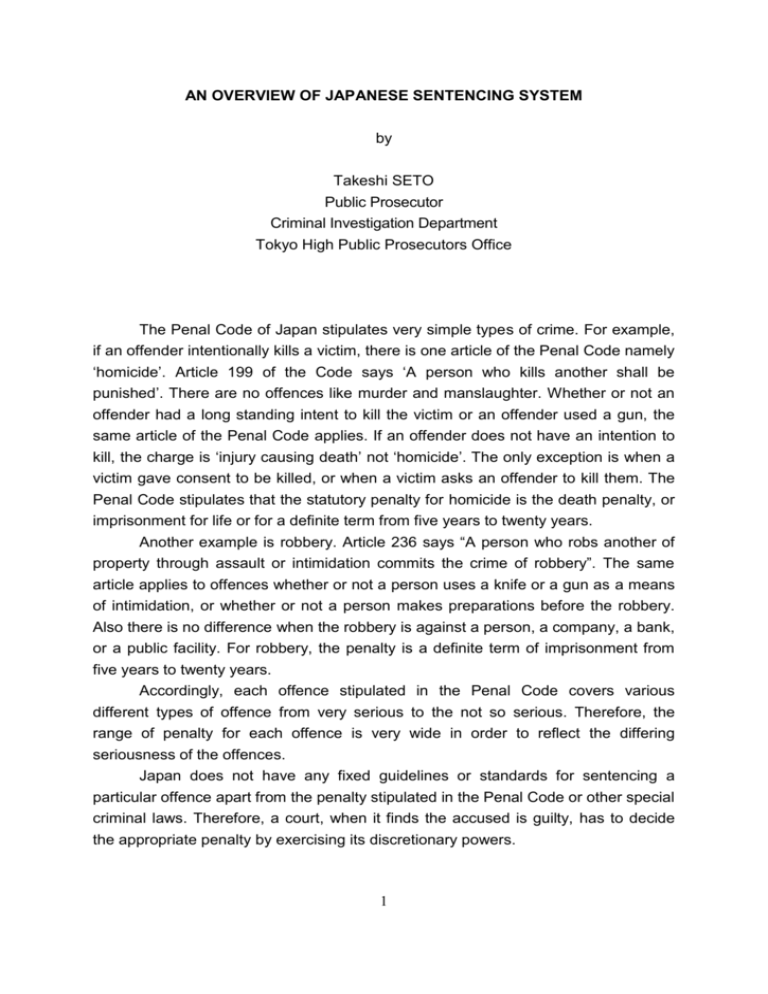

AN OVERVIEW OF JAPANESE SENTENCING SYSTEM

by

Takeshi SETO

Public Prosecutor

Criminal Investigation Department

Tokyo High Public Prosecutors Office

The Penal Code of Japan stipulates very simple types of crime. For example,

if an offender intentionally kills a victim, there is one article of the Penal Code namely

‘homicide’. Article 199 of the Code says ‘A person who kills another shall be

punished’. There are no offences like murder and manslaughter. Whether or not an

offender had a long standing intent to kill the victim or an offender used a gun, the

same article of the Penal Code applies. If an offender does not have an intention to

kill, the charge is ‘injury causing death’ not ‘homicide’. The only exception is when a

victim gave consent to be killed, or when a victim asks an offender to kill them. The

Penal Code stipulates that the statutory penalty for homicide is the death penalty, or

imprisonment for life or for a definite term from five years to twenty years.

Another example is robbery. Article 236 says “A person who robs another of

property through assault or intimidation commits the crime of robbery”. The same

article applies to offences whether or not a person uses a knife or a gun as a means

of intimidation, or whether or not a person makes preparations before the robbery.

Also there is no difference when the robbery is against a person, a company, a bank,

or a public facility. For robbery, the penalty is a definite term of imprisonment from

five years to twenty years.

Accordingly, each offence stipulated in the Penal Code covers various

different types of offence from very serious to the not so serious. Therefore, the

range of penalty for each offence is very wide in order to reflect the differing

seriousness of the offences.

Japan does not have any fixed guidelines or standards for sentencing a

particular offence apart from the penalty stipulated in the Penal Code or other special

criminal laws. Therefore, a court, when it finds the accused is guilty, has to decide

the appropriate penalty by exercising its discretionary powers.

1

No prosecution

A public prosecutor in Japan has discretion not to prosecute a case, even

though the evidence is sufficient to secure a conviction. This system can be

recognized as one of the safety measures. Article 248 of the Code guides a public

prosecutor through the exercise of his or her discretionary power of non-prosecution.

