week_by_week_diary Spring 2009

advertisement

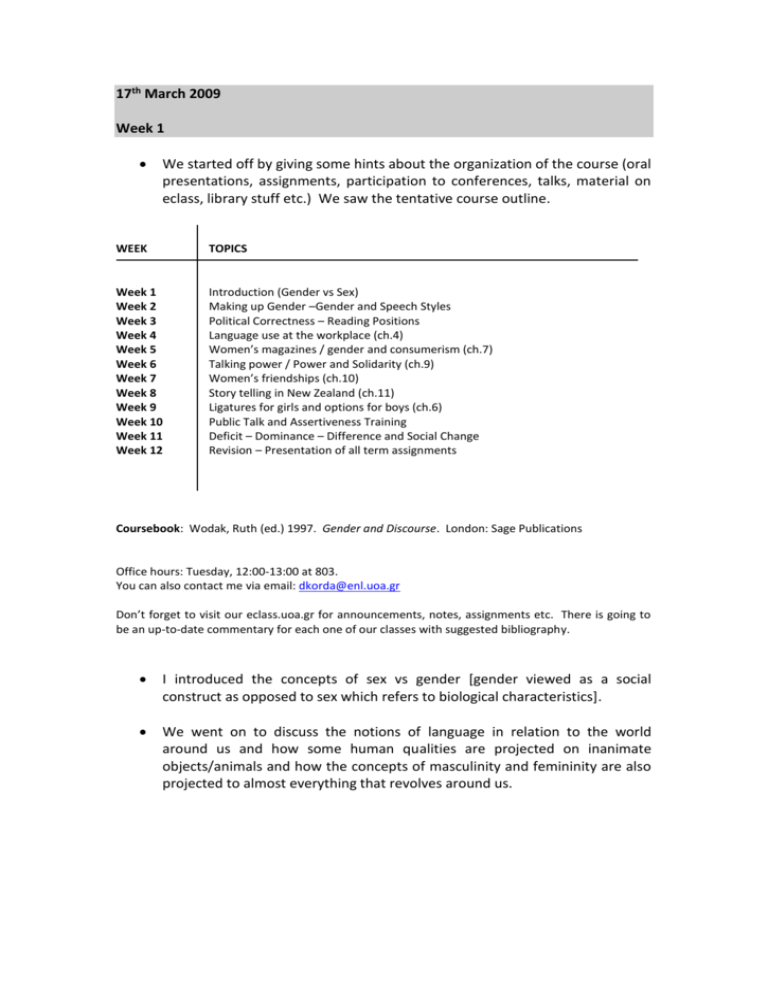

17th March 2009 Week 1 We started off by giving some hints about the organization of the course (oral presentations, assignments, participation to conferences, talks, material on eclass, library stuff etc.) We saw the tentative course outline. WEEK TOPICS Week 1 Week 2 Week 3 Week 4 Week 5 Week 6 Week 7 Week 8 Week 9 Week 10 Week 11 Week 12 Introduction (Gender vs Sex) Making up Gender –Gender and Speech Styles Political Correctness – Reading Positions Language use at the workplace (ch.4) Women’s magazines / gender and consumerism (ch.7) Talking power / Power and Solidarity (ch.9) Women’s friendships (ch.10) Story telling in New Zealand (ch.11) Ligatures for girls and options for boys (ch.6) Public Talk and Assertiveness Training Deficit – Dominance – Difference and Social Change Revision – Presentation of all term assignments Coursebook: Wodak, Ruth (ed.) 1997. Gender and Discourse. London: Sage Publications Office hours: Tuesday, 12:00-13:00 at 803. You can also contact me via email: dkorda@enl.uoa.gr Don’t forget to visit our eclass.uoa.gr for announcements, notes, assignments etc. There is going to be an up-to-date commentary for each one of our classes with suggested bibliography. I introduced the concepts of sex vs gender [gender viewed as a social construct as opposed to sex which refers to biological characteristics]. We went on to discuss the notions of language in relation to the world around us and how some human qualities are projected on inanimate objects/animals and how the concepts of masculinity and femininity are also projected to almost everything that revolves around us. 24th March 2009 Week 2 The first part of the class had to do with the qualities we associate with men and women. We gave examples from adjectives, nouns, adverbs and verbs and we discussed the denotative and connotative meaning of words. All students present had to make lists of terms which they thought would be associated with either men or women or both (with perhaps different connotative meaning, e.g. ‘well built’, hunk, buxom etc.). Another focus of the class was the qualities and attributes that women and men are expected to have in society. After discussion we gradually extended that to include the roles that women and men are expected to have in society. We also explored the ways in which we all circulate these expectations via language and images in many different contexts. Some of the contexts we examined were the home and the school (as early stages of socialization), the world of advertisements and the fictional world of novel and popular fiction. One class assignment set for this week had to do with images and language used for advertisements in toy sections of some popular Christmas catalogues. The second part of the class was concerned with gender and speech styles of men and women alike. The main line of thought focused on old protocols for the linguistic behaviour of women (folklinguistics). We also explored set/fixed phrases (he swears like a trooper or nice girls don’t swear) that reflect the norms governing linguistic behaviour. We also did a few theoretical “journeys” as far back as Otto Jespersen’s book in 1922. He described women’s language as deficient. We went on to account for Robin Lakoff’s theory (1975) about ‘woman’s language’ and continued with Dale Spender’s (1980) ‘man made language’ (male dominance). Finally, we referred to Deborah Tannen’s theory about differences between the two sexes and the gender scripts each one of them has in order to communicate and interact with each other. We used the above authors to investigate how women’s language has been treated in the past and under what circumstances. This will serve as the benchmark against which we can explore some current perspectives on language and gender. Suggested Reading: Goddard, Angela & Lindsey Mean Patterson. 