UCMUN 2013 United Nations Environmental Programme

advertisement

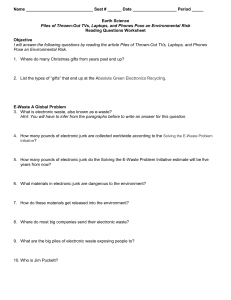

UCMUN 2013 United Nations Environmental Programme Introductory Letter Welcome to the 2013 UCMUN United Nations Environmental Programme! I am Farah Gazi and I will be your Director this year. I am very excited to be working with you all and am looking forward to a great conference. We, as the human race, are bounding forward with our technological advances and innovation. This fast pace is what makes us great, allowing us to travel great distances, cure diseases, and overcome the greatest of obstacles. Yet, it is also important to explore the consequences of our advances and to become more proactive about the innovations we create. Our topics this year will allow us to do just that. They are ‘Implications of Electronic Waste’ and ‘Reducing Mercury Emissions’, which I hope are relevant to and will engage you all. I am currently a sophomore honors student majoring in Physiology and Neurobiology. For me, Model UN is a great way to delve into the social and political consequences of the hard sciences that I explore in class. Outside of academics, I love to read, hang out with friends, and explore different places. Travelling and multiculturalism have been a part of my childhood: I am from Oklahoma and Bangladesh but grew up in the Middle East. I have even participated in Model UN in Kuwait. My desire is for you all is to be able to take away from this conference as much as I hope to myself, challenging yourselves and broadening your horizons. In the meantime, please feel free to contact me with any questions and concerns via email. I look forward to meeting all of you! Farah Gazi UCMUN 2013 Director of the United Nations Environmental Programme Email: farah.gazi@uconn.edu UCMUN 2013 United Nations Environmental Programme Committee History Committee History 15 December, 1972 marks the creation of the United Nations Environmental Programme. The Conference on the Human Environment held in Sweden at the time proposed a body of the United Nations dedicated solely to tackling issues concerning the environment. It is becoming increasingly evident that human development and the environment have a close relationship. The UNEP consists of three major components, the Governing Council, the Secretariat, and an Environmental Fund. The Governing Council is a set of 58 nations, elected by the General Assembly for a four-year term, which sets the priorities and budget for the UNEP. The Secretariat, based in Nairobi, Kenya, focuses and coordinates the action taken by the committee. Lastly, the Environmental Fund is a voluntary resource that is supplemented by other funds to help finance the committee’s work. Since its recent beginnings, the UNEP has addressed a number of major issues. Much of the focus lies in collaborating and creating international goals that better align with the idea of sustainable development. Some of these actions and addresses include: 1985: Vienna Convention for the Protection of the Ozone Layer 1989: Basel Convention on the Trans-boundary Movement of Hazardous Wastes 1995: Global Programme of Action (GPA) launched to protect marine environment from landbased sources of pollution 2000: Millennium Declaration – environmental sustainability listed as one of eight Millennium Development 2005: Kyoto Protocol on Climate Change enters into force 2005: 2005 World Summit agrees to explore a more coherent institutional framework for international environmental governance 2005: Bali Strategic Plan for Technology Support and Capacity Building adopted by UNEP Governing Council mandating national level support to developing countries UCMUN 2013 United Nations Environmental Programme Committee History Works Cited United Nations. United Nations Environmental Programme. UNEP Organization Profile. N.p., n.d . Web. UCMUN 2013 United Nations Environmental Programme Committee Simulation Committee Simulation Role of the Delegate Delegates are the center of debate; without them, the UNEP cannot function. They are expected to participate in debate, negotiate with others, and accurately represent the views of his/her nation. Delegates are here to simulate reality: to best align with their respective nation’s policy in order to pave way for advancements in international action and policy through negotiations with other nations. The goal of the committee is to pass at least one resolution addressing the topics at had. All this requires that a delegate be adequately prepared with research on the topics, their implications, his/her nation’s standpoint, and more. It must be kept in mind that often times, especially regarding environmental law, there may be a discrepancy between action and viewpoint. This may be a result of finances, alliances, or even domestic political conditions. Well-done research will help elucidate the complex relationship between these factors and formal policy; a good delegate will take into considerations this complexity when debating and agreeing to negotiations. With solid background information, delegates should be a part of an engaging and vivacious debate. Delegates are expected to abide by the rules of parliamentary procedure in both formal and informal debate, and by the rules of the conference when not in debate. It is