TOPIC 2B Life and death in a changing society This topic will deliver

advertisement

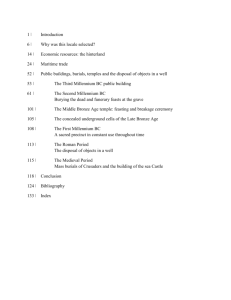

TOPIC 2B Life and death in a changing society This topic will deliver the following learning objectives: 1. to understand the variety of settlements and mortuary customs in the Yayoi and Kofun periods; 2. to debate similarities and differences in settlements and burials in the Yayoi and Kofun periods; 3. to understand how we can use archaeological materials to explain the nature of society. HYPERLINK TO BACKGROUND INFORMATION Kofun Chiefs and commoners HYPERLINK TO TEACHING MATERIALS Enclosed settlements and mansions Buried elites and kofun burial mounds HYPERLINK TO STUDENT ACTIVITIES Students can be asked: how can we understand changes in settlements from the Yayoi to Kofun periods? how can we interpret changes in burials from the Yayoi to Kofun perio ds? BACKGROUND INFORMATION Kofun A kofun is a monumental burial structure in which the burial chamber is surrounded by a large mound of earth. The largest were up to 400 metres long, the smallest only 10 metres across. Some kofun were also surrounded by one, two or even three water-filled moats. They were built after 250 AD. The burials in the chamber were often accompanied by grave goods. The size of the mound and the richness of the goods tell us that these were the burials of the social elite of the time. The shape of the mound varies. Some kofun are square (hofun), some circular (empun) and other have a keyhole shape (zempo-koen-fun in Japanese) with a round mound joined to a square flared section. The mounds were sometimes covered with sepcial cladding stones (fukiishi); either for decoration to prevent the mound from collapsing. Larger keyhole mounds would often have clay figures (haniwa) placed on the flat upper surfaces of the mound. This mound type first appeared in the Yamato region in the south-eastern part of the Nara basin. Chiefs and commoners Many archaeologists believe that residences of the community were separated from the residences of the chiefs. These may be separate farms in the area around the residence or in separate parts of the same settlement. Kofun burial mounds would be some distance away from the settlements. TEACHING MATERIALS 01 Enclosed settlements and mansions There are many different kinds of settlement. Detailed excavation reveals many of the details of their structure and the functions of their buildings. The following teaching materials can be used to answer the question How can we understand changes in settlements from the Yayoi to Kofun periods? Figure 01 Middle Yayoi settlement of Otsuka, Kanagawa prefecture A single ditch enclosed an area of 200 x 130 metres, and contained 115 pit dwellings and 10 post built buildings. The post-built structures may be storage facilities. There is no distinctive differentiation of the leader’s house from the rest. Figure 02 Middle Yayoi settlement of Otsuka and the Saikachido cemetery, Kanagawa prefecture The Otsuka enclosed settlement and Saikachi cemetery with square shaped moated burials were located side-by-side on the same hill. 25 square-shaped moated burials were excavated and more burials would exist outside of excavation area. The burials are surrounded by moats of between 6 and 12 metres across. All the burials are of roughly similar size. A single pit burial is set in the centre of each square and often additional burials are in the bottom of the moats. It is thought that each square moated burial includes member of the same family. Figure 03 Plans of Yoshinogari, Fukuoka prefecture in Kyushu island Yoshinogari settlement began in the Early Yayoi, and by the Late Yayo i had developed to cover 40 hectares. An outer moat 8 metres wide and 4 metres deep enclosed the whole hillside. The hill was 1000 metres from north to south and 600 metres from east to west. The residential area inside the moat included a variety of facilities. These were arranged in zones for dwelling, for post-built storage and for burials. Figure 04 Reconstruction of Yoshinogari, Fukuoka prefecture in Kyushu island Three different qualities can be seen in the residential zones. The northern enclosed zo ne shown here has post-built structures, including a large building of 13 metres square with 16 posts. Buildings with four flared corners are reconstructed as watch -towers. In this area was found a bronze halberd. This zone was thought to be a ritual space or the residence of a chief and his household. Figure 05 Excavation of Yoshinogari, Fukuoka prefecture in Kyushu island The southern enclosed area had mainly square pit dwellings. Post-built buildings with two flared corners in the south were probably watch-towers. In the the moats, four bronze mirrors were found. This zone is thought to be a residential area for the elites. Around 60 square pit dwelling were found, although much disturbed by farming in later periods. Other areas of pit dwellings were found to the north of the outer moat. The main storage area with around 100 post -built structures is located to the west of southern enclosed zone. Figure 06 Inner residential area at Mitsudera 1, Gunma prefecture in Kanto district (Middle Kofun period, 5t h century) An inner square area of 86 square metres was enclosed by a moat to the south and west and by natural rivers in the north and