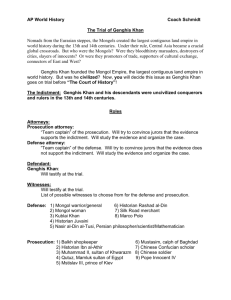

Genghis Khan

advertisement

Genghis Khan: Liberal Philosopher King? Sure, he butchered thousands. But the maligned Mongolian leader may have done as much for religious freedom as Thomas Jefferson. By Stephen Healey In the hilariously bad 1956 film, The Conqueror, John Wayne played Genghis Khan in what one critic called “history’s most improbable piece of casting unless Mickey Rooney were to play Jesus in ‘King of Kings.’” Wayne taped his eyes back to look more Asian, and he chewed up the scenery wearing a Fu Manchu moustache and spouting goofy lines like, “I believe this Tartar woman is for me. My blood says take her!” It’s hardly shocking that the Duke portrayed the visionary Mongol leader as an “oriental cowboy,” as he called him. But it is startling to consider that Western history hasn’t been much kinder to Genghis Khan. Ever since the Enlightenment, we’ve remembered the great khan as little more than a barbarian on horseback, a ruthless leader who brutally conquered and plundered most of the civilized world. Author Jack Weatherford hopes to dispel this image. In his superb book, Genghis Khan and the Making of the Modern World, Weatherford presents the 13th century conqueror as a progressive and innovative ruler who not only established international law but subordinated his own power to it. He promoted social tolerance and humanitarian values, outlawing torture, abolishing the sale of women, granting diplomatic immunity, and establishing free trade. He even built schools and championed literacy (thanks to Genghis Khan, Mongolia today has a higher literacy rate than the United States). Genghis Kahn’s contributions to Western civilization can hardly be overstated. His trade routes introduced to Europe technologies such as printing, the cannon, compass, and the abacus, as well as Mongol products like tea, lemons, carrots, playing cards, rugs, and pants. The Mongols also developed the first international postal system and paper currency. True, Genghis Khan subjugated more lands and people than anyone else in history. Using rapid siege and attack warfare that inspired the German blitzkrieg, Genghis Khan conquered more nations in 25 years than the Romans did in 400. But he extended and sustained his empire by exercising shrewd diplomacy (and wily propaganda) as well as military might. By winning over opponents with his considerable charisma, by marrying and adopting children for political purposes, and by rewarding loyalty and punishing dissent, Genghis Khan accomplished what no one had dreamed possible—he overcame 10,000 years of fierce tribal warfare to unify Mongolia. The khan and his successors ruled their empire so wisely, and so benevolently, that an age of unprecedented peace and open trade flourished over the next 150 years. Perhaps the greatest key to his success—and the biggest surprise to emerge from Weatherford’s book—was that Genghis Khan was a deeply spiritual man who established laws protecting religious freedom. Unlike most other great conquerors, Genghis Khan did not force his religion on the nations he vanquished. He believed that to conquer a nation, one had to conquer the hearts of its people, and he achieved this by allowing them to worship any deity, and adhere to any scripture, they wanted. And because his empire included every religion, from Buddhism and Christianity to Judaism, Manichaeanism and Islam, each of which claimed to be the one true faith, he hoped to minimize the religious strife he’d seen divide nations. Genghis Khan even promoted all faiths, exempting religious leaders and institutions from taxation. He wasn’t merely trying to keep the peace; he believed that every religion had something significant to offer. “Just as God gave different fingers to the hand,” said his grandson, Mongke Khan, explaining Mongol religious toleration, “so has He given different ways to men.” Granted, Genghis was no Mahatma Ghandi. Indeed, at times he resembles a certain hawkish evangelical world leader today, as when he instilled fear in his enemies by declaring, “I am an instrument of the wrath of heaven!” A devout shamanist, Genghis Khan believed that his close standing with the divine helped him to win wars. He had often “felt the presence and heard the voice of God speaking directly to him in the vast open air of the mountains in his homeland,” writes Weatherford, “and by following those words, he had become the conqueror of great cities and huge nations.” Before engaging in battle, Genghis Khan would sometimes pray for days, alone on a mountain, seeking the guidance of the Eternal Blue Sky. When presenting a case for war to his supernatural guardians, he’d recount the generations of grievances the Mongols held against an enemy. He’d explain why war was necessary, a last resort initiated by his enemy and not sought by him or his people. At other times he’d offer elaborate prayers of thanks for a victory, removing his hat and sash, a gesture that rendered him, the most powerful man on earth, powerless before the gods. The khan’s undeserved bad rap, Weatherford shows, traces back to 18th century European anti-Asian sentiment. Though Renaissance writers praised Genghis Khan’s virtues extravagantly, Enlightenment thinkers blamed him and the Mongols for Europe’s most detestable qualities. In a play intended to attack the French king, Voltaire, perhaps fearing for his head, substituted Genghis Khan for his nation’s cruel and ignorant ruler. He described the khan as a “wild Scythian soldier bred to arms” and his people as “wild sons of rapine, who live in tents, in chariots, and in fields.” They “detest our arts, our customs, and our laws,” Voltaire wrote, “and therefore mean to change them all. In the 19th and early 20th centuries, pseudo-Darwinian scientists linked criminal behavior biologically to the Mongols, and eugenicists coined the term “Mongoloid” to describe retarded children, who they believed had inherited degraded Mongol genes through centuries of interbreeding. Genghis Khan’s true legacy wasn’t accessible until the fall of the Soviet Union. Once Mongolia opened in 1990, Jack Weatherford was among the first scholars to visit and begin peeling away the misperceptions. Among these was the notion that Genghis Khan was a reprobate, a hedonist who collected women and luxuries as the spoils of war. Although the khan was polygamous and had accumulated tremendous power and wealth, Weatherford shows that he possessed a sober manner and was devoted to leading a simple life. “I hate luxury,” said Genghis Khan, summarizing his ideals, and “I exercise moderation.” Raising his sons to become rulers, he insisted that the key to leadership was self-control, and he cautioned them against pursuing a “‘colorful’ life with material frivolities and wasteful pleasures.” Indeed, Genghis Khan’s paternal advice offers a timeless wisdom to our own age of unchecked consumption. He claimed that the fall of his enemies had more to do with their weaknesses than his own superior strengths, saying that God had condemned the civilizations around him because of their “haughtiness and their extravagant luxury.” Materialism, said the man who had conquered the world, leads the soul astray. “It will be easy,” he warned his sons, “to forget your vision and purpose once you have fine clothes, fast horses, and beautiful women.” And then, he added, “you will be no better than a slave, and you will surely lose everything.”