requested that all be respectful of each other and the serious issues at hand. Lastly, these rules are here to maintain order and respect. A delegate is encouraged to think creatively and have fun. Role of the Dais The Director and Assistant Director(s) comprise the Dais. Its role is to moderate debate, set rules for debate, and encourage participation. This will be done through maintenance of a speaker’s list during formal debate. The Dais will formally set debate, voting procedure, and end debate. UCMUN 2013 United Nations Environmental Programme Topic A: E-Waste Introduction Electronics are an integral part of modern society. To keep up with demands, new gadgets are being designed and created all the time as old ones become obsolete. With this fast-paced use and disuse, much waste is produced. Although a single definition does not exist, electronic waste, or e-waste can be any abandoned or obsolete electric or electronic products, and is one of the most rapidly growing waste sectors (E-WASTE: The Exploding Global Electronic Waste Crisis 2). Because the technological advances of today are fairly new, regulation of waste is not properly addressed or enforced in many nations. Most e-waste from developed nations is imported into developing nations such as India. In developing nations, metal and other materials can be salvaged from used electronics and workers salvage these valuables using unregulated and oftentimes hazardous protocol. These workers do not take proper precautions and often contract heavy metal poisoning. Furthermore, most un-salvaged products end up in landfills and can contaminate land, air and water. Acid used in the process is dumped in streams and landfills and thus harm the environment. Overall, the process of extrapolating valuable elements (gold, copper, silver, plastic) is not sustainable. Although some nations, both developed and developing, have policies regarding e-waste, these are easily circumvented. Other nations have not created any policies whatsoever. This year in the UNEP, we will attempt to further explore this exciting sector of environmental policy. We will look into how nations can address the problem of e-waste both within their borders and together with the international community. Topic History The Koko Row in 1987 “sparked international outrage” when 8,000 barrels of waste were dumped in Koko, a village in Nigeria, by a European importer (“A Cadmium Lining”). In the next UCMUN 2013 United Nations Environmental Programme Topic A: E-Waste three years, many more incidents brought the problem of general waste dumping to the headlines. This included Nigeria’s $1m fine on importers from Tilbury, UK that attempted to bring “two 12metre containers full of defunct televisions, computers, microwaves and stereos” (“A Cadmium Lining”). These important events among others brought attention to the increasingly important sector of e-waste. The Basel Convention was passed in 1989 following the Koko row to regulate waste dumping in developing countries. It was updated in October 2011 to include a general ban on export of hazardous waste including electronic scrap. Although the convention works to reduce illegal e-waste dumping and produce more sustainable and economic ways of doing so, criticism also exists: “[lesser developed countries] already produce a quarter of the world’s e-waste pile; they could overtake rich ones as early as 2018. Choking off the trade [through Basel Convention] will not stop the acid cauldrons bubbling” (“A Cadmium Lining”). The author here refers to the plentiful e-waste that is produced within the borders of the developed nations themselves. Furthermore, nations such as Afghanistan, Haiti and the USA have yet to ratify the treaty ("International Legislation & Policy"). In the following sections, we take a look at how developing and developed nations plays a role in the problem of e-waste. Despite international efforts, current regulations and enforcement are not enough to stop the transportation of Figure 1: Recycling policies state by state in the USA. Although no federal law targets e-waste disposal, state laws are starting to address the problem. Much work is yet to be done to complete these policies, enforce them, and inform and encourage consumers to use them. Source: Wirfs-Brock. UCMUN 2013 United Nations Environmental Programme Topic A: E-Waste and counter the negative heath, environmental, and economic effects of e-waste. Part of the problem lies in developed nations that do not have or enforce laws for proper disposal or recycling. Developed nations that have access to high tech salvation methods and technology can save up to 95 percent of the metals from old products, such as the plants in Belgium, Canada, Germany, Japan and Sweden that employ an integrated smelting and refining technique (Schluep et al. 6). However, these are very costly to maintain, and most used electronic material does not end up in these plants because regulations for recycling are not set (Schluep et al. 6). In the US, for example, there are no federal laws for proper disposal and recycling and thus the majority of the population disposes Figure 2 (above): Some routes of e-waste dumping. The USA and EU are big known sources of e-waste while India and China are known importers. Source: "The Bane of