Asking “good” questions

advertisement

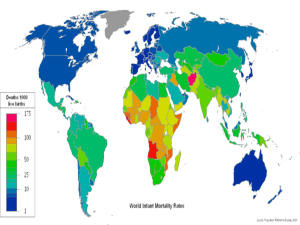

Module B1 Session 12 Asking “good” questions At the end of this session students will be able to Discuss the process of writing a question for a questionnaire Distinguish a badly written question from a well written question List 10 key points to bear in mind when writing questions for a questionnaire Appreciate the benefit of constructive criticism from colleagues and peers on the first draft of a questionnaire. Introduction Writing good questions is an art. However in the process of learning and perfecting this art, there are skills and principles that will help in designing good questions. In this session students will be asked to carry out three activities Activity 1. Key points for Question Design Each students should read the notes provided. Then working in groups of 3 or 4, they should summarise in a poster 10 key points made in the notes about Question Design. Activity 2. Writing questions In the second activity each group will be asked to draft a short questionnaire, with no more than 10 questions, that will provide enough data to explore “What is the opinion among the students of this course about the causes of global warming”. The questionnaire should allow distinguishing between the opinion of male and female students as well as allowing checking whether opinions vary according to the age of the respondents. Activity 3. Providing feedback on questions In the third activity each group will assess the draft questionnaire proposed by a different group. In this activity the key task is to provide constructive feedback on the design of the questions proposed based on the advice provided in the session notes and the posters prepared by the students. SADC Course in Statistics Module B1 Session 12 – Page 1 Module B1 Session 12 Session notes The questionnaire is the main instrument of the survey and must be prepared keeping in mind the requirements of FIVE classes of people. A few indications of these needs are given below:The client (a) (b) Does the questionnaire ask about all the topics agreed by surveyor and client? Does it search out sufficient detail in each topic? The Interviewer (a) Is it clear in what form answers are to be recorded? (b) (c) (d) Is the layout as simple as possible? Are “skip” instructions clear and kept to a minimum? Is the questionnaire of reasonable length? The Respondent (a) (b) (c) Will all the concepts implied by the questions be clearly understood by the respondent? Are questions written in the language normally used by the respondent? Are there any embarrassing or threatening questions? The Coder (a) (b) Can all conceivable responses by unambiguously coded? Can data be computerised by direct reference to response sheet without the need for a special coding operation? The Analyst (a) (b) Can all important variables be unambiguously identified and studied? Can all important relationships be analysed? SADC Course in Statistics Module B1 Session 12 – Page 2 Module B1 Session 12 General Points on Question Design 1. 2. 3. 4. 5. 6. The interviewer-administered questionnaire has to be like a conversation between the Interviewer (I) and the respondent (R). If the questions or answers make the conversation too “unnatural” e.g. embarrassing, boring or threatening, the results will not be of good quality! Writing good questions is an ART. There are a few basic principles, but the art has to be learned by EXPERIENCE, and based on broad KNOWLEDGE of the respondent population, and of how they and the interviewers will react. One individual (the surveyor) must take final responsibility for the questionnaire. While brainstorming by a team may be useful for sorting out broad topics, GOOD QUESTIONS ARE ALMOST IMPOSSIBLE TO WRITE IN COMMITTEE. After the logic of the survey has been sorted out, the CLIENT must agree that the questionnaire seems to be suitable. He must be dissuaded from “tinkering” which will “spoil the conversation”, or make the planned analyses less effective. The surveyor should make a first assessment of the impact of the questionnaire by playing the role of interviewer (preferably with some awkward specimen respondents) and the role of respondent (preferably with a specimen interviewer he does not know well). The complete document should be tested in a PILOT SURVEY, which should include interviews and coding of completed questionnaires, as well as monitoring procedures to check the effectiveness of questionnaire administration, and the quality of the data captured. SADC Course in Statistics Module B1 Session 12 – Page 3 Module B1 Session 12 Appraising each Question OBJECTIVES WHO SAID? Is including this question a direct consequence of the statement of survey targets? CONTENT WHY? WORDING HOW? What will I discover from the answer? Will the answer be meaningful and relevant? Could I leave it out? Is the question ambiguous? Are the words simple? (Specifically will they be simple for the least educated respondent)? FORM WHAT TYPE? ORDER WHERE? RELATIONSHIPS OTHER QUESTIONS? SADC Course in Statistics Open form, with prompts? Pre-coded, scaled, semantic anchors? What is the logical position for this question in the Questionnaire? What does this question add to the others? Is it here in its own right? Or is it here to clarify the answer to another question? Module B1 Session 12 – Page 4 Module B1 Session 12 Appraising Question Content 1. Ask “WHY INCLUDE IT?” An unnecessary question is costly:- (a) It uses time, which is always at a premium. (b) It has an opportunity cost – you could perhaps have asked something more relevant. (c) It will reduce efficiency; this can have a “carry-over” effect to more important questions. Respondents tire with each extra question. Interviewers sense irrelevant questions and start to ask them carelessly. 