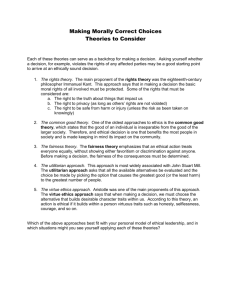

Ethics Workbook - Teacher Support

advertisement

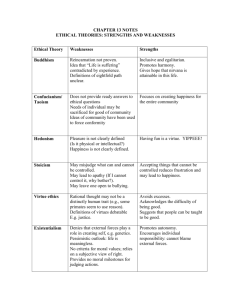

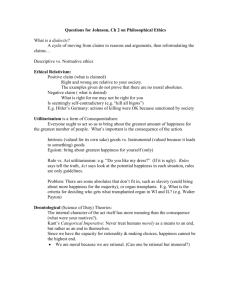

Ethics Workbook Bite Size Basics of Ethical Theory 1 Introduction This workbook is an introduction to some key ideas underpinning some ethical theories. As a student of Global Perspectives you are not required to know these theories but you may find them useful when considering why something may be considered good or bad/right or wrong. In Global Perspectives, it is important that you think about the criteria you use to make judgements and consider that other people may have differing criteria. The theories introduced here are primarily from a Western perspective – so you should consider researching ethical and religious principles and theories from Eastern perspectives too (e.g. Confucianism, Buddhism, Hinduism, Taoism, and Islam). 2 Categorising Ethical Theories Ethical Theory is divided into three general areas and a fourth slightly different category: Descriptive Ethics describes and compares the different ways people and societies answer moral questions. An example would be ‘What do Christian and Muslim traditions believe about sex before marriage?’ A description would normally follow in answer. Normative ethics involves processes and systems we use to arrive at the ethical decisions we make. Meta-ethics investigates the source, meaning and function of ethical language e.g. what do we mean by the words good, love etc. Applied ethics applying ethical systems in order to resolve controversies e.g. abortion, homosexuality etc. Meta-ethics Meta-ethics explores the meaning and function of moral language. What, if anything, do we mean when we use the word ‘good’ or ‘bad’ or ‘right’ or ‘wrong’. Theories that fall into metaethics are ‘naturalism’, ‘intuitionism’ and ‘emotivism’, objectivism and subjectivism. Normative ethics Normative ethics involves arriving at the ethical standards that regulate behaviour. The key assumption is that there is only one ultimate principle of ethical conduct whether it is a single rule or set of principles. It is common to classify ethical theories into several categories: 1. Consequentialist or teleological theories 2. Deontological theories 3. Virtue theories Consequentialist theories Consequentialist (teleological) theories determine ethical behaviour by weighing up the consequences of an action. The consequences of an action are looked at within a given framework of thinking or set of criteria. If the perceived outcome or consequence of the decision is likely to match the framework or set of criteria, then the action is ethically proper. Deontological theories Deontological ethics is concerned with the nature of the acts themselves. Deontologists maintain that acts are right or wrong in themselves because of some absolute law perhaps laid down by God (e.g. Natural Moral Law), or because of some duty or obligation (Kant formulated the notion of a categorical imperative which requires that actions toward another person should reflect obligation and duty). A deontologist might say that murder is wrong because the very act of murder is wrong. Virtue theory Virtue theory suggests that ethical behaviour is the result of virtues or good habits of character. Commonly suggested virtues include: wisdom, courage, temperance, justice, 3 fortitude, generosity, self-respect, good temper, and sincerity. Vices or negative virtues include cowardice, insensibility, injustice, and vanity. 4 Normative Ethics: Consequentialist Theories Utilitarianism 1 Jeremy Bentham (the man who left his body to University of London in a glass fronted wardrobe!) Principle of Utility – The greatest good for the greatest number. We should always aim to maximise pleasure and minimize pain. Therefore, in a given situation, one must examine the consequential pain/pleasure for all concerned. Hedonic Calculus – Bentham devised the Hedonic Calculus which was designed to help us weigh up the pain and pleasure generated by the available moral actions to find the best option. It considers several factors: a. Intensity b. Duration c. Certainty or uncertainty d. Nearness or remoteness e. Consequences f. Purity g. Extent If the probable pain of an action outweighs its pleasure then Bentham says that it is morally wrong. Problems If 10 robbers were to steal from the same woman, then using the Hedonic Calculus, their pleasure would outweigh the woman’s pain. Therefore, it would become justifiable. This is called the Swine Ethic. Consequences are not always measurable because we do not know how far the effects of our decisions will reach. There is no protection for minority groups. Sometimes we need to suffer for the greater long term good - ‘no pain, no gain’. Utilitarianism 2 John Stuart Mill