Weng 1 name romantic. This desire for romantic names is further

advertisement

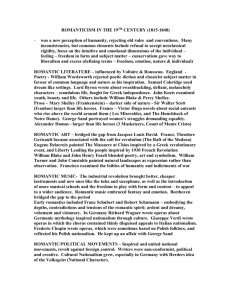

Weng 1 name romantic. This desire for romantic names is further satisfied in her composition of a romance, because the names of the hero and heroines are Bertram De Vere, Cordelia Montmorency, and Geraldine Seymour. One meaning of the word romantic in Merriam-Webster’s Collegiate Dictionary (MWCD, 11th ed) is “marked by the imaginative or emotional appeal of what is heroic, adventurous, remote, mysterious, or idealized”, which I think is what Montgomery means when she depicts Anne as a person with a predilection for these remote and exotic names. According to MWCD, romantic comes from the French word “romantique”, developing from “romant” (meaning “romance”), the word itself from Old French “romanz”, while romance is from Middle English “romauns”, developing from Ancient French “romanz”. Thus romantic and romance have a close relation in etymology. As a literary genre, medieval romance, or chivalric romance, is a “narrative genre which developed in twelfth-century France”, representing “a courtly and chivalric age, often one of highly developed manners and civility”, and “it delights in wonders and marvels” (A Glossary 24). Anne’s impressive romantic activities are the most charming parts in the novel and have effectively proved her romantic trait. Among these episodes most are related to connotations or/and denotations of romance. One of Anne’s wishes in life is “to be a trained nurse and go with the Red Crosses to the field of battle as a messenger of mercy” (Montgomery 149), but it is still secondary to the aim of being a foreign missionary. Both the two dreams involve a wandering life, the adventurous feature of romance. In the farewell scene with Weng 2 Diana, Anne asks for one lock of Diana’s hair to treasure and she tells Marilla that she is going to sew it up in a little bag and wear it around her neck. She even indulges herself in an imagination that the lock of hair should be buried with her for she believes she will not live long. The action of preserving a partner’s hair and the imagined plot which adds a tragic air to the former are obviously an imitation from romances, half funny and half pompous. However the fantasy of “the Haunted Wood” is quite another kind to be romantic, because Anne imagines a white lady (who “wrings her hands and utters wailing cries”, and whose appearance is an omen of a death in some family), a ghost of a little murdered child (who “creeps up behind you and lays its cold fingers on your hand”), and a headless man (who “stalks up and down the path and skeletons glower at you between the boughs”) (Montgomery 128-129) into this quite ordinary wood. This fancy is even more Gothic than romantic. We notice that Montgomery adds the title “A Good Imagination Gone Wrong” to this chapter which shows some criticism on Anne. In fact Marilla cures her of being too romantic by forcing her to go through the wood in the evening when the ghosts are supposed to appear. However, we do admire her talent in the composition of a romance titled “The Jealous Rival; or, in Death Not Divided”. She consults her friend Ruby Gillis about the proprieties of a proposal for her hero and heroine, and is dissatisfied with Ruby’s description of a very practical and common one. So she let her hero propose to his lover in the manner of a chivalrous knight. And the heroine accepts him “in a speech a page long” (Montgomery 162). Anne insists that the ending of the story should be Weng 3 tragic—the lovers are both drowned and the antagonist, the rival turns mad and is shut up in a convent, because she believes that a tragic ending is more romantic than a happy one, which shows her aesthetic taste. Anne’s last memorable romantic activity is the play-acting, in which she acts the main character Elaine. With the fanciful costumes and props, Anne is to be a dead lily maid drifting down in a flat to the lower headland, where she is to be received by “Lancelot”, “Guinevere”, and the “King”. But her enjoyment of such a romantic situation ends almost in a very tragic way, because the crack in the bottom makes the flat begin to sink while floating. Fortunately she is rescued by Gilbert Blythe in time, who is then her unforgivable enemy. Early in the novel Anne exclaims that “[i]t would have been such a romantic experience to have been nearly drowned” (Montgomery 81); when this wish is dutifully satisfied she feels nothing romantic at all. This incident further cures her romantic tendency. Actually, as Anne grows up, she becomes a standard good girl, less interesting and more common. This is perhaps what we call the cost of being mature. To sum up, we find that Montgomery’s concept of romantic is quite rich. It involves the most important characteristics of the Romantic Period in English literature—love of nature, poetic expressions, and an emphasis on imagination. Though in the above exposition of the term romantic I do not expand much on imagination, we all know that Anne’s creations and imitations of poetic expressions, her preference for legendary and exotic names, and her romantic actions are all based on her imagination. But the meanings of Montgomery’s romantic have gone beyond Weng 4 those that mark the features of the Romantic Period; her romantic on many occasions defines itself in the range of romance, or even Gothic novels. We can not fail to detect some Gothic elements in Anne’s composition of that romance and the fancied stories of “the Haunted Wood”. However, not only romantic poetry is related to medieval romance, as is proved by works of Coleridge and Keats, but also Gothic novels (Generally speaking, they are in the scope of romantic novels), with magic and supernatural phenomenon, are “an attempt to blend the two kinds of romance: the ancient and the modern” (Lewis xii), the former definitely referring to medieval romance. Therefore, it is proper to say that Montgomery has well probed into the concept of romantic in its abundant connotations and denotations formed in a long literary tradition. Weng 5 Works Cited Abrams, M. H. A Glossary of Literary Terms. New York: Holt, 1988. Abrams, M. H., and Jack Stillinger. “The Romantic Period.” The Norton Anthology of English Literature. 6th ed. Ed. M. H Abrams. New York: Norton, 1996. Coleridge, Samuel T. “Biographia Literaria.” The Norton Anthology of English Literature. 6th ed. Ed. M. H Abrams. New York: Norton, 1996. Lewis, W. S. Introduction. The Castle of Otranto. By W. S. Lewis. London: Oxford UP, 1964. xii. Montgomery, L. M. Anne of Green Gables. 1985. New Jersey: Gramercy-Random, 1986.