2. Ask “HOW WILL ITS RESULTS BE USED IN THE ANALYSIS?” To which conclusions will the answers contribute? If none, omit! Question may be of primary importance to survey targets. Alternatively it may serve to clarify e.g. age-group may serve to subdivide responses, and this show up a trend in an attitude with respondent age. 3. Then ask: “IS IT POSSIBLE?” (a) Will the respondent understand? (LANGUAGE, EDUCATION) (b) Will the respondent know the answer? e.g. memory fails him, e.g. he never had access to this information. (c) Is respondent motivated to give truthful answers? e.g. public interest, e.g. legal requirement. (d) Will the respondent reveal the correct answer in the interview circumstances? (FEAR, PRESTIGE) (f) Have we a way of checking the answer given? e.g. rephrase answer and say it back to respondent, e.g. ask same or related Question elsewhere in Questionnaire, e.g. external checks. SADC Course in Statistics Module B1 Session 12 – Page 5 Module B1 Session 12 Question Wording (a) IS THE WORDING SUFFICIENTLY SPECIFIC? For example, try to imagine as many meanings as possible for the question, “How many cousins do you have?” There are special pitfalls for questions about income/occupation and for attitude questions. (b) IS THE LANGUAGE SUFFICIENTLY SIMPLE/NATURAL? Questions should use the SIMPLEST possible words which will convey the EXACT MEANING. PHRASING should be as SIMPLE and INFORMAL as possible. A series of simple questions is better than one complex question. Slightly longer CONVERSATIONAL questions may be better than very short (brusque) questions. (c) AVOID AMBIGUITY Ambiguities arise in two different ways: (i) an important word may have more than one possible meaning, (ii) the question may be ambiguously phrased or be “double-barrelled”. (d) AVOID VAGUENESS e.g. “Often…”, Generally…”, “Many…”, “What kind of…?”, “Why…?” and HYPOTHETICAL QUESTIONS like, “What would you do if…?” or “would you like…?” (e) DO NOT PRESUME anything about the respondent. The common error here is to imply that the respondent “ought” to have some knowledge about a topic or that he “should” have engaged in some activity. SADC Course in Statistics Module B1 Session 12 – Page 6 Module B1 Session 12 (f) (g) DO NOT LEAD THE RESPONDENT (i) Avoid leading words which imply approval-disapproval. (ii) Take care with partial lists to jog memory (especially if included in the first question about the topic). (iii) Watch the timing of the survey and its relationship to important political/social events. DECIDE WHETHER TO PERSONALISE the question. “Do you think people ought to behave thus?” vs. “Do you behave thus? (h) BEWARE TRANSFER OF INAPPROPRIATE QUESTIONS When the original survey was designed in different circumstances, unsuitable questions can creep in, e.g. when the survey instrument was developed in another country and oversight or lack of local knowledge leads to surveys built around questions the respondent cannot possibly answer. Examples: Crop areas – has land ever been measured? Milk yields – who milks the animals? Income – does anyone keep accounts? Food consumption – who keeps records? In such cases the required information may NEVER have been known accurately by the respondent. SADC Course in Statistics Module B1 Session 12 – Page 7 Module B1 Session 12 Recall Questions Did the respondent EVER know the answer? The relevant factors in recalled knowledge are IMPORTANCE and DISTANCE. It sometimes helps to relate the event of interest to some other event which may be more important to the respondent, e.g. a festival. How serious is memory decline likely to be? It depends how important the event was AT THE TIME IT OCCURRED. What will be a suitable (CLOSED) recall period? Bias arises. Long periods tend to produce “averaging”. Short periods may cause too much variability. “Telescoping” may mean the event is wrongly remembered as occurring during the recall period. Differential recall by different groups causes bias in comparisons. Some information needs to be collected by direct observation or in two (or more) stages, “sensitising” the respondent at the first stage to general issues in the area about which more detailed recall questions follow. It may be possible to jog the memory, but remember that any specific checklist should be exhaustive or the respondent (or interviewer) is likely to be led in choosing an answer from those offered, although the “real” answer is not on the list. Can use diary method to collect longitudinal information, but this may cause problems of refusal, quality drop-off through time, biases e.g. because people behave unusually in diary period, and variation in quality of records because individuals respond differently to this time-consuming task. SADC Course in Statistics Module B1 Session 12 – Page 8 Module B1 Session 12 Opinion/Attitude Questions There is no “CORRECT” answer to a question about opinion. It is often difficult to elicit opinions in similar form from different members of a sample. Getting people to rate on a verbally anchored scale e.g. “Any fool can design a survey:strongly disagree disagree no opinion/ indifferent agree strongly agree ” Forces everyone to address the issue as posed in the question, but means that results are restricted to the “profile” of opinions for which ratings are solicited. If not thus restricted, can you ascertain what aspect of the issue the respondent had in mind? How strongly did the respondent feel about the issue? NO attitude is fixed in time. Significant events may cause changes