criticised Bentham for focussing morality on pleasure alone, which seemed rather base to him. So, he decided to introduce a theory of utility for the common person , which replaced pleasure for ‘happiness’ (“the greatest happiness for the greatest number”) and moved away from mere quantity to the quality of happiness as well. Mill defined happiness as something which is cultural and spiritual rather than just physical and distinguished between lower pleasures and higher pleasures. In other words, it is far more pleasurable to have a philosophical discussion than a bar of chocolate. He famously wrote: 5 “It is better to be a human being dissatisfied than a pig satisfied, better to be Socrates dissatisfied than a fool satisfied.” Problems Sidgewick – “In practice it is hard to distinguish between higher and lower pleasures.” This is due to the subjectivity of “pleasure”. WD Ross – “Single-factor” moral theories don’t work because life is too complex. We have “prima facie” duties i.e. who would I save – my son or a man with the cure to AIDS? – My son because my prima facie duty is to him. RM Hare – you would still have to tell the truth to a mad axe man. It would still be possible to justify slavery – minority rights not protected. Comparing Bentham and Mill Bentham Mill “the greatest good [pleasure] for the greatest “the greatest happiness for the greatest number” number” Focussed on the individual alone We should protect the common good Atheistic Hedonic Calculus (quantitative pleasure) Higher/lower pleasures (qualitative) General good bits of Utilitarianism Supports the notion that human wellbeing is generally good. Supports Jesus’ call to treat others as you would have them treat you. Consequences affect life, not motives. Encourages democracy. General problems of Utilitarianism Difficult to predict consequences. The theory disregards motivation and goodwill. Says that the majority is always right (e.g. Nazis in World War II). Does not protect the minorities. The single criterion for morality is far too simplistic. Morality cannot rely on pleasure and happiness alone – life is too complex. 6 Situation Ethics Joseph Fletcher wrote from a Christian perspective, but thought that morality was not simply about following set rules indefinitely (e.g. 10 commandments), but was also about autonomy (taking responsibility for one’s own actions). He strongly rejected legalism (following concrete laws), but also rejected its opposite, antinomianism (where there is no morality at all and no basis on which to judge actions). He attempted to find the middle ground. Instead, he said that Christians should base morality on one singe rule: the rule of agape i.e. given any moral dilemma, one must ask themselves: what is the most loving thing to do in this situation? Not content to leave it there, Fletcher proposed the 6 fundamental principles of Situation ethics: 1. 2. 3. 4. 5. 6. Agape love is the only absolute good. Everything else is relatively good. Agape love is the principle taught by Jesus. Justice will automatically follow from love, assuming that everyone follows the principle. Love has no favourites, everyone is equally valuable. Love must be a final end that people seek. It must not be a means to an end. The loving thing to do depends on the situation – thus it is regarded as a relativistic approach to morality. Good Bits of Situation Ethics People are able to take responsibility for their own moral decision making. Situation ethics provides a way for people to make decisions about issues not addressed in the Bible. I.e. birth control, genetic engineering etc. Situation ethics is based on the teachings of Jesus and so can be considered a Christian ethic. Problems with Situation Ethics Pope Pius XII argued that Situation ethics was wrong to appeal to individual circumstances in an attempt to justify what clearly went against the teachings of the church. Situation ethics asserted that the individual was more important than the teachings of church and of the Bible. The approach can be said to expect people to have greater insight than most of us possess. How can you know what is the most loving thing to do? Also, no one can truly be objective in decision making. Situation ethics gives people too much responsibility. Most people want to be told what is right absolutely rather than deriving a conclusion themselves because they cannot always see what the best solution is. If two people using the approach arrived at different conclusions, it is impossible to judge which one is right, since there is no absolute. Humans tend to be selfish. 