east. The moat was 3 metres deep and 30 metres wide. The soil from the moat was piled up on the residential area up to 1.5 metres thick to give it extra height. The outer slopes of the residential island were covered with stones. The outer rim of the area was surrounded by triple wooden fences. The square arena was divided into two sections; north and south. The southern section comprises some post-built buildings, a well and water apparatus. A large building of 158 square metres is thought to be a residence or office for the chief. A water apparatus with stone-flagged facilities was connected to the bridge of wooden conduit . The southern section was a ritual space for the chief and was shielded by wooden fence. Figure 07 View of the whole site of Mitsudera 1, Gunma prefecture in Kanto district (Middle Kofun period, 5th century) In the northern section, even though only the south corner was excavated, there were two pit dwellings of 5 metres square. Tsude Hiroshi thought the northern section was for household management to support the chief living in the southern section. Tatsumi Kazuhiro suggested instead that the site was site was divided into a secular north and a sacred south. Accordingly, this northern part of the site is a residence for a chief; not for ordinary villagers. F arming villages, such as Kuroimine, have been found in the area around the site, and clusters of k ofun, including three key-hole shaped mounds, are about 1 kilometre northwest of Mitsudera 1. These would be the burials of the chiefs. STUDENT ACTIVITY 01 Key question How can we understand changes in settlements from the Yayoi to Kofun periods? Secondary questions Can we classify the kinds of structures found on the sites by type of building, size and location? How do the three sites compare in their evidence for chiefs and ordinary villagers? Why might the sites, or parts of the sites, be surrounded by a moat? TEACHERS NOTES Separation of chiefs from commoners in the Yayoi and Kofun periods According to Terasawa Kaoru and Takesue Junichi, there are three types of arrangement for the residences of chiefs within their local community. Type 1: the chief lives in the settlement with the others members of the community. The leader’s house does not show distinctive differences in size or structure. Many moated enclosed settlements seem to belong this type, for example,Otsuka in Kanakawa prefecture. Type 2: the chief lives in the settlement with the other members of the community, but their house is separated by a moat, ditch, bank or fence. At Yoshinogari, there are two inner enclosed zones (north and south) separated by moats, and there is a differentiat ion in size and structure of buildings between post-built buildings in the north and a residential zone of pit dwellings. Some researchers suggest that the Ikegami-sone site might be another example of this type. Type 3: the chief lives in a mansion with large post-built buildings separated from the settlements of the community. Mansions are often enclosed squares with a moat, ditch or fence. The villagers' settlement consists of several pit dwellings, without being enclosed, and are scattered around the mansion. Mitsudera 1 is a typical mansion for chief. These types may represent a sequence of historical processes in which there was an increasing separation of the living space for ruling people from the communal living space. This shows the development of social stratification and emergence of powerful elites. The role of the moat Moat or ditches had both a utilitarian function and a symbolic role. The moat or ditch surrounding the whole residential area in the Yayoi period disappeared in the Kofun perio d. However, tensions among chiefs were still high as shown by a large amount of iron weapons and armour founded in Kofun tombs. It is hard to explain the disappearance of moats through a decrease in elite competition. Rather, the progress of social stratification led to the disappearance of community unity and a decline in enclosing communal settlements by such a moat; the moat had lost a symbolic function. The moat of Mitsudera 1 in the Kofun period would have been for defence or water management, at the same time as being a landmark to express power or sacredness. This means that a moat and ditch had different symbolic meanings at different times.It was a symbol of community unity in the Yayoi period and of sacredness of the chief in the Kofun period. Generally a moat, ditch and fence are thought of as defences. At Yoshinogari, the moat is on the inside of the bank. Is this reasonable for a defensive structure? Setting the bank inside the moat or ditch is more effective for defence, because the defenders c an fight from top of the moat. Discontinuity of settlement The large scale settlements in the Yayoi period are not ancestors of modern villages, towns or cities. There is a hiatus of settlement between the Yayoi and Kofun periods. TEACHING MATERIALS 02 Buried elites and kofun burial mounds A major feature of burials is the presence of grave goods with the bodies. These can tell us a lot about the status of the person. The following teaching materials can be used to answer the question How can we interpret changes in burials from the Yayoi to Kofun periods? Figure 08 Middle Yayoi burial mound at Yoshonogari, Fukuoka prefecture, Kyushu district