Hi-tech Waste". of used electronics by simply throwing them in the trash. Furthermore, consumers are not aware of the drastic effects of improper e-waste disposal and of proper disposal protocol. The waste ends up in landfills or in electronic waste grounds that are eventually shipped outside of the country. The trend of exporting e-waste to developing nations emerged in the 1990s when recycling systems in developed nations such as the EU, Japan and the USA could not deal with the large quantity of e-waste that was being produced within their borders ("Where Does E-waste End Up?"). Developing nations provide cheap labor and lack laws that protect workers or the environment. The UCMUN 2013 United Nations Environmental Programme Topic A: E-Waste process of recycling e-waste is cheaper as well since not many regulations limit how it is done. For example, glass-to-glass recycling of computer monitors is ten times more expensive in the USA than it is in China ("Where Does E-waste End Up?"). Demands for e-waste grew further in developing nations, especially in Asia, when Figure 3 (left): Specific routes of ewaste dumping in Southeast Asia. Ewaste can originate from Europe, North America, or even within Asian nations. Source: "Where Does Ewaste End Up?" valuable substances such as copper, iron, silicon, nickel and gold could be salvaged and sold for money in the process ("Where Does E-waste End Up?"). For instance, the average cellular phone can yield 19 percent copper and eight percent iron ("Where Does Ewaste End Up?"). Exportation is carried out through cargo ships that transport used electronics with the intention of selling and distributing these used items to the less privileged. However, most of these electronics are not reusable and are actually sold and recycled. This is done by disposal companies and even organized crime groups ("Where Does E-waste End Up?"). The 1992 Basel Convention controls shipment and transportation of hazardous materials over international borders. However, illegal transportation is high. This may be due to the fact that many nations have yet to ratify the treaty and others do not strictly enforce the rules ("International Legislation & Policy"). UCMUN 2013 United Nations Environmental Programme Topic A: E-Waste Developing Nations The waste is shipped to developing nations where there are no proper disposal methods, regulations on import, or sustainable and safe recycling methods. Two of the biggest dumping grounds are China and India. Recycling in these nations provides a source of income and trade for the less privileged. Workers are paid by some organized companies for their labor or can directly sell extrapolated metals and valuables to buyers. Although importation is banned in these nations, ships illegally bring in e-waste under disguise of re-usable electronics or other shipments (Walsh). Case Study: India “25,000 workers are employed at scrap yards in Delhi alone, where 10-20000 tonnes of ewaste is handled each year, 25 percent of this being computers. Other e-waste scrap yards have been found in Meerut, Ferozabad, Chennai, Bangalore and Mumbai.” ("Where Does E-waste End Up?"). The biggest of these scrap markets is in Seelampur, a city near New Delhi. “India generate[s] 146,800 tons of e-waste in 2005. 50,000 tons of waste is imported a year despite [a national] ban. According to activists, importers have long exploited a loophole in the bans that allows for imports of used electronics as donations” ("Where Does E-waste End Up?"). The e-waste sector in India is highly informal and unregulated. Over 95 percent of the e-waste source: Howard. that is handled is done so illegally in unorganized facilities. The biggest challenge in combating the e-waste issue is organizing this sector, which currently runs on consumers being paid for their UCMUN 2013 United Nations Environmental Programme Topic A: E-Waste waste and recyclers. (Kishore and Kishore). However, the government is working to create plants that will utilize better and safer practices to recycling and has even “signed a $90 million project with the World Bank” (Walsh). Further efforts are being initiated by the Ministry of Environment and Forests which is working with NGOs to outline regulations on e-waste to supplement those that were set in 2007 by CPCB India. These are based on the idea that the manufacturer is responsible for proper disposal its products (Kishore and Kishore). Dismantling Practices, Health Risks and Human Rights Since the e-waste sector is mostly unorganized, much of the specific practices employed by workers are unknown. However, it is known that the average worker is paid from Rs. 5 to 10 for the dismantling of one computer piece (Kishore and Kishore). Practices pose many health and environmental risks. Use of proper “wastewater treatment facilities, exhaust-waste gas treatment, and personal health protection equipment” is nonexistent (Kishore and Kishore). Metals are extracted in open acid baths which release toxins to the environment such as “dioxins, heavy metals, lead, cadmium, mercury and brominated flame retardants (BFRs)” (Kishore and Kishore). These pollutants contaminate nearby water and soil. Furthermore, workers do not wear protective gear and expose themselves to dangerous chemicals. This exposure can lead to