Spring 2001 - University of Southern California

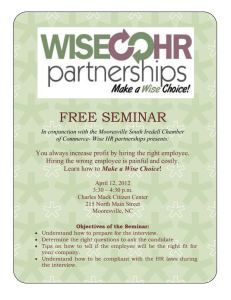

advertisement

1 Spring 2011 Sociology 524 University of Southern California seminar time: Mon. 9:30-12:20 Paul Lichterman office: 356 Kaprielian phone: 213-821-2331; 740-3533 office hours: Mons. 1:30-3:00 or by appt. Advanced Qualitative Research Methods Course Topic This is the second seminar in a two-semester sequence intended to teach professional-level qualitative research skills. We will build on and go more intensively into topics introduced last semester, and introduce other skills and criteria for evaluating qualitative research projects in social science. Course Description We will practice using the forms of analysis and standards of evaluation introduced last semester. We also will talk at some length about professional, moral, political and other issues embedded in qualitative research, especially as they emerge during the writing and publication process. You will continue working on research projects begun during the fall semester. Most if not all of you will develop comparison groups either beyond or inside your site, to strengthen your emerging arguments. You will complete a final paper with a research appendix that discusses your professional and moral/political stance toward your audiences and the people you studied. Work in the spring seminar includes: writing field notes on your site(s) regularly; carrying out interview research; writing analytic memos; discussing your own and other students' field notes and transcripts intensively, and writing comments on others' notes and transcripts. We will revisit the book-length studies from last semester, with different concerns in mind. Required Reading Common readings: These will be relatively light, as you continue delving into your research sites and developing comparison cases. All will come either from journal articles or book chapters available as photocopies, or from the required books we used the first semester. The required books were and are: Japonica Brown-Saracino, A Neighborhood that Never Changes: Gentrification, Social Preservation and the Search for Authenticity. Paul Lichterman, Elusive Togetherness: Church Groups Trying to Bridge America’s Divisions. Michael Burawoy et al., Ethnography Unbound. Anselm Strauss and Juliet Corbin, Basics of Qualitative Research (2nd edition, 1998) (available in photocopy form). Individual project readings: This semester it is especially important to find readings specific to your evolving research question. I will make suggestions if I know your subject area, but you need to take initiative and discover readings that advance your project. I may urge you to consider certain readings in relation to your project, and will expect you to do so unless you have a good reason not to. Deciding which readings or which literatures are the most relevant is, as you’ll recall, a crucial part of the process and rarely if ever obvious. It depends on what your 2 case is a “case of,” and what larger social context you think is the best for your write-up of your project. Class discussions of individual research projects This semester, you will all discuss your ongoing projects at least twice--but probably more often depending on the size of our seminar, write comments on other presenters’ field notes and memos and give your comments to the presenter. We will do this according to a schedule we work out in seminar. Regular attendance and participation is absolutely crucial for your own projects and your developing research acumen. Most seminar days we will discuss either one or two projects, depending on the subject for that day. Each of our project discussions ought to be about 45 minutes. Yes, our discussions of projects will be longer than most of last semester’s. For your first discussion you will offer field notes and a short analytic memo. For your second discussion, later in the semester, you will offer a longer analytic memo with only excerpts from field notes that you use to support the points in your memo. The balance of writing will change this semester as you develop interpretations and arguments. We will discuss this more in seminar. The best comments are ones that you think will advance a colleague's project, even if they may seem critical or hard for your colleague to hear. Your comments might: •ask questions or offer hunches about your colleague's observations •offer an alternative to her/his interpretation of some event •suggest new types of individuals or groups to observe at the field site in question •suggest an alternative argument, or literature with which to “dialogue” Summary of requirements and grading a) participant-observation in the field, for the equivalent of roughly once a week, 1 1/2 (or more) hours each time, for at least the majority of the semester. You will need time and flexibility enough to find a comparison site, or else work at developing a distinction between kinds of people or situations at the site you have been studying. If you have a (geographically separate) comparison site, you probably will spend much less time with it than with your primary site. The last several weeks you might draw back as you interview more, or consolidate an argument by writing memos. b) Interview research, to the extent your own project’s needs dictate. We will discuss this in seminar. Everyone will need to do at least two interviews, in order to practice skills specific to interviewing. c) two short memos, each meant to give you further practice with one aspect of qualitative research. Due dates are noted below; we will discuss these more in seminar. 