Burke (1990) - Michigan State University

advertisement

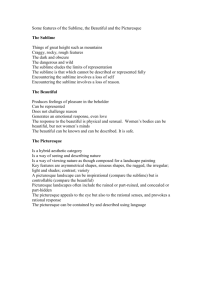

The Rebirth of Cool 1 THE REBIRTH OF COOL: TOWARD A SCIENCE SUBLIME E. David Wong. Ph.D. Dr. Wong is an associate professor in the program of Educational Psychology and Educational Technology in the College of Education at Michigan State University Abstract In this essay, I examine the “cool” and its potential relationship to powerful learning experiences in science education. For most readers, “cool” may seem out of place in academic discourse because it is such an everyday, spontaneous, emotional term. I argue that it is precisely because it natural, common description of something engaging that make the idea of the “cool” worthy of our attention. I begin by highlighting connections between what students call the cool and what artists and philosophers call the sublime. I propose that cool and sublime experiences overlap in three important ways: both can refer to experiences that evoke the chill of being in the presence of the awesome, the thrill of gaining insight into something of transcendent quality, and the sense of connection and harmony with one’s surrounding world. My analysis of these shared qualities draws on work spanning the educational ideas of Dewey and Jackson, the aesthetic philosophy of Burke and Kant, literature from the Romantic period, and the first hand accounts of scientists. By highlighting the surprisingly substantial connection between the cool and sublime, I not only bring greater depth of meaning to the term “cool”, but also build a case for how cool experiences can be taken seriously by educators. In the middle section, I describe how the three kinds of sublimely cool experiences might be created in the classroom. In this “science sublime” curriculum, the 1 The Rebirth of Cool 2 aim is to educate the students’ sensibility and to increase the likelihood, intensity, and meaning of sublimely cool experiences for them. Throughout, I take care to emphasize that not all cool experiences are sublime, and more importantly, cool experiences are not necessarily educative. Educationally worthwhile experiences have subject-matter ideas at the center and are characterized by an expansion of meaning and value for the students. In the last section, I discuss the challenges of having sublime experiences, especially the quieter, subtler experiences. I also describe two intriguing issues: how the sublime may necessarily exceeds our intellectual grasp, and how experience and knowledge may be the enemies of sublime experiences. 2 The Rebirth of Cool 3 THE REBIRTH OF COOL: TOWARD A SCIENCE SUBLIME We love and hate the cool. As educators, few things are more coveted than being recognized as teaching the “coolest” class in the school. We look forward to the rare moments when students gasp in awe or scream in amazement as we teach. However, in the quiet that returns after the last student rushes out the classroom door, we may feel an uneasy ambivalence. Perhaps, we admonish ourselves that serious science is substantial, enduring, and intellectual. We wonder whether our “cool” class was merely superficial, fleeting, and mindless. In this essay, I examine the cool – this idea we love and hate – and assert its importance in science education. I acknowledge that some experiences can be engaging, but are superficial and unimportant – this is the merely cool. I propose, though, that there are also powerful and deeply significant experiences – this is the sublimely cool. I draw from philosophy, literature, psychology, and aesthetics to highlight a connection between cool and sublime experiences. My intent is to describe different kinds of sublimely cool experiences and, thus, bring greater descriptive power to this imprecise, but honest, term. I delve into the meanings of cool and sublime to find useful ways of describing salient qualities of worthwhile educational experiences. I also define sublimely cool experiences in science as having a direct relationship with subject-matter understanding. It is true that the full meaning of aesthetic experiences extends beyond the grasp of words and conceptualization; however, it is equally true that knowledge and reason are central to all worthwhile experiences. The expansion of meaning and perception, not just the arousal of emotion, is the heart of the sublime. 3 The Rebirth of Cool 4 Nobel laureate Richard Feynman makes this point in his comments on the arbitrary distinction between art and science: Poets say science takes away from the beauty of the stars - mere globs of gas atoms. Nothing is "mere". I too can see the stars on a desert night, and feel them. But do I see less or more? The vastness of the heavens stretches my imagination stuck on this carousel my little eye can catch one-million-year-old light.1 Cool as a Sign of Compelling Experience “Cool” is an intriguing expression for it is at once crude and incisive. On the one hand, cool is a common term used by people of all ages and backgrounds in many contexts to describe many things. So wide is its use, cool may seem trite and banal. Cool is rarely chosen carefully in its usage: indeed, cool is more often an unintentional, reflexive utterance. The more one thinks before speaking, the less likely “cool” will be used. Dewey made a similar point in his observation of the word “beauty.” Beauty…is properly an emotional term, though one denoting a characteristic emotion. In the presence of a landscape, a poem or a picture that lays hold of us with immediate poignancy, we are moved to murmur or to exclaim "How beautiful." The ejaculation is a just tribute to the capacity of the object to arouse admiration that approaches worship.2 Dewey then described how the meaning of “beauty” has, unfortunately, been hypostatized and has lost its value to aesthetic theoreticians. Beauty is at the furthest remove from an analytic term, and hence from a conception that can figure in theory as a means of explanation or classification. 