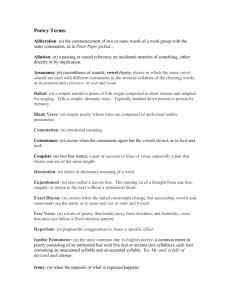

Literary terms

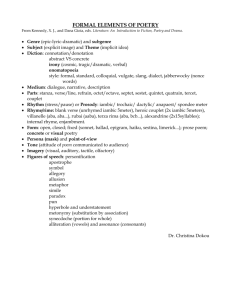

advertisement

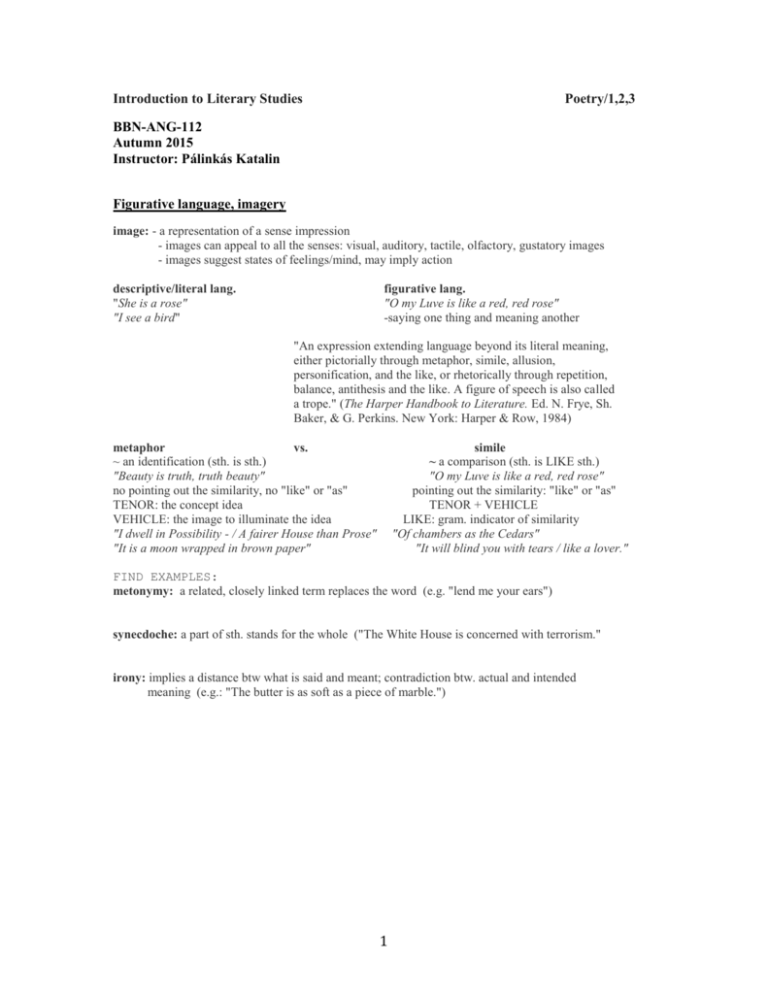

Introduction to Literary Studies Poetry/1,2,3 BBN-ANG-112 Autumn 2015 Instructor: Pálinkás Katalin Figurative language, imagery image: - a representation of a sense impression - images can appeal to all the senses: visual, auditory, tactile, olfactory, gustatory images - images suggest states of feelings/mind, may imply action descriptive/literal lang. "She is a rose" "I see a bird" figurative lang. "O my Luve is like a red, red rose" -saying one thing and meaning another "An expression extending language beyond its literal meaning, either pictorially through metaphor, simile, allusion, personification, and the like, or rhetorically through repetition, balance, antithesis and the like. A figure of speech is also called a trope." (The Harper Handbook to Literature. Ed. N. Frye, Sh. Baker, & G. Perkins. New York: Harper & Row, 1984) metaphor vs. ~ an identification (sth. is sth.) "Beauty is truth, truth beauty" no pointing out the similarity, no "like" or "as" TENOR: the concept idea VEHICLE: the image to illuminate the idea "I dwell in Possibility - / A fairer House than Prose" "It is a moon wrapped in brown paper" simile ~ a comparison (sth. is LIKE sth.) "O my Luve is like a red, red rose" pointing out the similarity: "like" or "as" TENOR + VEHICLE LIKE: gram. indicator of similarity "Of chambers as the Cedars" "It will blind you with tears / like a lover." FIND EXAMPLES: metonymy: a related, closely linked term replaces the word (e.g. "lend me your ears") synecdoche: a part of sth. stands for the whole ("The White House is concerned with terrorism." irony: implies a distance btw what is said and meant; contradiction btw. actual and intended meaning (e.g.: "The butter is as soft as a piece of marble.") 1 Rhythm, metre and rhyme Sources: SLIDES for the Introduction to Literary Studies lecture (SEAS) Poetry Foundation, Glossary of Terms (Rhythm & Meter) Derek Attridge: Poetic Rhythm. An Introduction (Cambridge UP) FIND OTHER EXAMPLES: rhyme: full rhyme: "fears" - "years" slant/half/near/off rhyme gives an approximation of sounds: "cat" - "cot" eye rhyme: "This" - "Paradise" + internal rhyme + rhyme scheme: cross rhyme, couplet alliteration assonance rhythm (and metre): Rhythm is based on orderly repetition. Rhythm creates a pattern of recurrence and difference. Rhythm in a more general sense (rhythmic movement of everyday activities) could be defined as a "patterning of energy . . . a series of alternations of build-up and release, movement and counter-movement, tending toward regularity but complicated by constant variations" (Attridge, 3). Rhythm is "what makes a physical medium (the body, the sounds of speech or music) seem to move with deliberateness through time, recalling what has happened (by repetition) and projecting itself into the future (by setting up expectations)" (Attridge, 4). All languages have their distinctive rhythms. Poetry exploits and heightens the rhythms characteristic of a given language. In order to appreciate the rhythm of poems, you have to read them out. Attridge states that "[r]eading poetry requires time; each word needs to emerge and fulfill itself before we go on to the next. A poem is a real-time event" (2). "Poetry takes place in