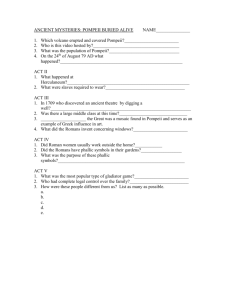

THE DISCOVERY AND EXCAVATION OF

advertisement

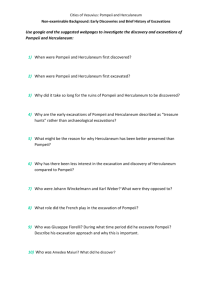

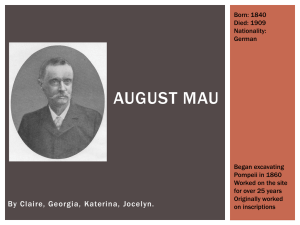

THE DISCOVERY AND EXCAVATION OF POMPEII & HERCULANEUM PERSON Workmen Workmen Rocco de Alcubierre 1738-? Spanish Francois Mazois French architect ARCHAEOLOGIST Karl Weber Francesco la Vega 16TH TO 19TH CENTURIES ACTIVITY AT SITE RESULT Digging a canal Accidental discovery of Pompeii Architect of project recorded the discovery of inscriptions Digging for limestone Led to accidental discovery of Herculaneum Dug at site where Fontana found Thought he found site of Stabiae inscriptions Was directing mining operations Found frescoes, statues, artefacts for King of Naples Filled in holes once they took everything – criticised by Cardinal Qurini Inscription found which read ‘res publica First identification of site of Pompeii; inscription translated Pompeianorum’ as ‘state of Pompeians’ Record the site, find treasure Team of 1500 men excavated and made accurate records (The Ruins of Pompeii) Treasure hunting Both sites looted Paintings cut from walls Mosaics lifted from floors Statues, columns, vases, coins removed and added to collections of kings, museums and private individuals METHODS OF EXCAVATION RESULTS & DISCOVERIES Giuseppe Fiorelli “It is hard to exaggerate his impact on the history of Pompeii…Fiorelli remains the individual who had the greatest impact upon the way in which Pompeii has been both excavated and perceived” Cooley Michele Ruggiero 1875-93 Excavation primarily focussed in northern most quarters – Central Baths, House of the Centenary, House of the Vettii uncovered Guilio De Petra 1893-1901 Investigated areas outside the city walls Ettore Pais 1901-05 Excavated the remains of the Vesuvian Gate and the water tower Antonio Sogliano Devoted himself to conservation Directors at Pompeii – all Italian 1905-10 August Mau 1873-1909 German Studied art and architecture Worked under the direction of Fiorelli, 1860’s His own work was influenced by Fiorelli’s systematic work Spent his summers excavating and his winters analysing Stayed for 25 years Mau sorted paintings into four styles. This was very important because not only did it teach about the aesthetics of Pompeii and decoration within houses, but it helped to date houses and is still being used today. 1st Style: ‘Incrustation Style’ 150-90BC Imitates coloured marble blocks by moulding plaster and painting it to resemble the same traits as marble. Influenced by blocks of marble used in temples. Very simple. Examples are seen in the House of the Faun. 2nd Style: ‘Architectural Style’ 90-25BC Roman influence. Is an elaboration of the first style minus the moulded plaster work and plus an emphasis on architectural reality. Columns, doors and ledges were all painted as realistically as possibly and were in proper perspective. Receding views were created through the use of columns which depicted scenes with a mix of reality and illusion (like windows.) Examples can be found in the Villa of Mysteries. 3rd Style: ‘Ornate Style’ 25BC-AD40 Developed from the third style in the late Augustan period. Perspective is lost and the wall paintings become flat and the architectural detail becomes unrealistic. Mythological scenes are depicted and surrounded by flat columns and ornate panels, creating the sense of a ‘shrine’. Examples are in the House of Marcus Lucretius Fronto. 4th Style: ‘Intricate Style’ AD40 onwards A combination of the second and third styles. Architectural details are somewhere in the middle, being neither as solid in the second style or as unrealistic as in the third style. Scenes are framed by panels to create ‘windows’ and ornamental motifs and figures are more popular and can be found floating freely or perched upon columns and panels. Famous examples include those in the House of the Vetti. ARCHAEOLOGIST Vittorio Spinazzola “One of the greatest problems facing Spinazzola when excavating the 20th CENTURY METHODS OF EXCAVATION RESULTS AND DISCOVERIES Abundance Way was how to consolidate the structural elements and the facades of the buildings. Since digging started from the upper layers along the street, the risk was that the facades might collapse under the weight of the mass of earth lying behind. Tremendous care went into removing the rooves of