific levels of salary increases should be treated as “fact-based” in the budgeting process rather than as a more residual category. However, it is equally important that our focus be on total compensation and compensation policy and not just on base salary levels. The term “total compensation” refers to all of the financial resources expended by the University to reward and support faculty members in carrying out their institutional duties. This includes base salary, fringe benefits, professional support, paid leave (sabbatical), assigned or reassigned time for academic administration or research, etc. In many of these areas, our current faculty compensation policies and practices are inadequate in supporting and reinforcing our institutional commitment to building academic quality. This paper outlines a list of issues that need to be addressed in the context of total compensation and the strategic management of our human capital related resources. Base Compensation and Salary Increases 1. Base pay Base faculty compensation is low compared to appropriate comparison groups. It is most seriously deficient at the full professor level (see Appendix A). Recommendation: Develop a multi-year set of goals and identified funding sources for increases in overall levels of base pay. The distribution of salary increases should reflect changing market conditions, institutional priorities and merit (see below). 2 One important element in such a multi-year approach should be setting goals and identifying funding sources for annual increases in faculty base salaries on an institution-wide basis. Having such a plan in place would reassure the faculty that salary considerations do indeed have a high priority within the institution and that there is a sincere commitment on the part of the senior institutional leadership and the board to address our needs in this area. 2. Increases at Promotion and Tenure. For at least 10 years, faculty have received a $1,500 increase in salary for promotion and for tenure. These are relatively small in amount (2%-3% increase) and therefore not significant motivators nor rewards for significant professional accomplishment. Faculty members perceive (correctly) that institutional expectations for their job contributions are increasing and also that, as a result, standards for tenure and promotion are becoming more rigorous. Rewards should increase commensurately both to help enhance the incomes of those who do their work with excellence and also to convey and support the message that quality counts and higher quality counts more. Recommendation: The amount of salary increases granted at promotion and the awarding of tenure should be made larger and more meaningful. Examples of 5% or 10% increases are below. Rank Assistant Professor Associate Professor Professor Average Salary $53,200 $63,100 $72,300 5% Increase $2,660 $3,155 $3,615 10% Increase $5,320 $6,310 $7,230 3. Gender Based Differences in Pay Context: Across the nation, women faculty members earn less compensation than do their male colleagues. In a recent and typical year, the average (mean) salary for all women in the professoriate nationally was 21.8 percent less than that for men.i The reasons for this continue to be intensely researched and investigated. Essentially there are two lines of argument. One suggests that differences in pay between men and women can be accounted for by differences in their human capital (for example, greater research productivity, faster advancement in rank, or more years of service). The other argument is that there is systematic or at least pervasive discrimination against women faculty members. Both arguments appear to have some merit. One recent comprehensive empirical study indicates that about two-thirds of the pay differences between male and female faculty members nationally can be explained for differences in their human capital factors and can, therefore, be regarded as objectively based and equitable. However, the other one third of the pay difference cannot be explained by these factors, which suggests that bias may be in play.ii Over a large number of studies, the unexplained portion of the salary differences appears to be in the 6 to 10 percent range. The CLU Experience: Questions have been raised among the faculty regarding gender equity in faculty salaries at CLU. Based on the 2006-07 contracts, the Assistant Professor female salaries are slightly above male salaries. The Associate Professor and Full 3 Professor female salaries are lower than male salaries. The following table summarizes the salary differences: Assistant Professor Associate Professor Professor CLU Gender Differences -1.1% 8.4% 6.7% Nationwide Gender Differences 7.3% 6.6% 12.2% Recommendation: The most effective defense against gender discrimination in faculty pay appears to be the adoption of gender-neutral salary setting policies and practices and a firm institutional commitment to equal merit based access for men and women to appointment, promotion, tenure and pay.iii It is antithetical to our culture as a community of scholar-teachers and as a church related institution to abide discriminatory practices of any kind. CLU should explicitly and affirmatively renew its commitment to these principles. 4. Discipline-Based Differences in Pay Attracting, retaining, motivating and rewarding fairly high-performing faculty requires that we pay close attention to issues of discipline based equity. Over the past decade, CLU has necessarily (if grudgingly) moved in the direction of paying more attention to national and regional discipline-based faculty pay differentials (see Appendix B). We have done so more adequately at the entry level (Instructor and Assistant Professor) than we have at more senior ranks. And, we have done so more adequately within the arts and humanities than we have in the sciences and professional programs. One result of these changes is that we have been effective in recruiting in national labor markets in the humanities, arts and social sciences while we have generally not been effective in national markets in business, education or the physical sciences. Another result is that professional discipline faculty members are disproportionately underpaid relative to their colleagues in other institutions than are faculty members in the arts and humanities. Finally, senior level faculty members across many disciplines have not advanced in salary proportionately relative to their junior colleagues. In the instances in which these faculty members are women, these discrepancies