asthma, skin disease, brain and kidney damage and hormonal imbalances especially in children and even unborn babies of pregnant workers. Recycling workers are not informed about these risks and receive neither training in their practices nor any safety precautions. UCMUN 2013 United Nations Environmental Programme Topic A: E-Waste As mentioned previously, pay is very little. Workers are often times children trying to earn a living. Recycling provides livelihood for many under-privileged people in India. However, it can also destroy their livelihood through health and physical risks. UNEP’s Role The UNEP has been playing a big role helping create and implement e-waste policy in nations worldwide. It published the “E-Waste Management Manual”, outlining safe techniques for extracting valuable metals, disposing e-waste, and dealing with byproducts of the recycling process such as acid. The UNEP has further worked with NGOs such as the Stop The E-waste Problem (StEP) to publish “Recycling-From Ewaste to Resources” that informs e-waste producing companies and businesses to properly dispose of their products. The UNEP works to improve communication between and within nations to make combating e-waste a collaborative effort. source: Howard. Current Status In the United States, in December of last year, Executive Recycling was found guilty in federal court of exporting hazardous material to developing nations ("Electronics Recycler UCMUN 2013 United Nations Environmental Programme Topic A: E-Waste Convicted for Illegal Exports to Developing Countries"). This event brought the issue of e-waste to the news. Because of this increased media coverage this year, federal legislation called the Responsible Electronics Recycling Act (RERA) was introduced in Congress. The bill would ban exports of “untested and non-working e-waste”, but would allow “free trade of tested and working used electronics being exported for reuse” ("Electronics Recycler Convicted for Illegal Exports to Developing Countries"). This legislation is mainly aimed at keeping the recycling and reusing process within national borders, and preventing developing nations illegal access of hazardous waste. It still remains to be seen how this process will be made more efficient and safe within borders. In the EU, the 2003 Waste Electrical and Electronic Equipment (WEEE) directive is being updated to “significantly strengthen a range of e-waste regulations and impose new targets” (Murray). Their current policy will emphasize reuse and recycle policy in addition to many other areas of the issue. Internationally, the EPA and UNU-StEP have been hosting workshops and meetings for policymakers and enterprises of several nations to discuss their efforts and collaborate on ways to address the current situation. In March of 2012, for example, there was a UNEP-hosted Pan African Forum on E-waste in Nairobi. “Over 180 participants shared experiences and research from Africa and efforts from other continents that could be demonstrated in Africa. A set of priorities to support a regional approach was developed in the form of a Call for Action” ("Cleaning Up Electronic Waste (E-Waste)"). The UNU-StEP further worked with Ethiopia specifically to help the government create a national e-waste management policy ("Cleaning Up Electronic Waste (EWaste)"). E-waste is a fairly new sector and efforts surrounding it have been initiated recently. Policies being implemented today are yet to be observed to see how effective they are. UCMUN 2013 United Nations Environmental Programme Topic A: E-Waste Bloc Positions The main division in nations lies between importing and exporting nations. Developing and industrializing nations, in particular China and India, are the main importers of e-waste. Other nations that also import e-waste are South Africa, Uganda, Senegal, Kenya, Morocco, Brazil, Columbia, Mexico and Peru. These nations may choose to focus on how importation can be regulated, recycling can make an organized effort, health and environmental effects can be combated, and human rights can be maintained. They may choose to collaborate with exporting nations to achieve these goals. North American and EU nations have policies on waste exportation and recycling. However, these are not necessarily strictly enforced. In our committee, these nations may specifically choose to target how they can reduce e-waste production, inform the population of proper disposal, and research and implement proper disposal and recycling policy within borders. They may look to current policy and improve upon what already exists. The line between e-waste producer and importer does not necessarily correspond to developed and developing nations respectively. China and India, for example, are also among the biggest global producers of e-waste. These nations may create goals that coincide with both e-waste importing and producing countries. UCMUN 2013 United Nations Environmental Programme Topic A: E-Waste Committee Mission E-waste is a complex and widespread issue. However, there is not a lot of history to reflect on and learn from since it is also a new issue. In order to tackle the matter, international cooperation is integral. Specifically, regulation is key. In developing nations this is regarding importation of banned e-waste, proper recycling methods, human rights and safety of workers. In more developed nations, this may entail disposal within borders and exportation. In both cases, everyday citizens as well as relevant corporations must be informed about their role in the issue and how they can help. The UNEP exists to help nations create their own policies regarding e-waste and most importantly, enforce these policies. Questions to Consider 1) How can individual nations take control of what happens within their borders? Pay attention to governments turning cheek on illegal practices, governments with no national policy, and the education of workers. 