7 Normative Ethics: Deontological Theories The Divine Command Theory of Ethics What makes an action right is what God wills to be done – whatever God says goes! Examples would be the 10 Commandments, Biblical passages pointing out God’s will e.g. the story of God telling Abraham to sacrifice Isaac etc. Weakest Version: God’s commands are applicable within the context of specific religious communities (i.e. Fundamentalist Christians would say homosexuality is wrong). Stronger Version: Moral behaviour is good in and of itself and that we should do this because God wills it (i.e. God wills the good because it is good). Strongest Version: Moral behaviour is good because it is willed by God. Good Bits of Divine Command Theory At least you know where you are up to with a set of God’s rules – there’s no wiggle room or doubt! Problems with Divine Command Theory The Euthyphro Dilemma - 'Is the holy approved by the gods because it's holy, or is it holy because it's approved?' In other words, is something good because God said it is (how do we know God is always right?) or does God choose that which is right and then pass the decision on to us? The latter would suggest that goodness precedes God! The main problem is that whatever God says goes. This means the Ten Commandments could have instead been, ‘You shall kill people you do not like’, You shall steal’ etc... Although a theist, Leibniz argued that to believe God could do this was to destroy whatever grounds one had for praising and worshipping God. Natural Moral Law Thomas Aquinas (13c Christian Theologian and Doctor of the Church) took Aristotle’s teachings and expanded on them. He nearly got into extremely big trouble for this because Aristotle was a pagan! Aquinas’ thought that there are absolute laws, which govern the way the world works for example the law of gravity. In the same way, Aquinas postulated that right and wrong, good and evil follow a natural law and that we can discover this through our reason and observation. God created the world He gave it a sense of order He created everything for a purpose We must use our reasoning to work out what that purpose is 8 We must act in order to conform to that purpose Acting towards that purpose brings us closer to God’s will. Good bits of Natural Moral Law The usual strengths of a deontological/absolute system i.e. it provides clear and fixed rules that always apply, removing confusion and exception. Objective laws means they apply to everyone. Common human nature allows us to establish ideas like universal human rights. Avoids the relativist fallacy (which stated that truth is relative, not absolute; when by its nature according to Aquinas, truth is absolute). Has an empirical basis (in the actual nature of things) and can therefore be verified. Does not rely on a consideration of consequences, like utilitarianism and situation ethics and therefore avoids calculations and quantities of good/happiness. Problems with Natural Moral Law Can be said to be counter-intuitive (goes against common sense) e.g. it seems to make sense to endorse contraception in over-populated countries, but NML demands adherence to objective laws. It suggests every human adult should marry and have children – does this mean Mother Teresa was wrong to devote her life to helping the poor instead? Or that Thomas Aquinas was wrong to have been a priest? The idea that there is a common human nature may be challenged (e.g. homosexuality/disability). Aquinas tackled this challenge by maintaining it is acceptable for some people to choose other ways of life. However, this seemingly allows some people to consider themselves exempt from the rules whilst imposing the same rules on others. The possibility of the existence of objective laws has been challenged by many. Aquinas’ underlying assumptions (God’s existence/soul etc.) may be challenged, negating the whole theory. Kant’s Deontological Ethics – The Categorical Imperative Immanuel Kant presented his thinking thus: 1) 2) 3) 4) 5) 6) 7) 8) 9) The universe is fair All human beings desire and seek happiness All human beings ought to be moral and do their duty The Summum Bonum (the highest good) represents the combination of virtue and happiness Everyone seeks the summum bonum What is sought must be achievable because the universe is fair! The Summum Bonum is not achievable in this life (obviously – there is no totally good person on the planet). So it is necessary to POSTULATE (suggest/imply) a life after death in which the Summum Bonum can be achieved AND it is necessary to POSTULATE a God to guarantee fairness. 9 ‘Two things fill the mind with ever new and increasing admiration and awe, the more often and the more steadily they are we reflect upon: the starry heavens above me and the moral law within me.’ Kant Kant maintained that it is our duty to act morally correctly irrespective of the outcome of our actions. To help us to work out what constitutes our duty, Kant proposed the Principle of Universalisation: In order to check and make sure we are doing our duty, Kant suggested we universalise the rule we are thinking of applying. For example ‘you are allowed to steal’ – if this is applied to everybody in the world and then the world continues peacefully, this would become your duty. However, we know that if you do allow people to steal, chaos would ensue. Therefore the rule cannot work and must not be applied. Good Bits of the Categorical Imperative The categorical imperative does prohibit acts that are commonly seen as immoral such as theft, murder and sexual abuse. It does not rely on predicting outcomes or happiness and it is rational and certain. Kant gives Humans intrinsic worth (ends in themselves) promoting equality. Problems with the Categorical Imperative Kant refuses to allow exceptions to a maxim, which is not continuous with modern politics. In war, the sacrifice of the few for the many is sometimes necessary. A morality in which results are left out of account seems detached from reality and impractical. It is very hard to separate reason from emotions such as compassion. Some might argue that emotions play an important part in ethical decision making. The categorical imperative could be applied from a selfish point of view; for example I could say that it is wrong to steal on the grounds that if everyone stole I would have little hope in retaining what I had just stolen. This self-centred view of morality is counter-intuitive. 10 Normative Ethics: Virtue Ethics Aristotle The ancient Greeks recognised virtue as a central element of ethical thinking. Virtue is particularly important in the writings of one such ancient Greek - Aristotle. The difference with Virtue Ethics is that it looks at the person we need to be in order to make the correct moral judgements i.e. we should aim to become a virtuous person with the implication that a virtuous person will always make the correct decisions. Aristotle’s thinking: We are judged by our character, not specific actions. An individual who has developed good character traits (virtues) is judged as a morally good person. An individual who has developed bad character traits (vices) is judged as a morally bad person. Most of us have a mixture or virtues and vices. Aristotle believed that the moral man was the man of virtue. He did not see virtue as the opposite of vice. Virtue is the mean between two extremes – a middle way. For example, courage is the mean between cowardice and foolish bravado. Finding this middle way is the key to leading a moral life. Virtues included: Courage, Friendship, Justice, Temperance (self-control) and Wisdom. Good Bits of Aristotle’s Virtue Ethics It involves all aspects of human life. It’s compatible with Christian ethics. Forces us to concentrate on what is means to be a good person. Problems with Aristotle’s Virtue Ethics Virtue theory still depends on moral absolutes and is no more than a “disposition to obey moral rules” (Schaller 1990). Does not give answers to specific moral dilemmas e.g. abortion. Frankena says that using history to inform morality is wrong. Scheffler says the exercise of good virtue does not always lead to happiness. The theory creates an over criticism of the modern world. Aristotle’s given moral and intellectual virtues are culture bound. He is racist, sexist and ageist by today’s standards. 11 Aquinas and Virtue Thomas Aquinas states that perfect happiness (beatitudo) is not possible on earth, but an imperfect happiness (felicitas) is. This puts Aquinas midway between those like Aristotle, who believed complete happiness was possible in this lifetime, and another Christian thinker, St. Augustine, who taught that happiness was impossible and that our main pleasure consists merely in the anticipation of the heavenly afterlife. Aquinas held the following views about human happiness and virtue: Perfect happiness (beatitudo) is not possible in this lifetime, but only in the afterlife for those who achieve a direct perception of God. There can be an imperfect happiness (felicitas) attainable in this lifetime, in proportion to the exercise of Reason (contemplation of truth) and the exercise of virtue. Virtue is to be divided into two categories: 1) the traditional Aristotelian virtues of wisdom, courage, moderation, friendship, etc., and 2) the theological virtues revealed to man through Jesus Christ: faith, hope, and love. There is an important distinction between enjoyment and happiness. Enjoyment concerns satisfaction of worldly desire. Happiness concerns obtaining our absolute perfection, which by definition can only be found in the absolute Being, which is God. Ross on Prima Facie Duties ‘Prima Facie’ means loosely “at first glance”. Ross maintains that there are a variety of duties, and provides a short list that is not intended to be an exhaustive list, but that covers some of the duties that we