time; its movement through time, more or less regular is its rhythm" (Attridge, 19). Prose rhythm: prose may use repetitions, parallels of words, syntactical units, grammar structures, sentence length, semantic structures to create a distinctive rhythm. However, prose does not follow any preset pattern. In comparison, poetic rhythm relies on predictable and repetitive structures of sound patterning. Poetic rhythms call attention to themselves. Poetic rhythm is based on the regular alternation of certain syllabic features of the text. Verse is a patterned succession of syllables: some are strongly emphasized, some are not. Most poetry is written in verse, either in metrical verse or in nonmetrical free verse. (Free verse is "free" from traditional metrical and stanzaic patterns, but it employs various other structures which produce rhythm: sound and image repetitions, parallelism, line-end pauses, etc.) In poetry, metre is the basic rhythmic structure of a verse or lines in verse. Many traditional verse forms prescribe a specific verse meter, or a certain set of meters alternating in a particular order (e.g.: ballad metre, blank verse). Attridge's definition for meter: "Meter is an organizing principle which turns the general tendency toward regularity in rhythm into a strictly patterned regularity that can be counted and named" (7). E.g.: COMMON METER OR BALLAD METER: a quatrain (four-line stanza) in iambic meter, alternating lines of 4 and 3 stressed syllables, rhyming abcb or abab It is used with perfect regularity in Wordsworth's "A Sumber Did My Spirit Seal": A slumber did my spirit seal; I had no human fears: She seemed a thing that could not feel 2 The touch of earthly years. stress, accent, beat: (SLIDES) Stress commonly is a conventional label for the overall prominence of certain syllables relative to others within a linguistic system. In this sense, stress does not correlate simply with loudness, but represents the total effect of factors such as pitch, loudness and duration. English, sometimes described as a ‘stress timed’ language, makes a relatively large difference between stressed and unstressed syllables, in such a way that stressed syllables are generally much longer than unstressed. English poetic rhythm is based on the regular alternation of stressed and unstressed syllables. Stresses are that of words stresses and marked in dictionaries by ‘ as in synecdoche /sɪ’nɛkdəkɪ/. (The term accent is sometimes used loosely to mean stress, referring to prominence in a general way or more specifically to the emphasis placed on certain syllables.) Beat denotes stress with metrical relevance, i.e. stressed syllables which count in metrical lines are called beats. Scansion is the act of determining and graphically representing the metrical character of a line of verse. Stressed syllables are marked by the symbols / or – Unstressed syllables /slacks are marked by the symbol x When I consider how my light is spent x / x / x / x / x / Whose woods these are I think I know x / x / x / x / (Milton) (Frost) Types of metre: Accentual verse/ Stressed meter Verse whose meter is determined by the number of stressed (accented) syllables—regardless of the total number of syllables—in each line. Many Old English poems, including Beowulf, are accentual; see Ezra Pound’s modern translation of “The Seafarer.” Traditional nursery rhymes, such