2) How can the international community play a role in regulating where e-waste goes, and who handles e-waste? 3) What has your country in specific acted on the issue of e-waste? How successful/un successful have they been? 4) What motivates your country to act the way it does with regards to e-waste? 5) Can e-waste management be compared to other ecological issues with a more clear history? Can we look to the Kyoto Protocol, for example, for ideas? 6) What can the UNEP do to help your country and others? UCMUN 2013 United Nations Environmental Programme Topic A: E-Waste Works Cited "The Bane of Hi-tech Waste." Web log post. The PCIJ Blog. Philippine Center for Investigative Journalism, 10 Oct. 2008. Web. 16 May 2013. The official blog of the Philippine Center for Investigative Journalism summarizes some of the health hazards and the transportation of e-waste. It references legitimate sources for its facts. Although a blog is generally not a reliable source, blogs from news networks or other reliable sources are helpful and good to use. "A Cadmium Lining." The Economist 26 Jan. 2013: n. pag. Print. This article published in the Economist magazine is a reliable source. Since e-waste is a very new topic, finding journal articles will be harder to find. However, to keep up with current news, newspapers and magazines are great sources. This article in particular summarizes some of the effects of e-waste in developing countries. It even provides some pictures of ewaste recyclers in developing countries. "Cleaning Up Electronic Waste (E-Waste)." EPA. Environmental Protection Agency, n.d. Web. 16 May 2013. This webpage from the US EPA provides recent and upcoming events that international agencies and the UN are involved in concerning e-waste. "Electronics Recycler Convicted for Illegal Exports to Developing Countries." Basel Action Network. Basel Action Network, 22 Dec. 2010. Web. 16 May 2013. The Basel Action Network provides some of the latest news regarding e-waste and other hazardous waste trade. The website can further be used to learn more about the Basel Convention, the nations that have ratified it, and how it is being implemented into policy. E-WASTE: The Exploding Global Electronic Waste Crisis. Publication. Electronics Take Back Coalition, Feb. 2009. Web. 16 May 2013. This is a short eBook that summarizes the e-waste problem, gives information on the specific toxins that affect health of recycle workers, gives statistics, and proposes some possible solutions to the e-waste issue. Howard, Brian C. "Visualizing the Growing E-Waste Epidemic." News Watch. National Geographic, 14 Mar. 2012. Web. 16 May 2013. This post from the National Geographic has some great visual depictions of e-waste statistics and facts. "International Legislation & Policy." Sustainable Electronics Initiative. University of Illinois, n.d. Web. 16 May 2013. This website is run by a university and is a reliable source. It summarizes some of the legislation that have been passed and are being worked on in different regions of the world. UCMUN 2013 United Nations Environmental Programme Topic A: E-Waste This is a great start to understanding a delegate’s own policy and a good guide to further research. Jugal, Kishore, and Monika Jugal. "E-Waste Management: As a Challenge to Public Health in India." Indian Journal of Community Medicine 35.3 (2010): 382. NCBI. Web. 16 May 2013. <http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC2963874/>. This journal article summarizes the state of e-waste in India with information on the practices and health of recyclers, and current and future policy. Luther, Linda. Managing Electronic Waste: Issues with Exporting E-Waste. Publication. Congressional Research Service, 27 Sept. 2010. Web. 16 May 2013. This publication summarizes impacts of e-waste, how it is exported from the United States, what the current requirements for disposal are in the US, and some of the problems there are with the current system. Murray, James. "EU Revamps E-waste Rules with Demanding New Recovery Targets." The Guardian. Guardian News and Media, 14 Aug. 2012. Web. 16 May 2013. This news article summarizes some of the changes that EU nations are hoping to bring in the coming years regarding e-waste. Olowu, Dejo. "MENACE OF E-WASTES IN DEVELOPING COUNTRIES: AN AGENDA FOR LEGAL AND POLICY RESPONSES." Law Environment and Development Journal 8.1 (2012): 59-75. Lead-Journal. University of London and the International Environmental Law Research Centre, 2012. Web. 16 May 2013. This article from an environmental law journal gives information on transport of e-waste, relevant policy and law, human rights, and some strategies to combat the