Forms and Particulars (handout)

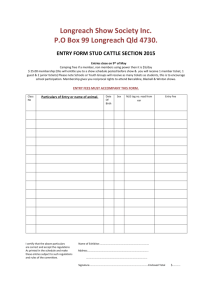

advertisement

PLATO: FORMS AND PARTICULARS Some examples of particulars: Socrates, George Washington, Elvis Presley, my copy of Ten Theories, Gary Ransdell’s newest car, my cat Mocha, the pen in my pocket, the swivel chair in my office, the smallest piece of chalk in this classroom, the imaginary picture of Socrates I have in my mind this morning at 8:35 a.m., my reflection in the mirror at 7 a.m. today. The sequence of letters printed right here on this sheet of paper A R I S T O T E L E S. Some Platonic Forms: Beauty as such (the Beautiful itself), Virtue as such, Justice as such (the Just itself), Goodness (aka the Good itself), Piety (the Pious itself) For Plato, moral goodness and true happiness are impossible without wisdom. Political wellbeing is impossible for a state whose rulers lack wisdom. Wisdom is impossible without general knowledge. General knowledge is impossible without universal truths. (The model here is mathematics, of which geometry was most developed in Plato’s time.) Universal truths are based on realities of a special kind, e.g., Justice, Beauty, Wisdom, Virtue (which are similar in some ways to mathematical objects line, plane, triangle). These special realities are unchanging; when you know something, what you know does not change. They are not particular realities. Material things are particulars existing in space and time (“this, here, now”; “that, there, at that time”). Particulars come into being and pass away; they are subject to change. Particulars can be sensed by bodily organs or remembered in sense memory or imagined in imagination modeled on sense memory. We can understand the special realities; so we can say they are intelligible. Intelligibility and sensibility (visibility, audibility, etc.) are distinct from each other. Particular things often share common qualities, e.g., red things share redness. Particular things often express the same nature or essence, e.g., human beings express human nature. When we talk about the universal natures or essences of things, we are talking about the special realities Plato calls Forms or Ideas. General words, e.g., BEAUTY, JUSTICE, WISDOM, VIRTUE often refer to Forms. When we attribute such qualities or natures to particulars, we are relating the particulars to the Forms. When I say, “Socrates is wise,” I am saying that this particular human being “shares in” or expresses the Form Wisdom. Dr. Jan Garrett, September 19, 2011 PARTICULARS located in space and time come into being and pass away perceptible by the senses many of the same type of them we have perception and experience they lie between being and nonbeing they can trigger reflection about Forms we can evaluate them as good or bad, right or wrong, beautiful or ugly they are referents of proper names, demonstrative pronouns (Barack Obama, this [book] FORMS not located in space or time eternal (M) intelligible by the mind (E) Unique those acquainted with them KNOW (E); those who know can provide an adequate definition (“account”) and are able to teach ... they possess full reality (M) they define the nature of particulars they provide standards of conduct and evaluation (Mo) They are referents of general terms that have a fixed meaning (“Beauty,” “Goodness,” etc.) (S) M= metaphysical function of the Forms. Metaphysics addresses the question “what is real?” For Plato and Aristotle, things that are most real have explanatory power). S= semantic function of the Forms. Semantics addresses the question “how do words or phrases take on meaning?” E=epistemological function of the Forms. Epistemology addresses the question “what can we really know? (Philosophers often distinguish knowledge from mere opinion about or familiarity with some subject.) Mo=moral function of the Forms. Ethics, which studies morality, relates to the question of “what should we do?” A related function of certain Forms is aesthetic: “what would things be like if they were beautiful?” Dr. Garrett, September 23, 2011