4 The Rebirth of Cool 5 Unfortunately, it has been hardened into a peculiar object; emotional rapture has been subjected to what philosophy calls hypostatization, and the concept of beauty as an essence of intuition has resulted. For purposes of theory, it then becomes an obstructive term.3 It seems that beauty and cool share a certain “taken for granted” quality that has caused the “serious-minded” among us to discount its value to our work. However, there are many reasons to not discard these terms to the junk heap of overused, under-defined constructs. The main reason for the “rebirth of cool” is this: when the term cool is evoked, we are expressing something fundamentally genuine and important about our human experience. When “cool” is spontaneously evoked, we are responding in a crude, but sincere way to something compelling. With our unreflective minds and thick tongues, we are saying that we have sensed something significant. We are trying our best to express the inexpressible. We are trying to put words to ephemeral phenomena such as an overwhelming awe, a delicate connection, a dawning insight, or an unexpected inspiration. For example, the experience of seeing the Grand Canyon may be described as “cool” because we get a sense for the vast power of geologic forces. Or, a ride the Top Thrill Dragster roller coaster at Cedar Point Amusement Park may be cool because we are awakened to realize what it means to be vital and alive (perhaps, after being scared to death). We may describe a public figure or fictional character as cool because in them we catch a glimpse of an aspect of human capacity developed to its fullest. The meanings and significance of these experiences are sensed, rather than rationally derived and 5 The Rebirth of Cool 6 cannot be fully articulated within the limited range of language. Thus, we say, “cool.” The word is simple, but the experience it describes can be profound. The Cool and the Sublime The term “cool” probably originated in the world of jazz slang. In the mid-1940’s, a new breed of jazz music called bebop was emerging. Led by Charlie Parker and Dizzy Gillespie, bebop was a musical revolt against the tradition made popular by Louis Armstrong twenty years earlier. Armstrong’s group was called “Louis Armstrong and His Hot Five” (later expanded to the “Hot Seven”). In the spirit of revolt, Parker and Gillespie seemed to have no choice but to come out with albums titled “Cool Blues” and “Cool Breeze”, respectively. “Cool” came to be associated with the bebop style, a restrained or relaxed style of jazz. Soon, “cool” came to describe those who preferred that kind of jazz, especially in the term “cool cat.” Eventually, “cool” was adopted as a common slang term and its use extended beyond the world of jazz to become a common, general, and informal descriptor of our experiences. A crucial rhetorical move in my argument that educator scholars should give serious attention to “cool” experiences is establishing a conceptual connection to the idea of the sublime. Like the feeling of the cool, the sublime is also associated with intense, moving aesthetic experiences. In fact, Burke called the sublime experiences “the strongest passions.”4 And, while the experience of both the sublime and cool are, in a sense, “beyond words”, the sublime has received considerably more direct attention in philosophy and the arts. Thus, by conceptually linking the cool with the sublime, the 6 The Rebirth of Cool 7 value of these natural, compelling experiences can be developed into a more refined construct for education. The basis for asserting a similarity between cool and sublime experiences is built from an amalgam of etymology, philosophy, poetry, painting, religion, and music. This essay focuses on three common qualities. First, both ideas express a sensation of a chill. One of the definitions of cool is “a somewhat cold temperature”; the feeling of the sublime has been defined by Burke and Kant as “chilling” because it involves awe and terror. Second, both terms are used to describe things of extraordinary quality. One slang definition of cool is “very good”; one definition of sublime is “so awe-inspiringly beautiful as to seem almost heavenly.” Third both terms can describe a serene, connected state of being. An informal definition of cool is “the ability to remain calm in difficult circumstances”; sublime experiences were described as feelings of connection to the natural world by Romantics such as Emerson, Wordsworth, and Thoreau. It is important to remember why finding a connection between two disparate terms is more than an academic exercise. The overarching goal is to be able to better understand the nature of deeply engaging educative experiences in science. I propose that “cool experiences” are a promising place to begin because they are a naturally occurring example of compelling experiences had by all students. However, the idea of the cool needs to be developed conceptually before it can be useful. The idea of the sublime appears to be fruitful not only for the reasons described above, but also because sublime experiences are emotionally charged and compelling and, thus, indicate a high level of engagement and motivation. Furthermore, both cool and sublime experiences are natural, 7 The Rebirth of Cool 8 spontaneous part of everyone’s experience. Finally, the sublime has been associated with great truth and beauty in nature and seems well suited to the goals of science education. Figure 1: Common qualities of the cool and the sublime Common qualities Cool Sublime The sensation of a chill A definition of cool is “a Burke and Kant somewhat cold described the feeling of temperature” sublime as awe: a mix of admiration and terror Extraordinary quality A slang definition of cool is “very good” A definition of sublime is “so beautiful as to seem almost heavenly” A serene, connected state An informal definition of cool is “the ability to remain calm in difficult circumstances” Romantics described the sublime as a feeling of connection, especially to nature General qualities Both cool and sublime experiences are: - emotionally charged and compelling - indicate a high level of engagement - spontaneous and evoked - a natural part of everyone’s experience Cool as the Chill of the Awesome: The Sublime of Burke and Kant Edmund Burke’s ”Philosophical Enquiry into the Origin of our Ideas of the Sublime and Beautiful” is considered to be one of the classic treatments of the sublime. One of the motives underlying Burke’s exhaustive treatment of the subject was a desire to expand the realm of aesthetic experiences beyond what might be called classic or museum art. Burke began with an analysis of the physiological qualities of aesthetic experience then used that as the basis for describing the nature of the beautiful and the sublime.5 This perspective contrasted sharply with more traditional analysis that viewed aesthetics as an 8 The Rebirth of Cool 9 inherent quality of the object. Whereas Burke emphasized sensations of pleasure and pain to distinguish the beautiful and the sublime, classical analysis focused on the art object’s proportion, balance, and coherence. Burke’s aesthetic theory is largely unknown to educational scholarship. However, more than one hundred and fifty years later, John Dewey’s “Art as Experience” presented an aesthetic theory that shared much in common with Burke. As the title implies, art is a quality of the experience, not just the object. As a result, the potential for compelling, transformative experiences is available not only in art museums, but also in everyday settings and with the natural world.6 This assertion is, of course, well known by poets, painters, and, most significantly for our purposes, scientists. How might our students’ conception of “cool” be connected to Burke’s analysis of the sublime? I begin from what must seem like an unusual starting point: both ideas can refer to the perception of lowered temperature. When we experience lowered temperature, we feel a chill. The term “cool” can refer to the perception of temperature, but more important, “cool” may also refer to the “chill” we feel when in the midst of a gripping experiences. The “cool” in these experiences has little to do with actual temperature and, instead, is the natural chill evoked in experiences characterized by deep awe. For example, in the presence of the supernatural, the experience of chills as goosebumps on our skin. Also, our muscles tighten as our body readies for action. These are all physiological manifestations of our fear and awe of a powerful entity. The parallel between the sensation of cool and experience of the sublime is further supported as we appreciate that Burke himself was very much concerned with the physiological basis for sublime experiences. 9 The Rebirth of Cool 10 Thus, this kind of experience that produces a chill and tensing of the body is precisely what Burke would call the sublime. For Burke, sublime experiences are distinguished by a sense of awe, astonishment, and terror. The passion caused by the great and sublime in nature, when those causes operate most powerfully, is Astonishment; and astonishment is that state of the soul, in which all its motions are suspended, with some degree of horror7. The presence of towering cliffs, plunging waterfalls, or vast oceans can evoke feelings of the sublime as we attempt to grasp the magnitude of their size and power. According to Burke, these phenomena are sublime, rather than beautiful, for they cause the body to tense, rather than relax. In a similar vein, the chill evoked by the size or power of natural phenomena was also a defining quality of Kant’s view of sublime experiences.8 For Kant, the sublime is always the integration of awe and terror and emerges in an intellectual or moral way. The aesthetic philosopher Beardsley describes Kant’s sublime as a feeling of grandeur of reason itself and of man’s moral destiny, which arises in two ways: (1) When we are confronted in nature with the extremely vast (the mathematical sublime), our imagination falters in the task of comprehending it…. (2) When we