The French Revolution

1789 – 1799

Underlying Causes:

The discontent of the Bourgeoisie: this interpretation stresses the

extent to which the rising middle class (merchants, bankers,

professionals and urban artisans) was kept from power. Under

the Old Regime, the King was absolute; taxes were based on

Three Estates (or classes)—Clergy; Nobles; and Everyone Else

(Third Estate was about 97% of the population)—and the first

two estates were largely free from taxation.

Ineffectiveness of the Old Regime in governing France: this

interpretation stresses the discontent of the parlements (or

regional royal courts) that had the power to “register” royal

decrees, and of the philosophes, who introduced a new language of

natural rights; AND

The Fiscal or Financial Crisis produced by borrowing to fight

wars, by the excesses at Versailles, and by the lack of a central

monetary system that could create a stable national currency.

(Almost half of the annual budget was devoted to paying interest

on the national debt.)

King Louis XVI

BEGINNINGS OF THE REVOLUTION

In 1789, the King was forced to call the Estates-General (or legislative

body)—which had last met in 1614—in order to gain approval to raise

new taxes. Banks had refused to lend anymore to the King; and bad

harvests created shortages of bread.

The Estates-General meeting in 1789

The Estates-General normally met as three separate bodies, one for

each Estate, with one vote for each Estate. Clearly, the Clergy and the

Nobles could always outvote the third estate.

When the Third Estate declared that it would meet only as a National

Assembly where all voted together by delegate, the King sent troops to

Versailles to end the “revolt”.

The Third Estate then declared itself the National Assembly and—with

the Tennis Court Oath—swore not to disband until they had created a

new constitution.

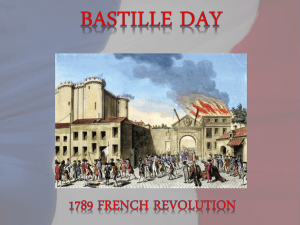

Storming of the Bastille, July 14, 1789

Tensions increased with the storming of the Bastille—in order to obtain

arms. Now the Paris common citizens, in the form of a mob, were

actively involved.

The Great Fear in the countryside: anarchy, and the destruction of

feudal records.

Declaration of the Rights of Man and the Citizen (1789)

Article 1. Men are born and remain free and equal in rights. Social

distinctions may be founded only upon the general good.

2. The aim of all political association is the preservation of the natural and

imprescriptible rights of man. These rights are liberty, property, security,

and resistance to oppression.

3. The principle of all sovereignty resides essentially in the nation. No body

nor individual may exercise any authority which does not proceed directly

from the nation.

4. Liberty consists in the freedom to do everything which injures no one

else; hence the exercise of the natural rights of each man has no limits

except those which assure to the other members of the society the

enjoyment of the same rights. These limits can only be determined by law.

5. Law can only prohibit such actions as are hurtful to society. Nothing may

be prevented which is not forbidden by law, and no one may be forced to do

anything not provided for by law.

6. Law is the expression of the general will. Every citizen has a right to

participate personally, or through his representative, in its formation. It

must be the same for all, whether it protects or punishes. All citizens, being

equal in the eyes of the law, are equally eligible to all dignities and to all

public positions and occupations, according to their abilities, and without

distinction except that of their virtues and talents.

7. No person shall be accused, arrested, or imprisoned except in the cases

and according to the forms prescribed by law. Any one soliciting,

transmitting, executing, or causing to be executed, any arbitrary order, shall

be punished. But any citizen summoned or arrested in virtue of the law shall

submit without delay, as resistance constitutes an offense.

8. The law shall provide for such punishments only as are strictly and

obviously necessary, and no one shall suffer punishment except it be legally

inflicted in virtue of a law passed and promulgated before the commission

of the offense.

9. As all persons are held innocent until they shall have been declared

guilty, if arrest shall be deemed indispensable, all harshness not essential to

the securing of the prisoner's person shall be severely repressed by law.

10. No one shall be disquieted on account of his opinions, including his

religious views, provided their manifestation does not disturb the public

order established by law.

11. The free communication of ideas and opinions is one of the most

precious of the rights of man. Every citizen may, accordingly, speak, write,

and print with freedom, but shall be responsible for such abuses of this

freedom as shall be defined by law.

12. The security of the rights of man and of the citizen requires public

military forces. These forces are, therefore, established for the good of all

and not for the personal advantage of those to whom they shall be intrusted.

13. A common contribution is essential for the maintenance of the public

forces and for the cost of administration. This should be equitably

distributed among all the citizens in proportion to their means.

14. All the citizens have a right to decide, either personally or by their

representatives, as to the necessity of the public contribution; to grant this

freely; to know to what uses it is put; and to fix the proportion, the mode of

assessment and of collection and the duration of the taxes.

15. Society has the right to require of every public agent an account of his

administration.

16. A society in which the observance of the law is not assured, nor the

separation of powers defined, has no constitution at all.

17. Since property is an inviolable and sacred right, no one shall be

deprived thereof except where public necessity, legally determined, shall

clearly demand it, and then only on condition that the owner shall have

been previously and equitably indemnified.

Source: Robinson, James, ed., Readings in European History. Boston &

New York: Ginn & Co., 1904.1 from Microsoft Encarta Encyl. DeLuxe

1"The Rights of Man Declaration."Microsoft® Encarta® Encyclopedia 2001. © 19932000 Microsoft Corporation. All rights reserved.

