Ryan Wittkopf

advertisement

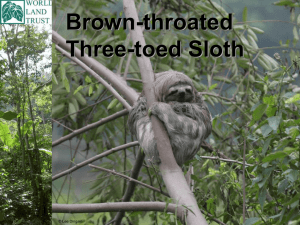

Species Account for Bradypus variegatus, Brown-Throated, Three-Toed Sloth Ryan Wittkopf Description The Brown-throated three-toed sloth, Bradypus variegatus, on average weighs between 2.25 and 6.20kg for an adult. Body length, with the head included, ranges from 413 to 700mm, and the tail is approximately 20 to 90mm. Bradypus variegatus’ overall body pledge color is a grayish brown with a darker brown forehead and suborbital markings that encircle the eye. The lengths of the forelimb appendages are longer than the hind limbs. Both limbs exhibit three digits of close proximity that extend into the characteristic three curved claws. The head of B. variegatus is small in size, compared to the rest of the body, with ears reduced beyond visible perception. The tail, also reduced in length, is stumpy. Male body coloration differs from females with the presence of an orange-yellow patch that contains a brown stripe through the middle. This patch of fur is of shorter length compared to other areas is located between the shoulders, mid dorsum. The fur of B. variegatus is coarse and thick with the strands longitudinally grooved. This groove allows for green algae to grow generating their own camouflage. The orientation of their fur is ventral to dorsal, opposite than most mammals, providing quick rain runoff. Another layer of fur is found underneath the top layer, consists of finer strands that provide more insulation. Distribution Bradypus variegatus is found only in the neotropics. They range from eastern Honduras to the northern regions of Argentina (Redford 50). The climate of this area has a constant warm temperature allowing vegetation growth through out the year. The precipitation and humidity also plays a significant role in the algae growth that serves as camouflage from predators. Ontology and Reproduction Bradypus variegatus mate once a year before the rainy season and gestation lasts between four and six months (Taube 174). The male’s role in reproduction ends after mating. Litter size is a consistent one per birth. The young will remain with the mother through lactation, approximately four months. The young become independent in another two to four months. During the time when the offspring and mother are together the young inherits the mother’s dietary preference. It is thought that this is facilitated due to the passing of microorganisms found in the stomach that is specific to the vegetation type consumed. Once the offspring becomes independent the mother will give the young part of her territory, thus lowering competition between the two (Taube 173). Behavior and Ecology Three-toed Sloths are active both diurnally and nocturnally (Redford 51). A solitary animal, Bradypus variegatus, is less aggressive than the two-toed sloth, Choloepus. That is not to say that B. variegatus will not defend itself, territory, or it’s young. If they need to defend a resource they are well equipped, their long claws can leave deep wounds (Greene 369). The only time when two B. variegatus are together with out confrontation is generally when mating. Reports of a male and a female living together are definitely not the norm. Being an arboreal specialist, B. variegatus spends the vast majority of their time in the trees. They descend from their tree top homes to defecate approximately once a week. Still clinging to the tree they will dig a hole, with their tail, defecate, cover it and ascend (Emmons 36). There is a symbiotic relationship between the sloth and a moth that forages on the algae growth. The moth not only feeds off the sloth but it also lays its eggs in the feces of the sloth. Locomotion of the sloth with in their arboreal habitat is a hand over hand motion while hanging upside down. Their long arms and legs are well suited for this; however, terrestrial movement is more of a challenge. Due to their arboreal movement being energy efficient they do not have the muscle mass needed for terrestrial locomotion. Movement on land is carried about in a crawling fashion, moving on their forearms and the soles of the hind feet. Though terrestrial movement is labored, they are skilled swimmers (Nowak 152). B. variegatus spend the greater part of their life in the mid to upper canopies hanging upside-down in tropical trees munching on young leaves, buds, and other shoot material. As many other herbivores they need to consume large quantities to obtain the necessary nutrients. This is facilitated by being able to forage with out having to use their limbs by being able to rotate their head 270°. Most mammals have seven cervical vertebrae, but, sloths possess nine. This allows for greater mobility of their head for a hands free approach to dinning. The herbivore diet as stated above is passed on from mother to offspring is folivorous, a leaf specialist (Taube 174). Due to the poor nutrient content of this diet their stomachs are compartmentalized, this extends digestion time extracting the most nutrients. Slow locomotion and a poor thermoregulation system is a direct result of this specialized diet, generally found in the Cecropia tree (Redford 51). A tree is suitable if a couple of aspects are met, a folivorous diet scheme and the canopy cover density needs to be compatible with the poor thermoregulatory system. Canopy cover density is based on the amount of sunlight that reaches the crown of the tree. Sloths use these trees as a means to regulate body temperature by simply moving in and out of the shade. Conservation Issues Bradypus variegatus is listed as an appendix two species by CITES. Meaning that they are not listed as endangered, however, they are regulated (Primack 473). Ironically since they are not threatened or endangered, there is not a whole lot of research on B. variegatus. It is known that this animal does not handle change well, thus habitat fragmentation or other alteration will have devastating effects on the survival of this animal. Works Cited Adam, Peter J. “Mammalian Species Choloepus didactylus.” American Society of Mammalogists No. 621 (1999) : 1-8. Emmons, Louise H. Neotropical Rainforest Mammals – A Field Guide. Chicago, University of Chicago Press, 1990. Feldhamer, George A, ed. et al. Mammology: Adaptation, Diversity, and Ecology second edition. New York, 2004. Greene, Harry W. “Agnostic Behavior by Three-toed Sloths, Bradypus variegatus.” Biotropica vol. 21 No. 4 (1989) : 369-372. Nowak, Ronald M. Walker’s Mammals of the World vol. 1 sixth edition. Baltimore, The Johns Hopkins University Press, 1999. Primack, Richard B. Essentials of Conservation Biology. Sunderland, Sinauer Associates Press, 1993. Redford, Kent H., John F Eisenberg. Mammals of Neotropics – the Southern Cone vol. 2. Chicago, University of Chicago Press, 1992. Taube, Erica., Joel Keravec, Jean-Chistophe Viَe, Jean-Marc Duplantier. “Reproductive biology and postnatal development in sloths, Bradypus and Choloepus: review with original data from the field (French Guiana) and captivity.” Mammal Review vol 31 No. 3 (2001) : 173-188. Reference written by Ryan Wittkopf, Biology 378 student. Edited by Christopher Yahnke. Page last updated.