as “Pat-a-cake, pat-a-cake,” are often accentual. (Poetry Foundation) Sing a song of sixpence, / / / A pocket full of rye; / / (p) Four and twenty blackbirds / / / Baked in a pie. / / (p) = pause Ballad metre is a form of poetry that alternates lines of four and three beats, often in quatrains, rhymed abab. The anonymous poem Sir Patrick Spens demonstrates this well. (The alternating sequence of four and three stresses is called common measure when used for hymns. ) (PF) The king sits in Dumfermline town. / / / / Drinking the blude-red wine: / / / 3 'O whare will I get a skeely skipper, / / / / To sail this new ship of mine?' / / / Accentual-syllabic verse Verse whose meter is determined by the number and alternation of its stressed and unstressed syllables, organized into feet. From line to line, the number of stresses (accents) may vary, but the total number of syllables within each line is fixed. The majority of English poems from the Renaissance to the 19th century are written according to this metrical system. (Poetry Foundation) E.g. Iambic pentameter: five-stress iambic lines When I do count the clock that tells the time (Shakespeare: Sonnet12) x / x / x / x / x / iamb or iambic foot: x / trochee or trochaic foot: / x anapaest or anapaestic foot: x x / dactyl of dactylic foot: / x x spondee or spondaic foot: / / monometer: one foot dimeter: two feet trimeter: three feet tetrameter: four feet pentameter: five feet hexameter: six feet Blank verse is unrhymed iambic pentameter, also called heroic verse. This 10-syllable line is the predominant rhythm of traditional English dramatic and epic poetry, as it is considered the closest to English speech patterns. Poems such as John Milton’s Paradise Lost, Robert Browning’s dramatic monologues, and Wallace Stevens’s “Sunday Morning,” are written predominantly in blank verse. 4 Genres: For brief explanations use the Glossary Terms of Poetry Foundation: http://www.poetryfoundation.org/learning/glossary-terms?category=forms-and-types Poetry Elegy Epistle Ode Song Folk song Pastoral etc. Kind Drama Genre Tragedy Comedy Morality Miracle Fiction Novel Short story Romance etc. Sub-genre Revenge Comedy of manners Picaresque / Epistolary / Utopia / Detective Genres of narrative poetry: Narrative poetry is poetry with a plot. Narrative poems can be short or long. Examples: epic poem, mock heroic, romance, novel in verse, ballad, etc. Ballad: A narrative poem in short stanzas, with or without music. The term derives from the French ballade, "to dance," and once meant a simple song that accompanied a dance. Over time ballads lost their direct association with dance, but they kept their strong rhythms. We can distinguish three major types: the traditional ballad (folk or popular ballad), a song of anonymous authorship, transmitted orally; the broadside ballad, printed and sold on single sheets; and the literary ballad, an imitation of the traditional ballad. Interest in the traditional ballad as literature began in Great Britain in the eighteenth century. The first collection was Thomas Percy's Reliques of Ancient English Poetry (1765). Other famous collections: Sir Walter Scott: Minstrelsy of the Scottish Border (1802); Francis J. Child: English and Scottish Popular Ballads (5 volumes, 1882-1898, known as the Child Ballads). Common themes and figures: historical events and legendary