are confronted with the overwhelmingly powerful (the dynamical sublime), the weakness of our empirical selves makes us aware (again by contrast) of our worth as moral beings.9 While fear is a vital quality of sublime experiences for both Burke and Kant, it is essential to appreciate that fear is always united with admiration in the sublime. As a result, in the presence of towering cliffs and vast oceans, the feeling of the sublime is 10 The Rebirth of Cool 11 neither completely aversive, nor completely attractive. Perhaps the term that best describes sublime dread and veneration is “awe”. Interestingly, the word “awe” has origins in the Greek “achos” which means pain. The allure and attraction of sublime experiences is the sense that we feel somehow more perceptive in the experience. The terror is balanced by the pleasure taken in the discovering of our increased capacity to feel and understand. This notion is critical as we consider the implications for science education. For example, the sublime experience of a Class 5 hurricane might be evoked when students are both terrified by its immense power and fascinated as they begin to comprehend the science of extreme weather. If they were to ever actually see a hurricane, they would feel both the aversive force that comes from the fear of being obliterated by an immense power and the exhilaration of coming to understanding it. Good science teaching enables to students to appreciate even more the “awe-some” or “awe-ful” nature of hurricanes. Lest we adopt the dismissive stance that these sublime experiences are the product of either too much thinking by philosophers or too little thinking by aesthetes, it is important to note that scientists throughout the ages have expressed a similar sense of awe. For example, in a written exchange with Einstein, Heisenberg wrote, You must have felt this too: the almost frightening simplicity and wholeness of the relationships which nature suddenly spreads out before us and for which none of us was in the least prepared.10 Similarly, Whewell expressed awe-inspired admiration for the almost incomprehensible magnitude of Newton’s Principia. 11 The Rebirth of Cool 12 As I read the Principia, I feel as when we are in an ancient armoury where the weapons are of gigantic size; and as we look at them, we marvel what manner of men they were who could use as weapons what we can scarcely lift as a burden…11 Although scientists may not feel the deep terror ascribed to the sublime by Burke and Kant, they most certainly feel the sense of awe. From an educator’s perspective, it is important to appreciate that the chill of the awesome is not blind emotion. We do not feel the chill because the awesome is completely beyond our capacity to comprehend. Instead, the experience of this kind of cool is evoked as we sense the precipice of being overwhelmed by the overwhelming. Like the professional surfers who catch the giant winter waves of Oahu’s North Shore, the more we learn, the more we may find humility, reverence, and even fear in the presence of the awesome. However, we also feel a dawning capacity to grasp the awesome. On the bridge between what is within and beyond our grasp, we are filled with ideas and imagination as we traverse back and for the between what is and what could be. This feeling of emerging capacity is at the heart of the sublimely cool experience. It is also learning at it’s most intense. Cool as Insight to the Extraordinary: The Sublime of Transcendent Quality At first, I was deeply alarmed. I had the feeling that through the surface of atomic phenomena, I was looking at a strangely beautiful interior, and felt almost giddy at the thought that I now had to probe this wealth of mathematical structures nature had so generously spread out before me. (Werner Heisenberg on developing a new atomic physics)12 12 The Rebirth of Cool 13 As in his earlier quote, Heisenberg expresses the feeling of alarm that characterizes a sense of awe. Here, Heisenberg’s words reveal another kind of sublime experience – the sublime associated with transcendent quality. Cool and sublime are both used to describe things of extraordinary excellence. When we see or experience something that is very good we may describe it as “cool”. Similarly, in the sublime, we may sense extraordinary quality and perfection. The word “sublime” comes from the Latin words “sub” and “lim”, or “under” and “limit”. In “sublime”, “under” and “limit” are combined to describe that which is lifted up to its highest possible level. The sublime is the exalted. In chemistry, sublimation is the process by which solids transform directly into gas. They “ascend” from their earth-bound form to something more transcendent. Similarly, in psychology, sublimation is the process in which base human impulses are transformed into something “higher”, something more virtuous. Heisenberg was alarmed and giddy as he saw “through the surface” and looked at “a strangely beautiful interior.” His experience was sublime and cool because he was able to see beyond the concrete and ordinary to glimpse what he perceived as transcendent and divine. Longinus, the third century Greek writer, expressed a similar sentiment, “Sublimity is the echo of great minds.”13 Similarity, to have insight is to have sight into something and to apprehend something that seems “beyond” the surface of the