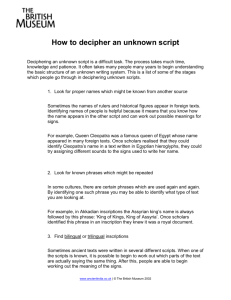

Writing an unwritten language

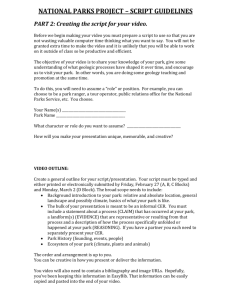

advertisement