2000. Language and Gender. New York / London: Routledge 31st March 2009 Week 3 Our class started off with some kinds of criticism against the theories presented last time: deficit, dominance, difference. The deficit model can be re-interpreted according to recent linguistic trends. For instance, tag questions (Nice day, isn’t it?) are not considered signs of uncertainty any more but diverse forms of interactive communicative strategies. On top of that, these early theories did not take into account the wider context (social and cultural): much early feminist research was dominated by a white, middle-class, heterosexual, American point of view. As far as the male dominance theory is concerned there was to a certain extent a level of generalization in explanations which didn’t fit with many people’s experience of men and women (e.g. a picture of men conspiring how to do women out of their linguistic inheritance). Of course one of the biggest difficulties was that cultural differences were still not being accounted for. The shift from looking at women either as deficient or oppressed users of language was celebrated by the difference model. However, this move was also criticized because ‘difference’ theorists overlooked the larger sociopolitical context. They were also criticized for not looking at the two sexes as very much unlike different cultures: although we may learn what are appropriate behaviours for our own sex, we also have ideas from very early on about the opposite sex. The main class explored the issue of politically correct language. We made a historical survey of the use of the term over the past 30 years and we saw some attempts to make changes in language use. The liberal approach is meant to effect changes on the use of everyday language (chairman vs chairperson, fireman vs firefighter etc.). The radical approach attempts to either invent new terms for situations which have never been given a name before (to granny) or give old words new meanings (spinster is a spiraling dervish). Students who were present had to experiment with language and be creative in making up new terms for familiar situations which have not been successfully expressed so far (e.g. ‘woo-man’, men as ‘breakers’ etc.) We also discussed issues relating to reading positions and more specifically how written texts position us as readers. Then we went on to explore whether there is gender positioning of the reader. We analysed an advertisement for a playstation game (Zelda). We paid particular attention to some strategies adverts are using in order to attract the narratee’s attention: (a) they present a strong profile of the prospective consumers, (b) they use highly interactive strategies –questions, direct address, (c) they use some forms of intertextuality. For next time, students will collect some texts that hey consider present a strong profile of the narrate (one idea is to look at problem pages in male and female magazines). For extra reading on political correctness (and other topics) you can consult the notes I left at the library. You can also find all the handouts distributed so far. All this stuff is to BE PHOTOCOPIED, NOT TO BE TAKEN AWAY. 7th April 2009 Week 4 Our class started with some practical exercises following the work done during the previous class on texts and how they position us (problem pages from men’s and women’s magazines, advertisements: Gloves for all seasons…) We carried on with a presentation on the use of euphemism (more particularly the use of the word “lady”). The second part of the class constituted a close reading of Ch.4: men and women at the workplace. There was a presentation on how women interact with each other and how they enact authority in the workplace. We also explained the methodological model proposed by Deborah Tannen through the multidimensional grid about Distance-Closeness, Equality-Hierarchy. The rest of the class was a hands-on analysis of women in ‘masculine’ jobs: how they change their gender identity, how the profession they work for changes to accommodate women (police force) and what speech behaviour is involved in such environments. 28th April 2009 Week 5 The main topic of this class was about women’s magazines. We first introduced the idea of consumerism and femininity and then went on with a historical overview of women’s magazines since the early 19th century. In our discussion we included issues like the multiple voices heard in magazines, the construction of consumer femininity, power relations etc. included in Mary Talbot’s book Language and Gender: an introduction (available in our library) Since there was no presentation last time the class was divided into small groups and students analysed a variety of mainstream and alternative women’s magazines. At the end they reported to the rest of the class their findings (be it interesting, striking, odd, ordinary or extraordinary). We thus had the chance to compare different