appearances. Schopenhauer described it as lifting the “veil of Maya” (the Hindi term for the illusion of the material world) and Kant wrote of “Ding an Sich” (“the world as it is”). Cognitive psychologists discuss the value of learning that focuses on the deep structure of a phenomenon rather than its surface features. The assumption is that truer meaning is 13 The Rebirth of Cool 14 associated with that which lies beyond the surface. Similarly, over two thousand years ago, the ancient Greeks posited the existence of Ideas - transcendent, idealized, prototypical forms - as the basis for the particular, concrete things we experience. Learning was the process of recognizing (recalling, actually) the manifestation of these eternal Ideas in the material world. Thus, in some scientists and philosopher’s experience, sublime insight is a glimpse of the greater truth that lies beyond the surface of things. Jacque Cousteau described what it feels like to catch a glimpse. What is a scientist after all? It is a curious man looking through a keyhole, the keyhole of nature, trying to know what’s going on.14 To experience insight is exhilarating as we feel that we are seeing something truer and more significant than before. Our ordinary experience sublimates into something extraordinary. Whether this experience is a brief glimpse, dawning awareness, or sudden awareness, it is sublime and cool. Good science teachers probably suspect already that this kind of experience may be one of the main reasons why scientific inquiry can be intrinsically engaging. Cool as a Special Way of Being: The Sublime Experience of Connection and Harmony In jazz, cool describes a style popular in the mid-20th century, characterized by a relaxed rhythm. The evolution of the music of Miles Davis highlights distinctive qualities of the cool style. Steeped in the Bebop tradition and taught under the auspice of Bird and others, Miles was now ready to lead. After a few solo records, Miles transformed jazz into its next phase with his BIRTH OF THE COOL sessions, which were 14 The Rebirth of Cool 15 recorded in 1949-50…Stylistically, the cool sound evolved when Lee Konitz joined the band, as suggested by Gerry Mulligan who wanted a lighter sound. "I think what they really meant was a soft sound....Not penetrating too much. To play soft you have to relax... I always wanted to play with a light sound, because I could think better when I played that way."15 The cool sound is relaxed and light. Similarly, in some experience described as “cool” we may feel a sense of extraordinary calm, peace, and harmony. And, as Miles Davis is able to “think better” when relaxed, so too can we perform at a high level when we are cool. Just as music has the power to calm and relax, we might have similar experiences in the realm of the natural world. In the sublime experience of nature, we may find a special way of being: an extraordinary sense of harmony and connection. Davis’ sublime as bebop cool is an interesting contrast to Burke and Kant’s sublime as terror and awe. For Burke and Kant, the sublime feeling emerges from a separation and distance between ourselves and the world that acts on and overwhelms us. By contrast, the sublime of Davis’ “cool” emerges from a sense of connection and intimacy with the world around us. Rather than being “apart from” the world, we are “a part of” our surrounding – just as the improvising trumpeter is, literally, in harmony and “in sync” with other musicians in the ensemble. Although the association of the term cool with a feeling of connection may have been created in the jazz world, this relaxed and harmonious “cool” finds earlier and vivid expression in European and American Romantic poets. In the poetry, literature, and painting of these artists, the beauty of being simultaneously serene and vital in connection 15 The Rebirth of Cool 16 with Nature is a dominant theme. In their work, we find a clear connection between the sublime and the cool. Wordsworth wrote: A sense sublime Of something far more deeply interfused, Whose dwelling is the light of setting suns, And the round ocean and the living air And the blue sky, and in the mind of man, - A motion and a spirit, that impels All thinking things, all objects of all thought, And rolls through all things.16 For Wordsworth, to sense the motion and spirit and impels all things is sublime. Similarly, the sublimity of the experience of dissolving all boundaries between oneself and Nature finds expression in Thoreau. I grow savager and savager every day, as if fed on raw meat, and my tameness is only the repose of untamableness. I dream of looking abroad summer and winter, with free gaze, from some mountain-side,... to be nature looking into nature with such easy sympathy as the blue-eyed grass in the meadow looks in the face of the sky. From some such recess I would put forth sublime thoughts daily, as the plant puts forth leaves.17 And, this poem by the Romantic Jeffer, although horrible and morbid, exalts in the unity between oneself and Nature. I tell you solemnly That I was sorry to have disappointed him. 16 The Rebirth of Cool 17 To be eaten by that beak and become part of him, to share those wings and those eyes What a sublime end of one’s body, what an enskyment; what a life after death.18 In addition to these to the Romantic’s sensibility for the sublime, many others at different times