give the appearance of being gender based inequities when, in reality, they may be discipline based inequities. Recommendation: The University needs to develop policies on rank and discipline-based pay, implement them, and address and resolve current instances of inequity. Professional and science discipline faculty members should not be disproportionately undercompensated. Many institutions have developed salary policies, guidelines and salary scales to implement equitable approaches to pay across disciplines. CLU should investigate the practices of other relevant institutions and give serious consideration to adopting such policies and practices here. 4 5. Merit Increases Current faculty compensation policies and practices give no meaningful weight to considerations of performance, or, merit. This seems fundamentally inconsistent with institutional goals and strategy that give excellence and enhanced academic quality primary roles in institutional advancement. Management practices need to be made consistent with goals and objectives. If we are striving for excellence, then excellence should be rewarded. This may well mean seeking to increase the size of the pool of funds available for faculty increases each year so that considerations of both cost of living and merit can be taken into account. Whatever the size of the pools available, more attention and weight need to be given to performance. This also means that expectations for faculty performance need to be more clearly defined and that appropriate evaluation processes are put into place. Recommendation: Consistent with its commitment to building academic quality, the University should move affirmatively to establish and implement stronger merit-based pay policies and practices and should commit to generating sufficient financial resources to pay faculty members fairly with respect to both cost of living changes and meritorious performance. Housing Housing is an obvious and pressing institutional problem and it is hoped that the current attention being paid to this issue by the University administration and the Board will result in concrete action in the near future. Helping faculty meet the demands of the regional housing market is and will remain central to our strategy of seeking to attract and retain high quality faculty members. Cost of Living: Future increases in base pay (salary pools) will need to take into account increases in the cost of living. Data for the Los Angeles regional area over the past six years indicates that the cost of living as computed by the US government has increased on an average of 3.38 percent per year. (see Appendix C). Meaningful increases in real wages (adjusted for purchasing power) can only occur if salary increases pools substantially exceed changes in the Consumer Price Index. Housing Costs: Over the past decade, housing prices in Ventura County and adjacent regions have risen substantially and are increasingly a substantial economic barrier to the attraction and retention of new faculty members. The data in Appendix C documents the alarming rates of increase in prices (the median house price in the County), the annual percentage increases in that median price, and the precipitous drop in the proportion of county residents now able to afford the median priced house. (The affordability index describes the percent of families within the county whose annual income would allow them to purchase the median price house. Since 1999, that percentage in Ventura County has fallen from 41 percent to 13.3 percent in 2005.) Recommendation: We should develop near-term policies for the provision of faculty housing assistance and be as aggressive as circumstances permit in moving ahead with a longer-term program such as creating faculty housing units on the campus. 5 Building a System for Managing Total Compensation While campus discussions frequently focus on the salary component of compensation, the reality is that the University also spends substantial amounts of money on other elements of compensation such as insurance programs, pension contributions, tuition remission, and others. When basic fringe benefits are taken into account, the actual cost to the University for an annual faculty employment contract is about 138% of base salary. Many faculty members earn additional compensation through summer or overload teaching and other assignments. Questions we should be asking ourselves include: how well are we managing this overall body of expense, and are we getting the maximum perceived value from non-salary expenditures? 1. Creating Perceived Value It is well established that levels of employee morale and motivation are significantly affected by the perceived value of compensation, not the actual dollars expended. To gain the maximum value for the money employers are paying for employees, employees must be aware of and value the pay and benefits being provided. We can do more to enhance the perceived value of our total compensation expenditures by making faculty members and other employees more aware of their total compensation packages. We should be sure that we provide as much flexibility in the benefits offered so that they match the needs and preferences of employees in various life stages and situations. We should monitor our relative standing among other appropriate institutions in terms of total compensation as well as average base salary. We do make some efforts in these areas (and in many respects our total compensation packages have very favorable elements), but we could do so more thoroughly and more systematically. Getting the best value from the total compensation resources expended requires ongoing scrutiny and adaptation. Recommendation: The University should design and implement a more proactive total compensation management system and communicate the specifics to employees. 