figures; the belief of the community and supernatural beings; murder and outlaws; death and unhappy love, etc. Traditional ballads share important formal characteristics. The most common stanza is the ballad stanza: four lines, alternating iambic tetrameter and iambic trimeter in a 4/3/4/3 pattern, rhyming on the second and fourth lines (rhyme scheme: abcb). Ballads often have refrains and use repetition to build up their narrative. Typically, the plot is developed elliptically, as if a longer tale would have been stripped by repetition of all but its essential elements. Speakers appear without introduction and often there is no transition between speakers. Language is archaic and formulaic, with phrases repeated. Wordsworth's lyrical ballads also often report incidents, use ellipsis and repetitions, but the emphasis is shifted from narrative development to the expression of powerful emotions. (Source: Northrop Frye et al.: The Harper Handbook to Literature (1985)) Genres of Lyric Poetry: Lyric poems are often brief and emphasize sound and pictorial imagery rather than narrative or dramatic development. The origins of lyric go back to Ancient Greece: lyric poems were sung to they lyre. Lyric later came to be associated with the intense expression of personal feelings. Genres of lyric poetry: song, sonnet, ode, elegy, epistle, epitaph, etc. Song: A musical composition for one or several voices, which may or may not be accompanied by musical instruments. In poetry songs often have tunes (e.g. Burns, or John Donne's "Song") but the text can also be 5 appreciated without its musical setting. Songs typically present an intense and clear emotional stance. Sonnet: A 14-line poem with a variable rhyme scheme originating in Italy and brought to England by Sir Thomas Wyatt and Henry Howard, Earl of Surrey in the 16th century. Literally a “little song,” the sonnet traditionally reflects upon a single sentiment, with a clarification or “turn” of thought in its concluding lines. The Petrarchan sonnet, perfected by the Italian poet Petrarch, divides the 14 lines into two sections: an eight-line stanza (octave) rhyming abbaabba, and a six-line stanza (sestet) rhyming cdcdcd or cdeede. John Milton’s “When I Consider How my Light Is Spent” and Elizabeth Barrett Browning’s “How Do I Love Thee” employ this form. The Italian sonnet is an English variation on the traditional Petrarchan version. The octave’s rhyme scheme is preserved, but the sestet rhymes cddcee. See Thomas Wyatt’s “Whoso List to Hunt, I Know Where Is an Hind.” Wyatt and Surrey developed the English (or Shakespearean) sonnet, which condenses the 14 lines into one stanza of three quatrains and a concluding couplet, with a rhyme scheme of ababcdcdefefgg. (Source: Glossary of Terms, Poetry Foundation) Ode: A long, stately lyric poem with an elaborate stanza structure. It experesses lofty thoughts and sentiments and is marked by formality in both tone and style. It is a ceremonious poem. We can distinguish two basic kinds: the public and the private. The public ode is used for ceremonial occasions, such as funerals, birthdays, state events, etc. (eg. Andrew Marvell’s "An Horatian Ode upon Cromwell's Return from lreland" (1650)). The private ode celebrates personal and subjective occasions and tends to be reflective and meditative in tone (eg. John Keats's "Ode to a Nightingale"). 6