FORTIFICATION AND WARRIORS

advertisement

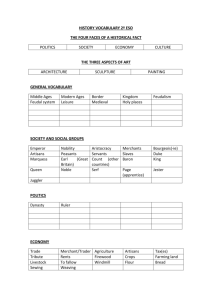

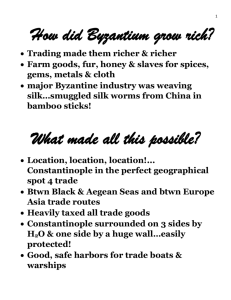

ARISTOTLE UNIVERSITY OF THESSALONIKI LAB. OF BUILDING MATERIALS PROJECT: EC FORTMED MONUMENT: CASTLE OF SERVIA SUBJECT: FORTIFICATION AND WARRIORS IN THE SOUTHERN BALKANS, A D 1000-1500 Prepared by: Plutarchos L. Theocharides Plutarchos L. Theocharides FORTIFICATION AND WARRIORS IN THE SOUTHERN BALKANS, A D 1000-1500 Byzantium, as the direct heir of the Easter Roman Empire, was also bearing the Greco-roman tradition in military organization and methods of warfare. The Byzantines, were copying, studying and working out the Hellenistic and Roman military treatises on tactics, siege warfare and war technology. At the same time, new military treatises were being complied, in contrast to what was the situation in Western Europe, during the Early and High Middle Ages. These treatises were aiming to a cool-headed and rational view of war, on the grounds of a knowledge that could be gained also academically by the future administrative and military elite of the Empire. However, Byzantium was never really advanced, in front of the ancient fortification and siege warfare tradition, being more concerned with the preservation of it, rather than with developing it. Crusedos mark, in general, a period of gradual change, after which Byzantium was declining, while Western Europe was forwarding to a technological vanguard, having made properly useful its long and close contact with the East. Control and defense of the vast Byzantine territory was made possible by a series of interdependent fortification works, ranging form the imposing walls of the large metropolitan cities, to the smaller military forts and the small fortification protecting the rural estates, to the Balkan Poninsula, the walling of the two metropolitan cities, Constantinople, capital of the empire, and Thessaloniki, was already completed in Early Christian times and was maintained effective for a thousand years, up to the Ottoman conquest. The last resistance of these two cities, in 1453 and 1430, respectively, was achieved from inside the walls and their outer defensive lines, as they were planned and formed a thousand years before, in the 5th century. This is, of course, an extreme example, indicative of the high effectiveness of those enormous enterprises of the Eastern Roman Empire, which remained outstanding, without any other similar fortification work in medieval Europe. In 1204, the sight of Constantinople was a totally incredible spectacle for the eyes of the westerners of the Fourth Crusade. The rest of the cities of Late Antiquity in the East were gradually shrunk up to the 7th century, or were abandoned and replaced by new and smaller urban centers (named “castra”), erected on steep and inaccessible sites to control and defend the productive countryside, the roads, or the passages through the mountainous country. Such a “castron” was the fortified town of Servia, controlling the mountain passage from Western Macedonia to Thessaly. The defense of fortifications against raids or long-lasting sieges, rested on the size and the successive lines of obstacles they posed to the enemy. In military theory, but also in cases like Constantinople and Thessaloniki, which were erected on plain ground, outer circuits and ditches were necessary. These elements were also keeping the siege machines of the enemy as far as possible from the main walls, particularly wheeled siege – towers, the famous “helepolois” of the Hellenistic past. At the same time, heavy artillery pieces installed on top of the tall towers of the city walls, were intending to harm enemy’s siege equipment long before it reached the outer ditch. In the case of the inaccessible “castra”-towns, however, as well as of the other forts of the mountain passages (“kleisourai”), the decisive factor was the exact and proper selection of the site for the erection of the stronghold. Byzantine military treatises vividly describe this vital need for the discovery of the proper site, a hillside, having steep slopes and even, if possible, being surrounded by a hardly dividable river, or an isolated promontory, having one and only narrow access. All these particularities were greatly reducing the significance of several hostile siege machinery. It is not therefore strange that the topic, on which the majority of the Byzantine military writers mainly insist, is the need for a careful preparation of the stronghold, in order to stand a siege. That is, gathering of foodstuffs, equipment and raw materials to serve for repairing or replacement of weapons and, also, for special constructions. Specialized craftsmen should be also available, such as carpenters, weapon-makers, tailors etc. A special attention was paid on ensuring water supply (mainly by cisterns within the castle) and on methods of avoiding threaten on aqueducts or springs. There are several cases where a water source was either incorporated in the enceinte by means of a projecting wall, or was given a safe access by means of a built, hidden corridor (fig. 1) Siege warfare employed much of archery, assault on walls and gates with battering rams and other devices, efforts to climb on the walls by wooden ladders or wooden siege-towers, and, of course, all that action aiming to the failure of such assaults. Inventiveness was of crucial importance, so engineers and skilled construction workers, mainly carpenters, were making part of the expedition armies, as well as of the defenders. The practice of tunneling for the collapse of walls and towers, was much favored from the Late Roman period (when it is also testified archeologically), up to the last siege and fall of Constantinople in 1453. This practice was equally shared by the Middle East opponents of