women’s magazines compare women’s with men’s magazines compare all the modern women’s magazines available in class with an old version of Γυναίκα of the year 1957. At the end of the class we discussed some issues mentioned in Chapter 7 of Gender and Discourse by Ruth Wodak, such as some features of women’s magazines that are recurrent (e.g. obsession with appearance, desocialization, multimodality of magazines etc.) We only touched upon the theoretical basis of the research which connects MAK Halliday’s theory of interpersonal , semiotic, ideational functions of language and Basil Bernstein’s theory of elaborated and restricted code. 5th May 2009 Week 6 This time our main aim was to introduce the idea of discourse and especially Critical Discourse Analysis. We had a very close and detailed reading of the introduction in Ruth Wodak’s book Language and Gender. We discussed issues like contextsensitive approaches to gender studies, feministic linguistics, discursive practices and their immediate situational or institutional contexts in society. We opened up the discussion to include Fairclough’s diagram of the conception of discourse as social practice as this is presented by Mary Talbot in her book Language and Gender: an introduction. A Text is embedded in Discursive practices which are also embedded in Social Practice. One practical application of this was the exploration of antenatal discourse and the positioning of women through the use of different language practices. Students present in class resorted to material found in magazines and explored how the medicalization of giving birth to a child is exaggerated and overnaturalised through the use of language. For instance, they discussed in small groups a variety of texts presenting mothers-to-be as patients-to-be. The main aim of such an activity was to use the theoretical framework Text-Discursive practices-Social Practice in a practical way. The main topic of today’s class was Chapter 9 Talking power: Girls, Gender Enculturation and Discource. During this class we had the chance to discuss double voice discourse in girls’ conversations. From an early age girls are aware of the conventions of the speech styles they are supposed to use and they know how to be ‘nice’ and have their own way at the same time. We discussed the findings of Amy Sheldon’s research and then we opened up discussion as to what happens with young boys and girls when they are faced with confrontational discourse. The class was enriched by a research done by Deborah Tannen who investigated physical alignment between boys and girls, men and women when they have intimate conversations. The female friends physically aligned themselves with one another and frequently looked at one another directly. The male friends, especially the younger boys, aligned their bodies and eyes very much less. Topic cohesion was another dimension of the same research which proved that girls/women discuss a variety of topics devoting long periods of time to each one of them, whereas boys/men select fewer topics and only devote a limited amount of time to each one of them. This does not necessarily mean that boys/men are not able to have intimate and sincere conversations among themselves; it’s only that they do it less often and they grow up with different expectations about friendly, conversational behaviour. The class ended with some examples of dialogues between same-sex groups in the playground with girls showing rapport and support and boys displaying their confrontational skills and their eagerness to have leaders for their ‘gangs’. This kind of verbal behaviour may also result to miscommunication between adults who were raised to a certain extent in gender-specific cultures. At the very end of the class we had a look at writing skills which students will find useful when writing their assignments which are going to be announced next week. You can have a look at them in the relevant Lecture Notes area in the eclass. Suggested Reading: Talbot, Mary. 1998. Language and Gender: An Introduction. Oxford: Polity Press (Chapters 1 and 3) Tannen Deborah. 