have. Those duties are broken up into two categories: duties we owe to others, and duties we owe to ourselves. Duties we owe ourselves: These are the duties of Prudence: – Self-improvement, physically, mentally, morally, etc. – Note that these aren’t duties to do whatever you want, they are duties to do what is best for you. Duties we owe to others: Fidelity (keeping promises we have made, maintaining personal relationships we have entered into) Reparation (compensating people for wrongs we have done them) Gratitude (doing good to those who have done good to us) Beneficence (helping others in need when we can) Non-malevolence (doing no harm) Justice (giving everyone what they deserve, and not withholding what people deserve) When duties conflict, we must determine which duty is more important. There is not a fixed hierarchy of duties. For example, our duty of benevolence in saving a child from drowning would outweigh our duty to meet a friend for lunch if we happened to see a child drowning on the way to lunch. However, a promise to buy one’s child shoes for dance class would outweigh a duty of benevolence in giving some money to a penniless traveller. 12 Problems with Ross’ Virtue Ethics Nice thinking at first sight but… Ross’s system pays for its plausibility with its complexity and uncertainty. 13 Meta Ethics Emotivism The roots of Emotivism are found in Logical Positivism: There is no point discussing anything that cannot be empirically verified. Key thinkers: A. J. Ayer 'Language, Truth and Logic' (1936) C. L. Stephenson 'Ethics and Language' (1947) Key ideas (Ayer) Ethical statements are not facts in that they are either true or false (e.g. Synthetic statements). ‘…ethical concepts are un-analysable, insomuch as there is no criterion by which one can test the validity of the judgments in which they occur… Another [person] may disagree with me.’ Ayer is not concerned with what ethical statements mean but what they are for. Ethical statements are simply personal preferences akin to saying 'I like this but not that' (an emotional response): Murder is wrong! "I do not like murder" "Murder... Boo!" The appeal to base ethics on something else is a further appeal to emotions: I base my ethics on Jesus' teachings I like Jesus' teachings Jesus... Hooray! Developments (C. L. Stephenson) Agreed with Ayer that ethical statements are an appeal to emotions yet added that there was also an element which sought to persuade. He also believed that people could disagree in their methods towards achieving the same end (e.g. curing a patient). This means ethics is more than an 'emotional shouting match'. Moral disputes are disagreements about fundamental principles. 14 Problems Emotivism has no basis on which to ground, and justify, it's judgments. On what basis should anyone's actions be considered wrong (or right)? Behaviour considered immoral could be justified on the basis that one might 'like it' (e.g. Murder... hooray!) Emotivism simply reports ethical behaviour. However... Emotivism forces ethical philosophers to take seriously the treatment of ethical language: "Do not do that!" - Is this true or false? Ethical statements DO express personal opinions but is that all they are? Naturalism Ethical values can be ‘scientifically’ tested and evaluated. This would be done on the basis of observation (or ‘sense-perception’). Moral ‘facts’ are not personal opinions. When one ‘sees’ something that is wrong it is wrong. For example, if I see a murder occurring I do not just see just the act itself but I also see that the act is wrong (i.e. the effects it produces). When people observe that something is wrong it is a moral ‘fact’ of the universe. Intuitionism G. E. Moore in Principia Ethica rejected what he called the ‘Naturalistic Fallacy’. He believed the idea of ‘good’ was a simple one that could not be based on anything else. Something is good or bad in itself rather than because of the effects it produces. Moore essentially argues that there can be no ‘ought’ from ‘is’ (‘ought’ (moral conclusion) cannot be derived from ‘ought-free’ (non-moral) premises. Morality does not describe the way the world is but how it should be. For example, to define ‘goodness’ as that which brings the greatest pleasure is to commit a logical error (confusing moral judgements (‘ought’) with factual judgements (‘is’)). ‘If I am asked "What is good?", my answer is that good is good and that is the end of the matter. Or if I am asked "How is good to be defined?" my answer is that it cannot be defined and that is all I have to say about it’ Moore’s essential problem is that even if we state that something is ‘good’ it is impossible to explain why this is so: ‘Whatever definition may be offered, it may always be asked…of the complex so defined whether it itself is good’. 15 Where Do You Stand? 16