issue. Schluep, Mathias, Christian Hagelueken, Ruediger Kuehr, Federico Magalini, Claudia Maurer, Christina Meskers, Esther Mueller, and Feng Wang. Recycling - From E-Waste to Resources. Publication. UNEP StEP, July 2009. Web. 16 May 2013. This is a study conducted by the UNEP that focuses on recycling of e-waste metals. It proposes new technologies for this recycling process and explores application and possible integration of these technologies. Walsh, Bryan. "E-Waste Not." Time. Time, 8 Jan. 2009. Web. 16 May 2013. Another magazine article summarizes the e-waste problem and some of the news and facts during the time it was published. "Where Does E-waste End Up?" Greenpeace International. Greenpeace International, 24 Feb. 2009. Web. 16 May 2013. This webpage summarizes the different ways e-waste is disposed of, including dumping in landfills, destroyed in incinerators, and exported to other nations. UCMUN 2013 United Nations Environmental Programme Topic A: E-Waste Wirfs-Brock, Jordan. "E-Waste Laws State by State." E-Waste Laws State by State. I-News Network, n.d. Web. 16 May 2013. The I-News-Network published an image depicting which US states have e-waste laws and which do not. UCMUN 2013 United Nations Environmental Programme UNEP Topic B First Draft: Reducing Anthropogenic Mercury Emissions Introduction Mercury is a naturally occurring metal that can pose great risks to human health and the environment. It can be released from the earth through natural and human causes. Some of these human causes include steel production, coal burning, and gold mining. After release, mercury can enter the atmosphere and the food chain and can go on to cause serious health and environmental effects. In recent years, negotiations have taken place to reduce emissions globally. The UNEP will look at how mercury emissions affect humans and the environment internationally and how we can work to combat the negative effects. Figure 1 Estimated proportion of global anthropogenic mercury emissions in 2010 from different sources (The Global Atmospheric Mercury Assessment) Topic History Mercury occurs in the earth’s crust, and is released by natural causes such as volcanic eruptions and erosion. A lot of mercury, however, is also released due to human activity. When coal, a major global energy source, is burned, mercury deposited in the rocks is released. Further sources are “burning hazardous wastes, producing chlorine, breaking mercury products, spilling mercury, improper treatment, disposal of products or wastes containing mercury”, and separating metal from ore in small-scale gold mining (“Basic Information”). Mercury is useful as UCMUN 2013 United Nations Environmental Programme UNEP Topic B First Draft: Reducing Anthropogenic Mercury Emissions a chemical and pharmaceutical agent as well, and small amounts are manufactured in some nations for these purposes, but largely, mercury release is an unwanted byproduct of other processes. Figure 2 Anthropogenic mercury emissions from different regions from 19902005 (“Basic Information”). These processes can release mercury into the environment in a number of forms: elemental, bound within particles, or oxidized. The type of mercury can affect how far the element can travel once released in the air and the effects posed on human health and the environment (“Basic Information”). Methyl mercury, a compound, is the most dangerous of these forms to humans and most commonly enters a person’s system through consumption of fish (“Mercury Impacts to the Environment”). Once mercury is emitted into the atmosphere, it precipitates and accumulates into land and water. This is converted to methyl mercury by bacteria found in soil and sediments, and eaten by small organisms. Subsequently, biomagnification transports mercury up the food Figure 3 The Mercury Cycle (“Mercury Impacts to the Environment”). chain, affecting other wildlife and human consumers (“Mercury Impacts to the Environment”). Fish, bird, and small mammals are greatly affected by mercury in the environment: studies have shown UCMUN 2013 United Nations Environmental Programme UNEP Topic B First Draft: Reducing Anthropogenic Mercury Emissions subtle visual, cognitive, and neurobehavioral deficits in affected animals. In humans, mercury consumption in high levels can affect the heart, kidneys, lungs, the immune system, and mostly the brain and nervous system. Pregnant women, unborn babies, and young children are more susceptible to the health effects of mercury exposure. In the past, there have been outbreaks of mercury poisoning. Often called Minamata disease, mercury poisoning was first seen large scale in the Japanese city of Minamata in 1956. A chemical factory discharged large amounts mercury byproduct into the Minamata Bay which bioaccumulated in fish and shellfish. Seafood consumption in the area caused serious illness and death (Harada 2). Case Study: Small Scale Gold Mining in Colombia Mercury can also harm people through direct exposure to the processes that utilize the element. Almost 70 nations are involved in gold mining, especially small scale, one of the largest contributors to atmospheric mercury (Barber). Small-scale gold mining releases approximately 400 metric tons of airborne elemental mercury each year (Bailey). In these gold shops, or small-scale