have put to words a similar desire to become part of or connected to other living things is to know the sublime, transcendental, and eternal. Nietzsche implored us to a Dionysian participation with this world, “this monster of energy”.19 Zen Buddhism seeks a oneness between self and Nature. Dewey similarly described the “natural rhythm” that infuses nature, art, science, and aesthetic experiences.20 In the world of science, the sublime experience of intimate connection and harmony also finds expression. Geneticist and Nobel laureate Barbara McClintock not only enjoyed the intimate connection to Nature, but also found this intimate relationship essential to her scientific work. It might seem unfair to reward a person for having so much pleasure over the years, asking the maize plant to solve specific problems and then watching its responses.21 To summarize to this point: In this section I began with the observation that “cool” is a common, spontaneous expression used in compelling experiences and that students seek and enjoy cool experiences. I proposed that these qualities make cool phenomena a potentially valuable source of engaging educative experiences. To develop the idea of the cool to make it a more useful analytical construct, I established connections to the sublime – a construct that has received extensive attention from scholars and artists. In 17 The Rebirth of Cool 18 the next section, I use the conceptual treatment of the cool and sublime to develop specific implications for science instruction. Science Sublime: Educating Students’ Sensibility for the Sublime in Science In his 2002 AERA presentation to the John Dewey Special Interest Group, Elliot Eisner addressed the general question of what teachers should understand about aesthetics. He recommended educators consider the kinds of aesthetic sensibilities that could be developed within particular disciplines. He asserted that a good liberal arts education develops a wide range of aesthetic sensibilities. We study poetry, mathematics, and science because each can develop particular aesthetic capacities. Granted, by studying in different disciplines, we develop factual and conceptual knowledge that helps us in a range of new situations. Rosenblatt refers to this instrumental stance toward learning – emphasizing that it is carried away for later use - as “efferent.”22 Surely science provides us with explanations and facts about the world and this knowledge is important as it informs our actions. However, the purpose of the liberal arts is also to develop our ability to have powerful aesthetic experiences - to appreciate in the Deweyan sense. Science students are not only more able to use what they have learned to solve practical problems, they are also more able to find and respond to cool, sublime experiences. Specifically, science education should enable students to feel the chill of the awesome, to gain a glimpse of extraordinary quality, and to find a harmonious connection to the world. In this section, I describe specific features of what I call “science 18 The Rebirth of Cool 19 sublime” – education aimed at developing students’ sensibility for sublime experiences in science. According to Dewey’s naturalized aesthetics, educative aesthetic experiences can be had with ordinary, everyday things. Similarly, Zen philosophy would have us believe that extraordinary experiences can be had wherever you are, with whatever you’re doing. It would be naïve, however, to fail to acknowledge that such everyday aesthetic experiences are an endpoint and likely to be never fully attained. Therefore, it is essential to find or create special situations that increase the likelihood of sublime experience. What might these situations be? Like an experienced petro-geologist, good teachers know how to improve their chances of making rare and desirable things happen. From the preceding analysis of the sublime and review of the experiences of scientists, I suggest that sublime experiences are more likely to be evoked in three kinds of experiences situations: in experiences with extreme and awesome things, in experiences with things that are extraordinary and rare, and in experiences where there is an intimate connection between the individual and the natural world. Science Sublime: Experience the Awesome Recall the chill of the sublime experience described by Burke. In the presence of things of awesome size and power there is astonishment, “that state of the soul, in which all its motions are suspended, with some degree of horror”.23 We have a natural affinity for things of extreme magnitude or power. The experience of these things is often described as “cool” (and, sometimes we describe cool experiences as “awesome”). The 19 The Rebirth of Cool 20 enduring popularity of the “Guinness Book of World Records” points to our irrepressible fascination for extremes. In the sublime science class, teachers can seek out examples of the extreme within the particular topic of study. For instance, what is the strongest hurricane, the hottest star, or the deepest part of the ocean? Then – and this is the important and the challenging part – teachers can find ways that students might experience as intensely as possible these phenomena. Through vivid words, metaphor, first-hand personal accounts, simulations, and hands-on activities, the teacher might evoke the sublime