Marie-Antoinette, Queen of France

Paris Women’s March on Versailles (1789)

The issues were the price of bread; and hatred of Marie Antoinette and

of the rumored promiscuity of Versailles.

The result was the return of the Royal Family—and of the National

Assembly—to Paris.

Constitution of 1791 creates a constitutional monarchy, with most

power in the hands of the Legislative Assembly.

After Louis attempts to escape from France, revolutionaries fear that

French émigrés will combine with conservative Austria and Prussia to

defeat France. The result: France declares war on Austria in 1792

AND Parisian crowds become even more distrustful, especially of the

Royal family.

The second constitution creates the 1st French Republic (1792-1795).

Months are renamed

New currency is issued

Metric system introduced

Citizen and citizeness

Louis XVI beheaded in 1793

Growth in power of the Parisian mob, and of the Jacobins

Revolutionary war against the rest of Europe – 1793

Assignats: French currency issues between 1789 – 1796 and backed by

confiscated Church and royal lands.

Robespierre

The Reign of Terror

1793 - 1794

Robespierre on why the King must die—without trial.

What is the conduct prescribed by sound policy to cement the republic? It is

to engrave deeply into all hearts a contempt for royalty, and to strike terror

into the partisans of the King. To place his crime before the world as a

problem, his cause as the object of the most imposing discussion that ever

existed, to place an immeasurable space between the memory of what he

was and the title of a citizen, is the very way to make him most dangerous

to liberty. Louis XVI was king, and the republic is established. The

question is solved by this single fact. Louis is dethroned by his crimes, he

conspired against the republic; either he is condemned or the republic is not

acquitted. To propose the trial of Louis XVI is to question the Revolution.

If he may be tried, he may be acquitted; if he may be acquitted, he may be

innocent. But, if he be innocent, what becomes of the Revolution? If he be

innocent, what are we but his calumniators? The coalition is just; his

imprisonment is a crime; all the patriots are guilty; and the great cause

which for so many centuries has been debated between crime and virtue,

between liberty and tyranny, is finally decided in favour of crime and

despotism!

Citizens, beware! you are misled by false notions. The majestic movements

of a great people, the sublime impulses of virtue present themselves as the

eruption of a volcano, and as the overthrow of political society. When a

nation is forced to recur to the right of insurrection, it returns to its original

state. How can the tyrant appeal to the social compact? He has destroyed it!

What laws replace it? Those of nature: the people's safety. The right to

punish the tyrant or to dethrone him is the same thing. Insurrection is the

trial of the tyrant—his sentence is his fall from power; his punishment is

exacted by the liberty of the people. The people dart their thunderbolts, that

is, their sentence; they do not condemn kings, they suppress them—thrust

them back again into nothingness. In what republic was the right of

punishing a tyrant ever deemed a question? Was [6th-century-BC Roman

king] Tarquin tried? What would have been said in Rome if any one had

undertaken his defence? Yet we demand advocates for Louis! They hope to

gain the cause; otherwise we are only acting an absurd farce in the face of

Europe. And we dare to talk of a republic! Ah! we are so pitiful for

oppressors because we are pitiless towards the oppressed!

Two months since, and who would have imagined there could be a question

here of the inviolability of kings? Yet today a member of the National

Convention, Citizen [Jérỗme] Pétion, brings the question before you as

though it were one for serious deliberation! O crime! O shame! The tribune

of the French people has echoed the panegyric of Louis XVI. Louis

combats us from the depths of his prison, and you ask if he be guilty, and if

he may be treated as an enemy. Will you allow the Constitution to be

invoked in his favour? If so, the Constitution condemns you; it forbids you

to overturn it. Go, then, to the feet of the tyrant and implore his pardon and

clemency.

But there is another difficulty—to what punishment shall we condemn him?

The punishment of death is too cruel, says one. No, says another, life is

more cruel still, and we must condemn him to live. Advocates, is it from

pity or from cruelty you wish to annul the punishment of crimes? For

myself I abhor the penalty of death; I neither love nor hate Louis; I hate

nothing but his crimes. I demanded the abolition of capital punishment in

the Constituent Assembly, and it is not my fault if the first principles of

reason have appeared moral and judicial heresies. But you who never

thought this mercy should be exercised in favour of those whose offences

are pardonable, by what fatality are you reminded of your humanity to

plead the cause of the greatest of criminals? You ask an exception from the

punishment of death for him who alone could render it legitimate! A

dethroned king in the very heart of a republic not yet cemented! A king

whose very name draws foreign wars on the nation! Neither prison nor exile

can make his an innocent existence. It is with regret I pronounce the fatal

truth! Louis must perish rather than a hundred thousand virtuous citizens!

Louis must perish because our country must live!

Source: The Penguin Book of Historic Speeches. MacArthur, Brian, ed.

Penguin Books, 1996.2

Thermidorian Reaction: 1794 – 1795

Army is used to put down mob uprisings and to restore order.

Coup d’etat – NAPOLEON

1799

Napoleon

2"Robespierre: "Louis Must Perish"."Microsoft® Encarta® Encyclopedia 2001. © 19932000 Microsoft Corporation. All rights reserved.