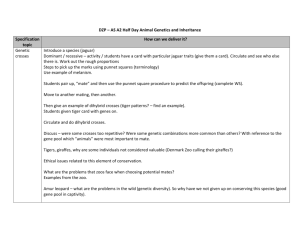

Human-Tiger Conflict Thesis

advertisement