2. Load Assignments and Overload Pay CLU currently operates from a rather traditional academic employment model under which faculty members are contractually engaged for only the nine-month academic year at a given base salary and benefits. Over time, however, the work of the University that the faculty must do has grown considerably beyond the “default” employment parameters of nine-months’ base pay in exchange for teaching 24 units and engaging in advising, committee work and scholarship. Many of our academic programs now operate on a year round basis, day and evening, in multiple locations. As the number of programs grows, so does the need for academic administration assignments. Achieving high enrollment targets increases the number of required FTE (full-time equivalent) faculty teaching slots, yet the size of the full-time or “core” faculty does not increase in proportion to program size or in terms of adding faculty where new program demands are greatest. Low faculty base salaries and the desire to place some reasonable quality limits on the proportion of teaching done by 6 adjunct faculty members motivate faculty members to take on overload teaching assignments and academic administrators to allow them (or encourage them) to do so. At the same time, increasing expectations for faculty to be teaching in graduate programs, to be productively engaged in scholarship, and to be actively participating in institutional governance are creating needs to increase the amount of paid time for faculty members to engage in these activities. Financial pressures limiting our ability to add new full time or core faculty lines compound these problems. Recommendations: Certainly, this is a complex area that requires considerable further investigation and discussion. The following is a preliminary and only partial list of goals or recommendations related to these issues: o Reduce faculty members’ reliance on overload teaching as a basic supplement to base salary levels. We should reduce the amount of overload teaching at the same time that we increase base salaries to a more market appropriate position. o Determine whether there should be load differentials for graduate and undergraduate teaching. o Develop more consistent, viable and equitable policies for compensating faculty for academic program administration and other similar assignment, whether this is through reassigned time or supplemental compensation. o Add sufficient numbers of new faculty lines, full time or part time, to meet the real staffing needs of our programs. o In the academic planning and budget development processes, make realistic assessments of and provisions for the additional staffing needs and other costs that are necessarily associated with program growth. o Carefully assess our current allocation of faculty slots, assignments, and related expenditures to match desired growth in programs quality and in meeting the needs of specific programmatic areas. Developing the appropriate information, analysis and policies in these areas will require the participation and close collaboration of leaders from the academic and administrative sectors of the University and active endorsement and commitment from the Board. Adequately Supporting Professional Development Over time, as expectations for faculty productivity in scholarship are more fully implemented and as the research orientation of the faculty grows, we must continue to add resources to support the faculty in this work and also for developmental support in their on-going efforts to refine their teaching skills and classroom effectiveness. The steps taken this past year to supplement the existing pool of faculty development funds with a base line provision of up to $1,000 for core 7 faculty members to attend appropriate professional meetings were important both symbolically and in their practical effect. We need to do more in future years and become more focused in our allocation of professional development monies. We should become more systematic about tying their allocation to institutional recognition of academic quality and to individual faculty records of activity, productivity, and achievement. Again, there is an important role for considerations of merit. Given our institutional profile and objectives, it might make sense to build a program targeting professional development resources into the following general categories of need (or opportunity): 1. Support for new faculty members We need to keep young faculty members engaged into their regional and national professional associations and provide opportunities for them to build and sustain viable programs of scholarship. This will require direct financial support for travel, meeting registration fees and expenses, research related expenses, support in identifying grant opportunities and in preparing competitive proposals. It also has implications for load and assignment profiles. Many institutions provide reduced teaching loads for new, young faculty members and/or summer support for research activities. 2. Support for more senior faculty members to build or rebuild scholarship skills As expectations change, we need to support the efforts of faculty who wish to move from a purely or primarily teaching profile to engage or re-engage research activities in their disciplines. It would be reasonable for the institution to develop criteria for the allocation of such “re-development” funds that would include elements of centrality to institutional mission and planning, programmatic development, and potential. For example, if we embrace the involvement of undergraduate students in research as an institutional hallmark, faculty development fund allocation criteria could have that as a priority. 3. Grants of time and/or money could be rewards (awards) for meritorious scholarly performance We currently have rewards for teaching excellence; we could also have them for scholarly/creative productivity. In addition, there is a need to review the current policies and practices related to the award of sabbatical leave. What will be the future demand for sabbaticals? Do we have adequate funding to support them? Should sabbatical be a right earned by time-in-grade, or should greater emphasis be placed on the scholarly merit of sabbatical proposals? And, should their awarding become more competitive? Should there be more stringent reviews of and requirements for productivity? Recommendation: We need to undertake a review of institutional practices – our own and others – as the basis for developing a set of policies and practices that will better support faculty development and scholarly productivity and that will also ensure greater return on these institutional investments. 8 i Scott Jaschik. “Explaining the Gender Gap in Pay,” Inside Higher Education, April 13, 2006: http://insidehighered.coon/layout/set/print/news/2006/04/13/gender ii Paul D. Umbach, “Gender Equity in the Academic Labor Market: An Analysis of Academic Disciplines,” Annual Meeting of the American educational Research Association, San Francisco, CA April 7-11, 2006. iii See for example, Kathleen Burke, Kevin Duncan, Lisa Krall, Deborah Spencer, “Gender differences in faculty pay and salary compression,” The Social Science Journal. 42 (2005) 165181.