CONTRACTS II OUTLINE

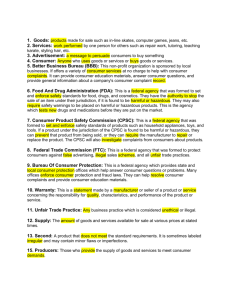

advertisement