3 d) two or more samples of field note writing from your project, once earlier and once later in the semester; written comments on selected other students’ field notes distributed to the class. e) a final paper (rougly 25 pp.) which makes a social-scientific argument based on your field notes and draws on 6 or more scholarly works (articles or books) relevant to your project. We will discuss the character of this final paper in seminar. f) The 25 pp. includes a roughly 4 page appendix in which you will reflect on the stance you chose, implicitly or explicitly, as a writer in relation to your audiences, the people you studied, the world at large. Readings and discussions in our seminar will help you a great deal with thinking about the appendix. If you care to write a longer appendix, that is fine. g) engaged participation in discussion. It really is important to talk about other people’s projects and it really is good for your own ethnographic imagination. You can’t expect to get an ‘A’ in the seminar if you do not enter the discussions of other people’s projects. For several of our sessions, we will have seminar participants introduce questions or critiques to get our discussion started. Evaluating: final paper with appendix, based on your research =60% of grade Two sets of field notes/memos distributed to class; written comments on other students’ notes or transcripts; active participation in seminar =20% two exercises =20% (#1=10, #2=10) Course schedule – SUBJECT TO REVISION, depending on how your projects are going (p) designates photocopied reading Week 1, January 10 Reconvene: review the first semester briefly, catch up on projects, course arrangements Week 2, January 24 Different kinds of interpretation (p) Erving Goffman, selections from “The Nature of Deference and Demeanor,” in 4 Interaction Ritual (Garden City, NY: Anchor Books, 1967), 56-81; 85-90. (p) Erving Goffman, “Engagements among the Unacquainted,” in Behavior in Public Places (Glencoe: The Free Press, 1963), 124-148. (p) Paul Willis, selection from Learning to Labor (New York: Columbia Univ. Press, 1977), 11-35. (p) Nina Eliasoph and Paul Lichterman, “Culture in Interaction,” American Journal of Sociology 108(4): 735-794 (2003). We begin with a quick review of our sessions on interpretation last semester and then go deeper: What different frameworks are there for interpreting? How might we interpret action when the actors don’t talk much to each other? How do we accommodate the frequent observation that the same words and phrases mean different things in different settings? We will contrast the “thin” interpretations of Goffman with the “thicker” ones of Willis and Eliasoph/Lichterman, and see how different conceptions of culture lead to different modes of interpretation. We can contrast all of these with Brown-Saracino’s Chicago-school interactionism. **This week’s reading load will seem heavy, and it is, since we have two weeks to read and think about the material. Week 3, January 31 Re-introduction to qualitative interviewing. Please review these readings from last semester: (p) "Listen before you leap: toward methodological sophistication," pp. 93112 in C. Briggs, Learning How to Ask. (p) selection on interviewing, pp. 112-126 in Hammersley, Ethnography: Principles in Practice. We will re-introduce the differences between interview and participant-observation data. We will discuss why and how we integrate interview data into our projects and consider the characteristics of the interviewer-interviewee relationship in different settings. Recommended: James Spradley, The Ethnographic Interview. Week 4, February 7 Writing an interview instrument Reading TBA. 5 We will discuss one or two studies as illustrations of interview methodology. We will distinguish between two modes of interviewing, as we did fall semester. We will discuss several of your projects with this distinction in mind, preparing you to develop interview instruments appropriate to your projects. Recommended: Arlie Hochschild, The Time Bind. Barbara Myerhoff, Number Our Days. Week 5, February 14 Interviewing workshop **Exercise 1 (on interview questions) due TODAY No new reading unless the seminar decides to choose one. Our emphasis this week is on crafting good questions in light of our previous readings and discussions. Using your exercises as examples, we will work on different kinds of interview questions and critique your drafts of questions, with an emphasis on in-depth, interpretive interviewing. no seminar February 21: Presidents’ Day Week 6, February 28 Theoretical imagination beyond the extended case method: other ways of using pre-existing theory and literatures (p) Susan Eckstein, “Community as Gift-Giving: Collectivistic Roots of Volunteerism.” American Sociological Review 66: 829-851. So far the extended case method has been our main guide to a strong theoretical imagination; what are other ways of writing up field evidence in relation to pre-existing theory? One way is to construct a “deviant case.” We will revisit the Eckstein piece from last semester and look closely at how the author uses other research literature. Let’s read also with the role of comparisons in mind and discuss the roles of short-range and longrange comparisons in your projects. Week 7, March 7 Analyzing interview materials (p) Basics of Qualitative Research, pp. 40-42, 57-71, 93-99, 101-121, 201-215. 