the buildings, trying to replace them on their original bearing structures, and into recomposing all the elevations, such as windows, shutters, doors and architectural cornices.” Amedeo Maiuri “towering figure…endlessly energetic, learned and imaginative” Andrew Wallace-Hadrill “his massive presence lies behind the excavation, publication and interpretation of the majority of houses” Wallace-Hadrill Wilhelmina Jashemski Fausto Zevi Italian 1977 – 1998 Superintendent of Pompeii Joined fragments of inscriptions found in different locations When he became superintendent, photographic and computer assisted documentation became a high priority. He found a number of second-style wall decorations preserved in villas Pietro Giovanni Guzzo Italian 1995Superintendent of Pompeii Only way to save Pompeii, he believes, is to stop all new excavations “Archaeology is about solving historical problems, not finding buried treasure” Also involved with the debate about the Villa of the Papyri – to dig or not to dig Makes restoration and maintenance of endangered structures a priority Financial difficulty and tourism creates conservation problems An important step in 1997 was the law passed that allowed Guzzo to retain all revenue from the gate receipts ARCHAEOLOGIST Estelle Lazer Sara Bisel American Died in 1996 John Dobbins American 1994-2006 Works at University of Virginia as professor in Roman art and archaeology Director of the Pompeii Forum Project Numerous publications that provide detail of buildings decoration and excavation in Pompeii Andrew WallaceHadrill (British) and The Herculaneum Conservation Project 2000HCP is a collaborative venture between the Soprintendenza Archaeologica di Pompee, the Packard Humanities Institute and the British School of Rome. The project was developed in 2000 by Dr. David W. Packard and Professor Andrew Wallace-Hadrill who agreed with Professor Pietro Giovanni Guzzo that there should be an exploration of a major collaborative project. In May 2001, HCP was set up as a collaborative venture with the METHODS OF EXCAVATION Studied bones in Herculanuem – sponsored by National Geographic. Looked at 139 skeletons. Was criticised for giving the skeletons names and ‘life stories’. Focus on general urban layout and the position of buildings in relation to each other Use of program AutoCAD program to precisely electronically document the layout RESULTS AND DISCOVERIES Discovered average heights, excellent health of teeth, surgical procedures done, no sign of lead poisoning. A post- earthquake (after 62AD) plan to upgrade and change street layout Shows ambition to rebuild in a grander scale and proof that the Pompeiian society was not in society was not in a economic downslide but an urban upgrade after the 62 earthquake Proposes that the earthquake in AD 62 was an opportunity to recreate the forum Surveyed and provided a reinterpretation of the building of Eumachia principal objectives of conserving and enhancing the ancient city of Herculaneum. Jaye Pont (McKenzieClarke) Australian Potter by trade Discovered people who lived in Pompeii bought their pottery locally and didn't import it. She looked at a particular type of red pottery from a city block in Pompeii that had been buried beneath rubble from the Mount Vesuvius eruption in 79 AD. This type of pottery was made by dipping a partly dried plate or bowl into a water-and-clay mix called slip. The vessel would then be fired to give it a red, shiny colour. All the "imported" pottery was local. Inhabitants of Pompeii and other areas such as northern Africa, where the pottery is also found, were thought to have traded extensively with the eastern Roman Empire. Pont said archaeologists made the mistake of thinking the pottery was imported because there was a lot of variation in the colour and quality of the local pottery compared to the pottery from northern Italy. She said archaeologists rely a lot on colour to differentiate vessels. She has only excavated one city block. Before her work, archaeologists had thought much of this pottery was imported from the eastern Roman Empire based at Constantinople, with the rest coming from northern Italy and Gallic France. Her research would "turned upside down" old notions of commerce and trade between Pompeii and the eastern Roman Empire. Not one piece of pottery found was imported.