Article 248 explains “Where prosecution is deemed unnecessary owing to the

character, age or environment of the offender, gravity of the offense, circumstances

or situation after the offense, prosecution need not be initiated.” These elements can,

however, also guide a court to find aggravating and mitigating factors in sentencing.

So the list includes three parts: offender, crime and other factors.

The Standard of Proof for Sentencing

As in other countries, the standard of proof for conviction is “beyond

reasonable doubt”. However, it is not necessary that aggravating and mitigating

factors are proved to the same standard. Further the admissibility rules, which apply

to the evidence for conviction, do not apply to the evidence which relates only to

aggravating and mitigating factors.

Unlike the Anglo-American legal system, which has two separate stages for

adjudication, namely conviction and sentence, Japan combines these two stages

into one, like the systems in Continental Europe. So Japan does not have a special

procedure for finding or gathering elements for sentencing, after conviction.

Therefore, the court examines evidence to prove guilt and to determine the

appropriate sentence during the same trial procedure. So the crucial elements for

deciding sentence are included in evidence for the conviction. By reason of this,

evidence concerning aggravating and mitigating factors is usually dealt with in the

same manner as other fact-finding evidence. Although the court does not use the

same standards applied for convictions, it uses nearly the same standards.

AGGRAVATING AND MITIGATING FACTORS

The seriousness of the offence is assessed by factors which include:

the motivation or purpose of offence,

the planning,

the number of victims,

the cruelty of the crime,

the extent of injuries,

2

the amount of financial damage etc.

the possibility of copy-cat crime and

the harmful effect to local residence or society.

These are evaluations on crime itself and closely relate to retributive aspect in

sentencing. The court focuses on the offender with the focus on rehabilitation.

Examples

For example, if the character of an offender charged with assault, is

aggressive, a court may consider him or her to be a dangerous person and find a

high risk of reoffending. Similarly, principles apply when the thief is considered to be

lazy or chooses or is forced to leave his or her job. Young offenders are usually

regarded as amenable to rehabilitating and presumed not to re-offend again.

Environmental factors of the offender which are considered include whether he or

she has a family or a supervisor, or whether he or she has a steady job.

Other factors include apologies to the victim; the recovery of damage; the

possibility of a settlement out of court; remorse; recidivism by an offender; the

criminal history of the offender; participation in a criminal organisation, the

relationship with other offenders and co-operation with the investigating authorities.

Alcohol

If the offender commits a crime under the influence of alcohol and he or she

could easily have avoided such a situation by managing how to drink alcohol, this

fact may lead to more severe sentences. However it may not be a crucial element for

sentencing. In practice, the defence side usually raise this factor to plead insanity or

diminished capacity of the offender, by which the offender is not punishable or the

statutory penalty can be reduced. However such claims are rarely accepted by a

court.

Sexual abuse of children

In Japan, if a person commits sexual intercourse or other indecent acts with a

person under thirteen years old, he or she is charged with rape or other sex offences

even though the victim gives their ‘consent’. The range of statutory penalties are the

same for victims aged under thirteen and those aged thirteen or over. Where victims

are particularly young so they cannot easily recover from their trauma and the

suffering there is harsh punishment.

REDUCING SENTENCES

3

The Penal Code permits reductions from statutory maximum penalties, if one

of the conditions in the code is found. These conditions include:

a) diminished capacity of an offender,

b) voluntary abandonment of commission of the crime,

c) the offender is an accomplice who is therefore an accessory to the crime and

d) voluntary surrender to the police.

The court also has a discretion to make reductions under Article 66 of the

Penal Code which says “Punishment may be reduced in light of the extenuating

circumstances of a crime.”

However the court discretion to reduce penalties is fettered. If a court reduces

the sentence outside the range in the code’s framework, the sentence is illegal and

should be quashed by the high court upon appeal.

The rules for reduction of sentence in the Penal Code are as follows;

i)

The death penalty is reduced to imprisonment for life or for a definite

term from ten to thirty years.

ii)

Imprisonment for life is reduced to imprisonment for a definite term

from seven to thirty years.

iii)

Imprisonment for a definite term is reduced by half.

iv)

Fines are reduced by half.