feeling of awe in the presence of the extreme. Kant describes a few phenomena that could easily become the focus for this kind of sublime science. Prominent, overhanging, menacing cliffs, towering storm clouds from which come lightning flashes and thunderclaps as they roll by, volcanoes in their destructive violence, hurricanes leaving devastation in their trail, the boundless, raging ocean, a lofty waterfall on some might river, all render our capacity to resist insignificantly small in comparison to their power.24 In the Kantian sense, the overpowering experience of the awesome inspires feelings of insignificance, fear, and respect. For some, such sublime insights become the basis for religious faith - in the experience of the awesome - we may feel the presence and power of God. In science class, the intent is not religious awakening, but deeply felt appreciation for Nature that goes beyond the intellectual comprehension. Students may naturally find these extreme events to be “cool”, but when they are experienced as sublimely cool, a greater depth of understanding, feeling, and signification is involved. Swiss mathematician and philosopher put it this way, 20 The Rebirth of Cool 21 The sublime “works on us with hammer-blows; it seizes us and irresistibly overwhelms us.”25 The importance of subject-matter knowledge. At this point, we should consider the potential concern that sublime experiences can be devoid of intellectual substance. This concern arises, I believe, because the intensely emotional and spontaneous nature of sublime experiences leads some to assume that it has little to do with knowledge or thinking. Some may argue that sublime experiences occur independently of the beholder’s depth of scientific knowledge. They may point to the thrill of a rollercoaster ride as an example of an intense experience that occurs relatively independently of the rider’s knowledge of physics. Critical readers may go further to assert that the intensity of an aesthetic experience is, in fact, inversely related to depth of scientific knowledge. In other words, science drains experience of its emotional content. Ironically, this point of view is held by camps on both sides of the divide between science and arts. On the science side, the belief is that emotion only detracts from the main task of doing scientific work. In this view, an activity is scientific to the degree that is coolly objective and rational. On the art side, the belief is that rational processes and conceptual knowledge detract from the having of aesthetic experiences. Even though I am, of course, drawing a caricature of both sides, there has nonetheless been a long history of tension between art and science. I choose not to go into this debate at this time. For one, I believe the debate rests heavily on a weak foundation: the false dichotomy between science and art, and, more generally, between 21 The Rebirth of Cool 22 thought and feeling. Second, excellent treatment of this issue can be found elsewhere, most notably Dewey 26, Jackson27, and Eisner28. A more legitimate concern focuses on the fact that just about anyone will have an intense experience when seeing something awesome, say a Category 5 tropical storm. Critics will correctly point out that the sublime awe and terror described by Burke and Kant are all but automatic responses. Thus, the fact that these feelings are too emotional or too easily had detracts from any suggestion that sublime experiences can be thoughtful, learned, or affected by education. My response is that it is precisely because sublime experiences are intensely emotional and easily had that they are worth our consideration as educators. These kinds of natural and compelling experiences are the ideal starting point for evoking new experiences. I consider emotional intensity to be a necessary, but not sufficient quality of sublime experiences. It is important to reiterate that what I am calling sublime science experiences are inextricably connected to subject matter knowledge. For example, in her classroombased research, Cavanaugh emphasizes that it is only with a knowledge of convection, heat capacity of water, air stream patterns, and so on that students’ experience of the “perfect storm” becomes sublime science.2930 In her work, Cavanaugh makes an important observation: the nature of students’ sublime experiences may change over time. Initially, the experience may be intense but without much knowledge or thought. But, in some circumstances, the sublime experience can be sustained and developed as the individual learns more about the phenomenon. Of course, this kind of development of sublime experiences is the goal of educators. Cavanaugh’s research focuses on science 22 The Rebirth of Cool 23 education and she has called the kind of sublime experiences that are enhanced by conceptual understanding to be the “scientific sublime”. Science Sublime: Experience the Extraordinary The extraordinary and rare has the capacity to fascinate us. We worship the miracle, an event that appears to be contrary to the laws of nature. Haley’s comet, the “perfect storm”, or the Hope Diamond are examples. So are instances of extraordinary human achievement – the perfect game in baseball, a record setting 100 meter dash, the 60 year old woman who gives birth, or the young child who survives for 30 minutes after falling through a frozen