1996. Gender and Discourse. New York and Oxford: Oxford University Press (Chapter 3:Gender Differences in Conversational Coherence) 12th May 2009 Week 7 Today’s focus was women’s friendships. Students had to read chapter 10 of their book, which was an article written by Jennifer Coates. There are 5 linguistic strategies usually employed by women when they are having conversation with other women: repetition, collaborative floor, story-telling, hedges and questions. We discussed and shared our personal experiences of same-sex and mix-sexed friendships. The second part of the class was more practical and data-analysis oriented. We analysed some authentic data collected by Jennifer Coates in another article of her’s: “‘Thank God I’m a woman’: the construction of differing femininities”. The article, enriched by detailed commentary, was included in an edited volume by Deborah Cameron The Feminist Critique of Language (1988) and you can now find a copy of it in our box in the Library. For those of you who are interested in writing an essay, you can find a list of topics on which you can work. Any other ideas are welcome provided you have a word with me first. Suggested Reading: Cameron, Deborah (ed.). 1988. The Feminist Critique of Language. London: Routledge 19th May 2009 Week 8 The class started with a presentation which shed light to the linguistic strategies used by women with their friends and the way these strategies relate to the concept of silence (you can find a copy of this presentation in our box at the library). Story telling was the main topic of our class. We highlighted some important notions from chapter 11 of our book. In order to explore the function of story-telling both in the ways interlocutors interact with one another and in the ways they construct their gender identity we looked at some authentic data from Mary Talbot’s book Language and Gender (1998) Part II. We extended our hands-on experience by two more researches that presented findings relating to narratives at dinner-table by Shoshana Blum-Kulka and child socialization through narrative practices by Ochs and Taylor. Suggested Reading: Talbot, Mary.1998. Language and Gender. An Introduction. Oxford: Polity Press (Part II, photocopy from Telling stories) 26th May 2009 Week 9 The main focus of this class was gender in the educational setting. We explained ligatures and options from David Corson’s article in the course book (chapter 6). We enriched the class with two articles from Sara Mills’ edited book Language and Gender. Interdisciplinary Perspectives (1995). The articles were about teachers’ and students’ perspectives of how the two sexes are treated in the English class. We added a third research conducted by Sadker & Sadker about gender in the American educational system. In the second part of the class we worked on a variety of projects done in Greek high schools in order to sensitize students, parents and teachers about gendered stereotyping which is prevalent in the greek society. Suggested Reading: Altani, Cleopatra 1995 ‘Primary school teachers’ explanations of boys’ disruptiveness in the classroom: a gender-specific aspect of the hidden curriculum’ pp 149-159 in Sara Mills (ed) Language and Gender, Harlow and New York: Longman Sunderland, Jane 1995 ‘”We’re boys, miss!” finding gendered identities and looking for gendering of identities in the foreign language classroom’ pp 160-178 in Sara Mills (ed) Language and Gender, Harlow and New York: Longman Myra, Sadker, David, Sadker, Lynn Fox & Melinda Salata 2004 “Gender Equity in the Classroom: The Unifinished Agenda” pp 220-226 in Michael Kimmel (ed) The Gendered Society Reader, Oxford: Oxford University Press 2nd June 2009 Week 10 The main topic of the class was women and the public talk. More specifically, we discussed how women are actually (under)represented in the media and in their use of public talk. We examined women as users of Computer Mediated Communication. There was a student presentation on media discourse and how the same piece of news can be ‘resignified’ depending on journalists’ ideological background. Then we discussed the case of the female leader of the Northern Ireland Women’s Coalition (NIWC) and the treatment she received by the members of the Irish Parliament and the media of her country. In the second part of the class we discussed training sessions on being assertive and their effects on the feminist movement. We started off with some warm up exercises on assertive and non-assertive behaviour. We discussed research included in Mary Crawford’s book Talking Difference On Gender and Language (1995) and we found out that “the assertiveness training [became] a virtual panacea for women’s problems which was recommended for almost everything: identity loss in newly married women, super mother syndrome, mid-life depression, depression due to loss, psychological problems in job settings, psychosomatic illness, drug/alcohol abuse, and agoraphobia.” We concluded that this trendy movement was there to just help editors market their books in the best possible way. “The assertiveness training movement functioned to deflect attention from the fact that women are over-represented in low-power, low-status social roles and situations. It constitutes an example of ‘woman-as-problem’ thinking in which women are blamed for the consequences of their low social status. Even more important, it illustrates how such thinking can contribute to the continued powerlessness of women by channeling energy into individual change efforts rather than collective action.” Suggested Reading: Talbot, Mary.1998. Language and Gender. An Introduction. Oxford: Polity Press (Part II, Public talk, Talking on the net: computer-mediated communication) Walsh, Clare. 2001. Gender and Discourse. London: Longman Crawford, Mary. 1995. Talking Difference. On Gender and Language. London: Sage Publications (Unit 3 The Assertiveness Bandwagon) 9th June 2009 Week 11 Our class consisted of a student presentation on problematizing the theories of dominance and difference. The discussion that ensued was rather theoretical and we ended up with some practical applications of theory. We read a dialogue and we interpreted the same data from discernibly different theoretical perspectives. The conclusion we reached was that we need a multi-dimensional view of gender and language instead of monolithic theories that overemphasize one aspect to the detriment of another. Suggested Reading: Talbot, Mary.1998. Language and Gender. An Introduction. Oxford: Polity Press Littoseliti, Lia. 2006. Gender and Language. London: Hodder Arnold 16th June 2009 Week 12 This was the last class we had and it was mainly a revision class. We covered roughly all the topics we had discussed in class and answered questions relating to the style of the exam which is going to be both practical and theoretical. In terms of the material covered during the first 3 weeks (basically stuff from Angela Goddard’s book Language and Gender)we could summarize it as follows: o Language is not a neutral reflection of the world around us, but by using language, we project onto the world our own sense of ‘reality’. Starting with the idea that different languages encode objects and ideas differently, we went on to look at two specific types of projection: the projection of humanness onto the inanimate world; the projection of gender onto the inanimate and the animal worlds. o Then we looked at the qualities and attributes that women and men are expected to have, and the way in which we circulate these expectations via language and images in many different contexts. o The next issue we discussed was the ways in which our language is far from neutral. Although the relationship is complex, you should now have some understanding of the way in which language embodies our cultural and social values and the way we invoke these automatically in our thinking. It should be clear that language is not a direct reflection of any natural order but a daily enactment of a social one. This means that when we speak, we don’t just say words, we speak our culture. o In breaking down what is meant by the term ‘political correctness’, two different types of language use were identified as commonly being labeled under this heading: o o new language items that have been suggested by liberal critics, for use in real contexts; new language items that nave been created by radical critics, in order o reveal prevalent ideologies, but not necessarily for everyday use. o It was suggested that the term ‘political correctness’ itself was typically used by people who object to language reform per se, and who would classify all the examples above as wrongful and misguided uses of English. o Last, there was a brief introduction to text analysis, applying to everyday texts (e.g. advertisements) some of the ideas about gender and connotations, cognitive models and social knowledge. The second part of the class was devoted to small presentations on the part of the students who had completed their assignments. They shared with us their initial research questions and their findings. Course evaluation came last (which was overall positive. Thank you!).