UNIFORMITY IN SENTENCING

The Judiciary has also started to establish a database on sentences. This is because

the judiciary does not want to use databases which have been prepared by one of

the parties in the trial, namely prosecution service. The database is used to show the

general public what kinds of penalties have been imposed in similar cases. But a

court never says it will follow the sentences in similar cases. This is because a court

places equal importance on both the special features of a case and seeking

uniformity of sentence. Although a court gives information on similar cases as

reference, a court would like the general public to express their common sense on

sentence, which is the one of the reasons for the introduction of the saiban-in

system.

THE PROSECUTOR’S SENTENCING RECOMMENDATION

4

The public prosecutor, as the representative of the public interest,

recommends appropriate sentences to ensure uniformity of sentence. The

recommendation is made at the end of his public prosecutor’s closing argument.

There are no definite rules to assist the prosecutor. However, for relatively minor or

common crimes like road traffic offences, simple possession of drugs and traffic

accidents causing death or injury through negligence, the prosecutor can easily

assess the appropriate sentence because Japan has many similar cases and

therefore precedents have developed. For such offences, prosecutors select the

factors like the type of crime, the defendant’s criminal history, the damage or injury

caused, whether the intention was a specific intent or negligence, the dangers posed,

and the amount of drug found or trafficked.

For more serious crimes such as homicide, robbery, rape and arson, it is

more difficult to evaluate all the factors, because factors like the intention or the

motivation of crime, cruelty involved, the techniques used or damage caused by the

crime vary considerably. The cases cannot be so easily categorised but experience

assists but the public prosecutor refer to the previous judicial precedents by using

their data base. In the past, each public prosecutors office stored its own judgements.

Major public prosecutors offices, such as Tokyo and Osaka distributed their own

data to other public prosecutors offices for reference. These are very useful

materials for knowing the sentencing tends in other parts of Japan. The Japanese

prosecution service has now started to establish databases for all sentences for all

crimes around Japan.

If there are important aggravating or mitigating factors in the case, which

make the appropriate sentence outside the normal range a public prosecutor does

not hesitate to seek the sentence beyond the normal range.

As the recommendation for the sentence by a public prosecutor strongly

influences the court, public prosecutors have to seek approval from his or her

supervisor to ensure appropriate recommendations are given. Death penalty or life

imprisonment cases are given very careful consideration.

The court considers the submissions made by the defence counsel. The

recommendation by a public prosecutor does not bind the court. Sometimes more

severe sentences are passed but generally the court usually passes a lesser

sentence than the one recommended by the public prosecutor. It has been estimated

that courts pass sentences which are about 70 to 80% of term recommended by a

public prosecutor. This practice seems to be accepted by public. However divergence

5

varies.

THE ‘SAIBAN-IN’ SYSTEM and VICTIM REPRESENTATION

In May 2009, Japan started a new criminal justice system called the

“Saiban-in” system. This is a lay-judge system. Under this system the general public

are able to participate in trials of certain serious criminal cases as saiban-in. The panel

of judgement consists of three professional judges and six members of the general

public. They both have equal authority to decide whether the accused is guilty or not

and what kind of sentence is appropriate. One of the reasons for introducing this

system is to reflect the reliable common sense of the general public in trial decisions.

So far, the average of the sentences imposed is not very different from the sentences

judges impose previously.

The other new system is the participation of victims or their bereaved family in

criminal proceedings. Previously, a victim or his or her bereaved family could

express their suffering during the trial. Also a victim or his or her bereaved family has

the possibility to attend the trial and make a closing argument including making

recommendation about the sentence. Since such a victim or bereaved family directly

explains the damage and feeling on the crime and expresses opinion on the

sentence to a court, sentence is becoming harsher than before especially for crimes

of sexual abuse and traffic accident causing death or injury through negligence.

The two new systems, namely saiban-in system and participation of victims,

may change the current practice of sentencing. However, because there was no

strong opposition against the former practice, many think the current practice should

be kept our practice for the moment.

APPEALS

If the public prosecutor considers the sentence is too lenient, he or she may

appeal the sentence to the High Court. When deciding whether or not to appeal, a

prosecutor has a meeting with his or her colleagues and supervisors and will

consider the judicial precedents. Generally, a public prosecutor respects the

discretionary power of the court but seeks uniformity of sentence.

The defence can also appeal the sentence. For the prosecution service, if the

6

sentence is about half or even less than the recommendation, public prosecutors

seriously consider appealing. The same applies where a court does not follow the

recommendation of death penalty or life imprisonment.

About the Author

Takeshi Seto has been a public prosecutor of Japan for more than twenty years

working for the Justice Ministry of Japan

Thanks

Robert Banks is very grateful to Takeski Seto for providing this overview.

7