Byzantium, Sassanians, Arabs and Turks. The besiegers were trying to undermine the walls, while the defenders were digging to break into their mines and smoke or flood out the enemy. The Byzantines favored several stone or arrow-shooting machines, like the ancient-planned catapults and ballistae and, particularly, that kind of trebouchet, which was rope – pulled and had an eastern origin. The ballista was shooting long and heavy arrows and could be mounted within the chambers of the wall –towers, while catapults were installed on the tower platforms. Large artillery of this kind had a rage up to some 400 meters. The range of a large trebuchet of the rope – pulled kind, should have been much smaller, but this machine was much more handy than the catapults. Byzantine siege artillery included also incendiary weapons which were shooting the Greek Fire. The study of Byzantine siege machinery faces, however, a serious problem in the scarcity of relevant descriptions of actual (and not only academicals) use of it, and in the lack of reliable pictorial information. Illuminated manuscripts contain some evidence, but there is often the question of whether an ancient pictorial source was simply copied, or whether an obscure, or even exaggerated ancient invention was tried to be understood (fig. 2,3) Similar is the problem, regarding the study of Byzantine armour. Armoured warriors in the Balkans were, generally speaking, more heavily protected than their eastern opponents, and less than their western ones. Yet, the serious lack of attested material evidence, in contrast with the plenty of our knowledge on oriental and western armour, poses a problem in the understanding and in reconstructing the appearance and equipment of Byzantine armies. On the other hand, the numerous pictorial sources (frescoes, illuminated manuscripts etc) share, most often, the conservatism and stylization of Byzantine art, so that their use has to be done with care )figs 3, 4) The armies of the Easter Roman Empire had already developed the Roman and Hellenistic heritage of armour, forced by the new and crucial circumstances of Late Antiquity and being, seemingly, particularly influenced by their Iranian foes Later on, Byzantine armour continued in shaping its own medieval aspect, sharing much of the Early Medieval context valid also in Western Europe and being influenced by the steppe peoples. Armor in the states of Bulgaria and Servia, which were formed later in Byzantine territory, must have been developed within the same context, as scarce archeological material demonstrates. Serbia had been influenced, in a certain degree, more directly by western European practices. Body armor consisted of iron helmet, mail corselet (or lamellar, or made of scales), pieces for the protection of arms and legs, and shields of various types and sizes (round, oval and kite shaped). Famous are the cataphract cavalry (all – armored horsemen), armed with both face an bow. Horse – archery and the bow were specially favored among the rest of medieval weaponry, listing lances, javelins, slings, swords, maces and axes. From the 12th century onwards, the number and role of mercenary troops was increased in the Byzantine armies, and also some western influence is recorded, including the use of the portable crossbow. After 1204, when Constantinople fell to the hands of the Crusaders and became the capital of a temporary Latin state for 57 years, the Byzantine territory was partitioned in several minor states. Their troops, consisting of a rich variety of warrior – types, were overrunning the land during the turbulent 13th and 14th centuries, Byzantines from the minor Greek states and afterwards from the Paleologan Empire of Constantinople, Franks from the Latin states, Serbians and Bulgarians, and, together with all the above, their mercenaries, being mainly western Europeans, Cumans (steppe – people settled around Danube) and Turks (fig. 5, 6). Ottoman Turks grew rapidly during the 14the century and entered the scene dynamically, managing to dominate all over the Balkans by the middle of the 15th century (fig. 7) Cannon seem to have been introduced in the Balkans via the Adriatic coast, and by the end of the 14th century are recorded to have been used in field action by both Serbs and Ottoman Turks. Some years later, Ottomans started developing its use in siege warfare, the example of the final siege of Constantinople in 1453 being the most celebrated. The use of cannon caused a rapid evolution and radical change in the planning of castles, yet, there wasn’t any more time for Byzantium to make use of anything of all this development in fortification. Figures 1. Plan of the Castron of Redina (after N.K. Moutsopoulos), with a built, covered tunnei, going down from the great tower – keep (nr 1) to the water reservoirs (nr 2) by the torreni 2. Battering ram on a tower – like siege machine, and a siege scaffolding with a platform on top, in an 11th century manuscript (Vatican Library) 3. A rope – pulled trebuchet, in a 13th century manuscript (Madrid, National Library) 4. Saints Mercunos and Artemios, in frescoes of the end of the 13th century (church of the Protaton, Mount Athos) 5, 6. Reconstructions of armored warriors in the LKate Byzantine Balkans, 13th and 14th centuries (after David Nicolle and Angus McBride) 7. Ottoman armor of the 15th century (metropolitan Museum, New York) Bibliography C. Foss, D. Winfield, Byzantine Fortifications, an Introduction, Pretoria 1986 F.W. Marsden, Greek and Roman Artilery, Oxford 1969 T. Kollias, Byzantinesche Wallan, Vienna 1988 D. Nicolle Hungary and the fall of Eastern Europe, 1000-1500, London 1988 P. L. Theocarides, “Hysteroromaika kai protobyzantina krane”, in Praktika tou A’ Diethnous Symposiou ke Kathemerine Zoe sto Byzantio, Athens 1989, pp. 477-506