gold mining sites, mercury is burned in order to separate gold from ore and sediments. The process releases highly toxic mercury vapors that result in atmospheric mercury levels that exceed limits set by the World Health Organization. These gold shops are mostly unregulated in developing nations such as Colombia. Mercury and other products are obtained illegally and used in unregulated methods. Workers are not paid well and have little information on the devastating effects on their health. Oftentimes, livelihoods of these workers and their families depend on their work. With an increase in gold prices worldwide since 2002, the demand for small-scale gold mining continues to increase, and with it, mercury pollution and the environmental and human rights problems that arise with it. Gold mining in Colombia has been the fastest growing industry in the past decades. 200,000 small-scale miners producing more than 50 percent of the country’s gold. As a result, Colombia is UCMUN 2013 United Nations Environmental Programme UNEP Topic B First Draft: Reducing Anthropogenic Mercury Emissions also one of the world’s leading mercury emitters (Siegal). In developing nations such as Colombia, poverty, global economy, environment and health are all interrelated in this complex dilemma of mercury use in gold mining (Nuttal & Bryan). UCMUN 2013 United Nations Environmental Programme UNEP Topic B First Draft: Reducing Anthropogenic Mercury Emissions Current Status International negotiations have been ongoing in the past years and in January 2013, more than 140 nations collaborated on a legally binding treaty at the Minamata Convention that will aim to reduce these emissions. The Convention will require nations to work to reduce the mercury levels in the air and used in industrial processes, especially small scale gold mining. They will further have “to address mercury supply and trade,” This is still the first step towards combating the problem of mercury emissions; nations must still work out the specifics of the treaty and apply it to their own governments. In October 2013, the Minamata Convention will be open for signatures. In addition, the UNEP Mercury Products Partnership has set standards to reduce mercury in common devices such as thermometers, USA’s Mercury and Air Toxics Standard will reduce UCMUN 2013 United Nations Environmental Programme UNEP Topic B First Draft: Reducing Anthropogenic Mercury Emissions mercury emissions in the coming years, the EU and US placed bans on mercury exports in 2011 and 2013 respectively, and national action plans were made by Argentina, Uruguay and other countries in coordination with the UNEP. These are all examples of preexisting ways the global community has taken action to reduce emissions (“The Global Atmospheric Mercury Assessment”). However, action has still been slow and the 2013 Minamata Convention is the first step to changing that in a wellcoordinated and organized manner. Furthermore, although some restrictions exist, the key lies in enforcement, as well as innovation that will allow for economically integral sectors, such as artisanal gold mining, to thrive but through environmentally sound ways. Bloc Positions Emissions due to gold mining and electricity generation (through coal burning) are largely seen in developing nations in Africa, South America and mostly Asia (Nuttal & Bryan). Asia now contributes to just under half of global emissions. Much of this mercury ends up in fresh water lakes and rivers and contaminates wildlife such as fish, which in turn affect the human consumers of fish. This bloc of nations may focus on how to reduce these particular sources of emissions internally and may collaborate with each other on how to do so. Delegates may further divide within this bloc according to what the major source of their respective nations’ mercury emissions are. This may coincide with geographic differences. For examples, deforestation has been proven to release mercury into the atmosphere, especially in the Amazon (Veiga, Meech & Ornate). Nations in which deforestation is a problem (those in South America) may choose to work together to address the problem. In this bloc, mercury is a byproduct of industrial processes that are important to the economy. Thus, it may be difficult striking a balance between allowing freedom for economic stimulation and enforcing laws that will help protect the population and environment. Regulation and formalization of the different sectors (such as gold mining, metal production, etc.) is key. UCMUN 2013 United Nations Environmental Programme UNEP Topic B First Draft: Reducing Anthropogenic Mercury Emissions Furthermore, collaboration with more developed nations may consist of combating the need for exportation of mercury from these nations. More developed nations form another bloc. These nations may address how to reduce use of mercury and mercury products, and cut emissions from more relevant sources such as fossil fuel combustion, steel production, and large-scale mining. The same idea goes for further divisions: nations that have similar mercury emission trends should collaborate with each other to reduce emissions and develop more sustainable practices. Committee Mission Mercury emissions are a growing problem that has reached international attention. Although there are natural causes, the goal of the UNEP is to minimize emissions that are a result of human action as well as pave the way for more sustainable technology and practices that will eliminate those that destruct the environment. Major sources of emissions differ from geographic region-to-region and even with regions. Thus, it will be important to look specifically at leading sources of mercury emission in different regions and address those specifically, taking into account the economic and environmental consequences that these sources have. Questions to Consider: 1) What are the major contributors to mercury emissions in your nation and region? 