in opinions which are sometimes quite short-lived, e.g. the attitudes of a woman to pregnancy and child-bearing during 4 weeks before and 4 weeks after delivery. There is often much difference between the “official” attitudes of a (small) society and the private views of the individuals who belong to it. A survey may reveal only the former. Attitudes can be quickly adopted, based on only brief or shallow consideration. Try to ensure you know whether the respondent had ever thought about the issue before this interview. SADC Course in Statistics Module B1 Session 12 – Page 9 Module B1 Session 12 Question Type – Open/Closed CLOSED: pre-coded, limited choice, respondent codes his or her own answer or interviewer codes it. OPEN: free choice, detailed answers, perhaps less interviewer effect, BUT it may be difficult to define codes which cover all the responses. With open questions, detail in the answer depends on how talkative the respondent is, and on how much is recorded by the enumerator. With pre-coded questions: (a) the interviewer will code and has the opportunity to know the complete answer of the respondent. However, no chance to discover errors at a later stage since the respondent’s actual answer is never recorded; (b) (c) need to prepare exhaustive and mutually exclusive lists of options; it is difficult to accommodate qualified answers (where the respondent does not really like any of the choices he is offered); if the respondent fails to understand, he can still give an apparently sensible reply. (d) (i) (ii) (iii) (iv) (v) The Gallup organisation plan to give weight to “serious” respondents:check if the respondent is already aware of the issue being investigated; use an open question to get information about the respondent’s “general feelings” on the issue; ask a series of closed questions to get his views on specific details; try to get his reasons for those views (probably by open questions); try to assess how strongly he holds his opinions. SADC Course in Statistics Module B1 Session 12 – Page 10 Module B1 Session 12 Question Order 1. It is important that opening questions should be easy to answer and should attune the respondent to the survey topic and style. 2. The sequence BROAD → SPECIFIC (FUNNEL SEQUENCE) often seems appropriate, but may have to be compromised with some of the following:- 3. The questionnaire should be designed so that the relationship between questions is obvious to respondents. When a new topic is broached this should be pointed out specifically. 4. In a well-structured questionnaire the sequence of responses should make a consistent picture in the minds of the interviewer and respondent, so that automatic checking of consistency takes place. 5. If it is essential to have concealed consistency checks, e.g. asking the same question more than once in variant phrasings, the above points may have to be sacrificed. 6. Highly sensitive questions should be left as late as possible in case they cause refusals. 7. Questions containing information should not be asked prior to those requiring knowledge. 8. Look out for FATIGUE BIAS where respondent gives obvious answers or ill-considered answers, just to get the interview over with. SADC Course in Statistics Module B1 Session 12 – Page 11 Module B1 Session 12 Practical Aspects Form design Key principles include: leaving plenty to space free for the respondent to use; leaving an amount of space suitable for the maximum reasonable length of expected response. Interviewers should be given a plentiful supply of GOOD QUALITY pens/pencils, instructed and supervised to ensure that:(a) they all write clearly, and (b) they are very careful to delete errors according to a simple convention. Physical characteristics of the document (i) (ii) (iii) (iv) (v) (vi) good quality paper and printing no bigger than clipboard printed on one side only should have standard headings each page should have a space to repeat locational information (no just the code!) as few sheets as possible (one is best!). SADC Course in Statistics Module B1 Session 12 – Page 12 Module B1 Session 12 Layout (i) (ii) (iii) (iv) (v) (vi) (vii) (viii) (ix) (x) (xi) (xii) Column widths: should depend on size of answer not length of question. This may sometimes be aided by having only abbreviated questions on the actual schedule. The UNIT in which the answer is to be recorded should be specified in the column heading; Precoding: if the codes are numeric, provide a separate box for each digit; Size of box for recording numbers should be sufficiently large to provide consistently legible answers from all interviewers under field conditions; If there are skip instructions, a complete flow chart should be drawn to check the logic. Someone should deliberately try to devise a set of feasible circumstances in which the skip instructions could go wrong; Skip instructions should depend only on the answer to the question immediately preceding the instruction; Questions should extend no more than 2/3 way across the sheet, and should be expressed, if possible, on a single line; No more than ONE question to a line; Responses should be recorded in boxes at the extreme right hand edge, where possible, and in any event in a sequence that will make for quick and accurate data entry – not artistically spread about the page; If possible, provide areas for office coding of those questions that are not self-coded; Use a different tone of shading for boxes containing data which needs to be coded (NOT TOO DARK). Check all tones, and all pens/pencils to be used for recording, to see that they are clearly legible after photocopying. SADC Course in Statistics Module B1 Session 12 – Page 13