Editor - New Zealand Freshwater Sciences Society Newsletter

advertisement

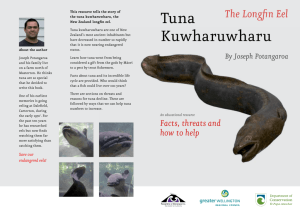

Chisholm Associates PO Box 11-014, Dunedin. Ph/Fax: 03 454-4442 Mobile 027 221-4739 e-mail: bill@chisholm.co.nz Editor - New Zealand Freshwater Sciences Society Newsletter Hannah Rainforth 204 Anzac Parade Whanganui 4500 h.rainforth@gmail.com 14th September 2009 Dear Hannah As consultant to the South Island Eel Industry Association, and a member of NZFSS, I am compelled to respond to the articles in the August NZFSS newsletter relating to banning commercial eel fishing. I have just completed the “South Island Eel Industry Association - Eel Fishery Plan for the South Island” which contains the policies and actions that the South Island commercial eel fishermen will undertake, to maintain and enhance a sustainable eel fishery. Copies of this Plan and all other reports referenced in this letter are available through emailing me at bill@chisholm.co.nz. For those who care to read this Plan, it will become immediately noticeable that commercial eel fishermen have more at stake in maintaining sustainable eel fisheries (shortfin and longfin) than anyone else in the country. The purpose of the Eel Fishery Plan is to clearly outline the measures which commercial fishermen will undertake to ensure the sustainability of their eel fishery. This includes doing considerably more than merely labelling longfin eels as “threatened”, something which the South Island Eel Industry Association strongly objects to on the grounds that it is arbitrary, unscientific and essentially futile. It would appear that Drs Joy and McEwen have based their conclusions and recommendations (to ban commercial eeling) on the results of electrofishing surveys of some lower North Island waterways (e.g. the Hutt River), and extracts from various reports. Electric fishing is known to be less than 100% effective in catching eels (e.g. Chisnall 1992), and overseas research frequently reports that eels are the most difficult fish species to catch using electric fishing (e.g. Beaumont et al 2002). Glass eels and elvers can be damaged by electric fishing. Repeat surveys may find fewer juvenile eels because they will avoid further damage by burrowing deeper into the substrate. Consequently, I have serious doubts that repeated electric fishing surveys can provide measures of juvenile eel populations with any degree of accuracy. I agree that elver recruitment monitoring at hydro dams has not been accurate, despite indications that eel recruitment trends have been stable or increasing at most sites for the last 8 years. Sampling methods have changed over this time (i.e. become more efficient at catching elvers), and longfin eels are known to have naturally variable annual recruitment. However, given the potential of this method to provide accurate long-term recruitment data, I believe that it should continue. A second method of assessing eel populations is currently available; “catch-per-uniteffort” (CPUE). Records of eel catches per net-night have been taken from commercial fishermen since before the Quota Management System was brought in. These records are analysed and compared with previous years to provide a model of eel populations over time. The methodology and latest results of this work (funded by commercial fishermen) is available in Beentjes and Dunn (2008). The latest CPUE analyses (Beentjes and Dunn 2008) indicate that eel populations are either stable or increasing in all Quota Management Areas in the South Island. This is hardly surprising, as Graynoth et al (2008) found that 49% of longfin eel stocks are in reserves or in small streams that are unlikely to be fished. This excludes those waterways upstream of hydro dams. So, if nearly half the waterways are unfished, what then caused the massive decline in longfin eel populations, and what are the threats in the future? Graynoth et al (2008) conclude that hydro dams have reduced eel access to waters that could support over 6000 tonnes of longfin eels. The average annual commercial longfin harvest, since the inception of the Quota Management System in 2000, is approximately 266 tonnes. Given the estimated current national stocks of longfins at 12,000 tonnes (Graynoth et al 2008), and an average annual commercial harvest of 266 tonnes, we can see that the real problem lies with the missing 6000 tonnes of longfins caused by hydro dams. Therefore, the decline in longfin eel populations over the last 40 years is likely to have been caused by exclusion from their habitat by hydro dams. Add the massive disruption of their habitat through land development and water abstraction, and the real threats to longfin eels start to clarify. The commercial eel fishery has correspondingly reduced as a result of these impacts; but to blame commercial fishing as a principal agent of decline is to misidentify the real threats to the fishery. Misidentified threats are a triple tragedy for conservation because: 1. The problem does not go away 2. Someone or something else suffers for the sins of others (in this case, commercial fishermen) 3. The resources spent trying to fix the problem are wasted, and could have been spent elsewhere to better effect. It would be easy to make glib statements such as “every time you switch the light on you are contributing to the problem”. However, the present threat to longfin eels is that more hydro dams are being proposed on large rivers with unfished catchments such as the Matiri, Mokihinui and Hurunui Rivers – all which contain high populations of large longfin eels. Drs Joy and McEwen would do well to divert their well-intentioned efforts away from banning commercial eel fishing and towards new hydro dams, water abstraction schemes and water quality issues. By destroying the sustainable commercial eel fishery they would be destroying the very people with the most to contribute towards these efforts. Furthermore, statements that the “inability” of commercial fishermen to catch their quota provides evidence of declining eel stocks are misguided. Commercial eel fishermen do not regard their quota as a catch “target”, for the very good reason that there is no point in catching eels if their commercial return is limited. Landed values of eels varied over the past 8 years, causing a lower take in some years, in those areas where commercial eeling is marginal. Other factors governing the take of eels can include weather conditions (e.g. floods, drought etc), fuel prices, and the full range of human-induced issues such as access, water quality and water quantity. I suggest Drs Joy and McEwen read the Eel Fishery Plan for the South Island, undertake a more detailed review of the scientific literature and consider the risks of misidentified threats before they continue with their crusade against commercial eel fishers. Perhaps they could even be persuaded to assist the South Island Eel Industry Association in our ongoing efforts to maintain sustainable eel fisheries in New Zealand? Yours faithfully W.P. Chisholm CHISHOLM ASSOCIATES References: Beaumont, W. R. C.; Taylor, A. A. L.; Lee M. J.; Welton J. S. 2002. Guidelines for Electric Fishing Best Practice. Environment Agency R&D Dissemination Centre WRc, Frankland Road, Swindon, Wilts. R&D Technical Report W2-054/TR. Beentjes, M.P.; Dunn, A. (2008). CPUE analyses of the South Island commercial freshwater eel fishery, 1990–91 to 2005–06. New Zealand Fisheries Assessment Report 2007/08 Chisholm Associates 2009. South Island Eel Industry Association - Eel Fishery Plan for the South Island. 63pp. Chisnall, B.L, 1994. An unexploited mixed species eel stock (Anguilla australis and A. dieffenbachii) in a Waikato pastoral stream, and its modification by fishing pressure. Conservation Advisory Science Notes No. 69, Department of Conservation, Wellington. 9p. Graynoth, E.; Jellyman, D.J.; Bonnett, M. (2008). Spawning escapement of female longfin eels. New Zealand Fisheries Assessment Report 2008/7. 57 p.