2) What are the economic and political implications of noticeable trends in mercury emissions? 3) What has your nation already done to combat the problem? What have other nations done that you can learn from? 4) How can regulation, legislation, and innovation help create more sustainable practices in your nation? UCMUN 2013 United Nations Environmental Programme UNEP Topic B First Draft: Reducing Anthropogenic Mercury Emissions 5) How can you collaborate with other nations in the UNEP to both help your nation and others worldwide? UCMUN 2013 United Nations Environmental Programme UNEP Topic B First Draft: Reducing Anthropogenic Mercury Emissions Works Cited Bailey, Marianne. "Reducing Mercury Pollution from Artisanal and Small-Scale Gold Mining." EPA. Environmental Protection Agency, 18 July 2013. The EPA is a federal group that writes and enforces environmental regulations in the US. Their website provides information on the mercury emissions problem both within the US and outside. It also gives information on the latest events that have happened regarding this topic. Barber, Ben. "140 Countries Vow to Cut Toxic Mercury Release." The Huffington Post. TheHuffingtonPost.com, 20 Feb. 2013. This is an article on the recent Minamata Convention. Credible articles like this can be used to find information on big events or news. "Basic Information." EPA. Environmental Protection Agency, 9 July 2013. Web. 8 Aug. 2013. This is another page of the EPA website. Multiple pages provide a wide variety of information on mercury. The Global Atmospheric Mercury Assessment: Sources, Emissions, and Transport. Publication. UNEP Chemicals Branch, Dec. 2008. Web. 8 Aug. 2013. This report from the UNEP analyses major sources of mercury emissions, trends in emissions, and how these emissions are transported and deposited in the earth. This is a UCMUN 2013 United Nations Environmental Programme UNEP Topic B First Draft: Reducing Anthropogenic Mercury Emissions good source for information on trends of mercury emissions since the reader can compare newer findings with this from 2008. Harada, Masazumi. "Minamata Disease: Methylmercury Poisoning in Japan Caused by Environmental Pollution." Crit Rev Toxicol 25.1 (1995): 1-24. PubMed. Web. This journal article looks into the specific symptoms and cases of Minamata disease and analyzes `them in a medical context, as well as giving much historical evidence. "Mercury Impacts to the Environment." Mercury Impacts to the Environment. United States Department of Agriculture, 20 Feb. 2013. Web. 8 Aug. 2013. This page from the USDA website gives information on how mercury emissions impact the environment, affecting wildlife and even climate change. Nuttall, Nick, and Bryan Coll. "UNEP Studies Show Rising Mercury Emissions in Developing Countries." United Nations Environment Programme. United Nations Environment Programme, 10 Jan. 2013. Web. This articles gives information on international negotiations that have taken place in the past and are expected in the future regarding mercury emissions. It gives some basic information on mercury emission trends, impacts and actions taken internationally. Siegel, Shefa. "Threat of Mercury Poisoning Rises With Gold Mining Boom." Yale Environment 360. Yale School of Forestry & Environmental Studies, 3 Jan. 2011. This report gives information on gold mining centers in Colombia, in specific, Segovia. It tells the story of a worker who fell seriously ill, gives information on the bad conditions of UCMUN 2013 United Nations Environmental Programme UNEP Topic B First Draft: Reducing Anthropogenic Mercury Emissions workers, the poverty that surrounds the sector's workers, and the economic implications of gold mining in Colombia and other parts of the world. Global Mercury Assessment 2013. United Nations Environment Programme. United Nations Environment Programme, Jan. 2013. Web. This is the latest report on mercury emissions published by the UNEP this year. It gives full overview of major sources, impacts on health, environment and economy, pathways in terrestrial and aquatic environments, trends in emissions and more. This is a very good source for visual depictions of information that help put things into perspective. Veiga, Marcello M., Meech, John A. and Onate, Nilda. "Mercury Pollution from Deforestation." Diss. University of British Columbia, n.d. Mining.UBC. University of British Columbia. Web. Traditionally, mercury released from cutting down trees has not been analyzed in reports of mercury emissions. This source argues that deforestation is a major source of mercury release and is affecting the health of deforestation workers.