The mound burial was 40 metres long north to south and 27 metres wide east to west. It was located in the northernmost part of the enclosed area next to the outer moat. It was originally over 4.5 metres high. 14 double jar burials of the Middle Yayoi period were found inside. Two pottery vessels were fitted mouth to mouth to form a coffin. Eight of the burials ha d grave goods: bronze swords and glass cylindrical beads. Figure 09 Jar burial No.1002 at Yoshonogari, Fukuoka prefecture, Kyushu district From a burial in the mound in Figure 08, there was a bronze sword (44.5 cm long) and 79 cylindrical beads made of blue glass with a large amount of red cinnabar. All burials in this mound were of adults and no jar burials of children were found. It is thought that successive chiefs were in this mound. Figure 10 Jar burials in the settlement at Yoshonogari, Fukuoka prefecture, Kyushu district About 2,500 other jar burials were found in several rows and blocks in the settlement. In contrast with burials in the mound, there were no grave goods of bronze. Instead, there were iron knives, shell bracelets and stone beads. Figure 11 Headless body from the settlement at Yoshonogari, Fukuoka prefecture, Kyushu district Some of the skeletons from the settlement had their head removed. This is assumed to be the result of warfare. Figure 12 The Nintoku-tenno-ryo Kofun in Isumi province (uppermost kofun) Huge mounds appeared in Isumi province in the Osaka bay area in the Middle Kofun period. The Nintoku-tenno-ryo Kofun of 486 metres length is the largest burial mound in Japan. Most of the monumental kofun were built in this keyhole shape, and huge mounds over 100 metres in length are concentrated in the Kinai region, including Nara and Osaka. For this reason, keyhole -shaped kofun are thought to symbolise the political power of the Yamato 'state'. Figure 13 Imashirozuka-kofun, Osaka prefecture, of the Late Kofun period (6th century) The Imashirozuka-kofun measures about 354 metres in total length, including its double moats. There is one theory that this kofun mound is the tomb of Emperor Keitai, and is described as Mishima Aino Misasagi in ancient documents. An arrangement of about 180 haniwa clay objects was found on the flared section between the two moats. They were arranged in four zones divided by palisades. The haniwa were clay models of houses, waterfowl, armoured men, a pyth oness and so on. Figure 14 A model house haniwa from Imashirozuka-kofun, Osaka prefecture, of the Late Kofun period (6th century) Figure 15 An armoured warrior haniwa from Imashirozuka-kofun, Osaka prefecture, of the Late Kofun period (6th century) Figure 16 Hotoda-hachimanzuka-kofun in the Hotada mound cluster near Mitsudera 1 An arrangement of 54 haniwa clay objects was found on a part of the inner bank between the two moats, surrounded by a border of cylindrical haniwa. There was a variety of haniwa c lay objects: people sitting on a chair, waterfowl, wild boar and so on. Figure 17 Mirrors at Kuroda kofun Mirrors decorated with images of immortals and beasts are typical grave goods in the Early Kofun period. They are found from the southern Tohoku district to Kyushu island. At Kurozuka-kofun, about 30 of this type of mirror were placed just outside of a wooden coffin in the stone chamber. STUDENT ACTIVITY 01 Key question How can we interpret changes in burials from the Yayoi to Kofun periods? Secondary questions Why did burials for elites lose become separated from the community? Why did burials for elites lose their regional differences in the Kofun period? TEACHERS NOTES Yayoi period burials At Yoshinogari, there are clear differences in grave goods between burials in the mound and in the rows. Both, however, are set inside an outer moat and near to the dwelling area, and used jar coffins. This would be a reflection of community unity. A sense of cooperation was still expressed in the spatial arrangement of burials and the form of coffins while still signalling social stratification. Jar burials for adults are a regional characteristic of Yayoi Kyushu; different from the square shaped moated burials (Hokei Shukobo) from Kansai to Kanto, such as the Saikachido site. Kofun period burials Kofun burial mounds were separated from residential areas and cemeteries of ordinary villagers. The keyhole-shape mounds as Mozu-Furuichi Kofungun and Hotoda represent the existence of powerful chiefs. The important ritual use of water is also separated from the residential area of the community and is monopolized by the chief as shown at Mitsudera 1. Terasawa has put forward the idea that structures representing of sense of unity, such as the moat and central building , became an obstacle to establishing a new hierarchy. This shows that social stratification was developing and that chiefs as a representatives of the community in the Yayoi period were instead becoming authorities over local society, and were at the same time trying to achieve more political power. The widespread sharing a similar way of burial for its chiefs reflects the desire of local chiefs to enhance their political power by aligning themselves the Yamato 'state' in the Kansai district. Comparison between Imashiroduka in Osaka and Hotoda-hachimanyama in Gunma provides a good example of similarity in using keyhole mounds and haniwa clay objects.