6 (same material we used from Strauss and Corbin last semester) By now a number of you will have interview transcripts. We should review coding skills quickly and discuss their application to interview transcripts, keeping in mind the differences between interview and ethnographic evidence. I will ask one or two of you to bring a transcript along with the interview instrument you were using, and a brief explanation of what you wanted to learn from the interview. We will consider interview evidence also as grounds for defining comparison cases (inside or beyond your first field site). no seminar on March 14: spring break Week 8, March 21 Writing theory into ethnography: Opportunities and perils **Exercise 2 due TODAY (on theoretical imagination in your project) Paul Lichterman, Elusive Togetherness: Church Groups Trying to Bridge America’s Divisions. (same chapters as last semester, and Appendix I) (p) “Good Intentions Are Not Always Enough,” Chronicle (Published for USC faculty and Staff), October 24, 2005, pp. 1+. (p) Letter from a reader in Wisconsin. Does theoretical writing make ethnographic work harder to communicate to the media, or to people similar to the ones studied? Let’s consider the virtues and drawbacks of theoretically driven qualitative research as we keep discussing the choices we make as writers. Let’s also read with an eye for the use of comparison cases. Week 9, March 28 Between researcher, the researched, and wider audiences: official morality and politics of the profession (p) ASA Code of Ethics, selections from 1989 and 1997 versions This week we begin discussing different relations that researchers construct with the researched as they write up and circulate their research. These are ethical, political and moral issues of a different sort from those we most often discuss under the rubric of “research ethics” and they often are more difficult. The American Sociological Association’s Code of Ethics has begun to address these broader moral and political issues in participant observation. What do you think of ASA’s earlier and later statement of professional principles? 7 Some scholars argue that most if not all forms of social research raise these moral and political issues at least implicitly. They become explicit with ethnographic and interview research more often than other methods. As with most of our readings, the main issues exist beyond the sociology profession itself and should interest any social researcher. Week 10, April 4 Between researcher, the researched, and wider audiences: critical-reflexive sociology (p) Pierre Bourdieu and Loic Wacquant, An Invitation to Reflexive Sociology, pp. 36-59 (253-260 recommended). Recommended: Alvin Gouldner, “The Sociologist as Partisan: Sociology and the Welfare State.” American Sociologist 3: 103–16 (1968). Edward Shils, “The Calling of Sociology,” in Parsons et al., Theories of Society, pp. 1405-1448. Bourdieu’s reflexive, or critical, sociology offers another set of answers to moral and political questions we confront unavoidably. What does Bourdieu’s stance imply about the ways we pose research questions, write up and circulate our research? Week 11, April 11 Between researcher, the researched and wider audiences: “public sociology” (p) Michael Burawoy, “For Public Sociology,” American Sociological Review 70: 4-28 (February 2005). Burawoy’s public sociology constitutes another set of answers to the questions of how we should present ourselves as scholars and writers to the people we study and the people who read our work. His arguments are worth researchers’ consideration whether or not we are sociologists. Week 12, April 18 Professional writing genres: the realist tale and its uses for theoretically driven qualitative research (p) S. Van Maanen, “Realist Tales,” from Tales of the Field (p) K. Stoddart, “Writing Sociologically: A Note on Teaching the Construction of a Qualitative Report.” Teaching Sociology 19 (1991). 8 In social science, much ethnographic and interview writing takes the form of a realist tale. This week’s reading introduces that genre of fieldwork writing. Being aware of the genre and its limits can help you make choices as a writer and avoid—or purposely invite— some trouble. Week 13, April 25 Leaving the field Charles Kurzman, “Afterword: Sharing One’s Writings with One’s Subjects,” in Burawoy et al., Ethnography Unbound, pp. 265-268. Ann Ferguson, “Afterword: Wrapping It Up,” in Burawoy et al., Ethnography Unbound, pp. 127-132. We will discuss two experiences of “leaving the field” and generate some practical ideas and tips on what to say, when, and how, if you are departing from your field sites for good. FINAL PAPER and APPENDIX DUE MAY 7, 4PM (final deadline)