lake. Although these things do not defy any scientific theories, they do seem to test our sense of what seems possible. A science sublime curriculum can be organized around this natural affinity and wonderment of ours for the rare and perfect. For example, in Cavanaugh’s sublime science unit organized around the idea of the “perfect storm”, students were simply amazed by the size and destructive power of tropical storms and tornados. Then, they learn about how water temperature, wind conditions, humidity, and a number of other factors have to come together in just the “right” way to produce the storm. They learn that the difference between a massive hurricane and an ordinary storm is to a large degree a matter of a few small differences in what does or does not happen to occur. From this knowledge emerges a sublimely cool experience: a growing appreciation of the extraordinary nature of these phenomena. In our schools, it is unfortunate that students’ understanding of theories and concepts often makes the world merely comprehensible and predictable. Granted, explanations are intended to lead to a life of greater resolution and certainty - progress is often measured 23 The Rebirth of Cool 24 in these terms. However, this alleged gain in certainty is often accompanied by the loss of imagination. Good science teachers understand how to manage the paradox of making the world both more comprehensible and more miraculous. They appreciate that the most sublime experiences emerge from the deepest understanding - that the extraordinary is best appreciated when it is discovered within the ordinary. An appreciation for the extraordinary, rare, and miraculous leads the open mind quickly to the realization that most complex phenomena can be seen in this way. The conception and birth of a child is both understandable and amazing in its complexity. Similarly, the feat of landing a spacecraft on Mars or sending a space shuttle into a geosynchronous orbit is an occasion for the sublime if students can sense the extraordinary complexity and perfection of the operation. Like adults, students have more than likely taken the wonder of technological accomplishment for granted and have lost perspective on how many things must come together in a successful space mission. Only in tragedy are we reminded of the extraordinary nature of this endeavor. Science Sublime: Experience Connection and Harmony with Nature In the presence of the extreme, we may find ourselves at a distance from the object or phenomenon. The extreme may press upon us as a great weight, tower above us at an unreachable height, or be unfathomable in its depth. In this awesome separation, we may feel sublime fear and insignificance that Kant and Burke describe. By contrast, another kind of sublime experience has us feeling of being a part of the world, rather than apart from it. Rather than distance and separation, we feel intimate connection and harmony. Interestingly, to be overwhelmed has two meanings: on the one hand it may mean to be 24 The Rebirth of Cool 25 overpowered or overburdened. On the other hand, it can also mean to be completely engulfed or submerged in something. The third type of sublime, cool experience is characterized by this sense of harmony or connectedness. This sense of sublime was the subject of much of the work of Romantic artists. Emerson provides a typical example. The instincts of the ant are very unimportant, considered as the ant’s; but the moment a ray of relation is seen to extend from it to man, and the little drudge is seen to be a monitor, a little body with a mighty heart, then all its habits, even that said to be recently observed, that it never sleeps, become sublime.31 In the sublime science class, the good teacher understands how to foster the sense of sublime connection between students and natural phenomena. One place to start is by opening students’ eyes to basic similarities shared by all things in Nature. The Challenge of the Romantic Sublime This kind of experience may be the most difficult kind of sublime experience to evoke - more difficult than the extreme and extraordinary sublime already discussed. For example, Cavanaugh’s (2004) classroom-based research designed to educate middle school science students’ sensibility to the interconnection between all things in Nature. In her teaching, Cavanaugh shared her own sublime experiences, modeled this kind of sensibility in class, and shared evocative images and stories. She showed how the subject-matter ideas enabled the sublime, cool sense of connectedness. However, in spite of best her efforts, the Romantic sublime experience was difficult to evoke. For instance, in a discussion on the deep sense of quiet harmony that she had felt on a recent walk in 25 The Rebirth of Cool 26 the deep woods, Cavanaugh’s students were much more concerned about the various dangerous things that might be encountered. Why might this kind of sublime be difficult to evoke? One can speculate about several reasons. The first has to do with developmental factors. Perhaps, the sense of being connected to the natural world relies on the capacity to take on a perspective of the world other than one’s own egocentric view. With age and experience comes an increasing ability to take on other perspectives and to see relationships as interaction rather than uni-directional action. A second challenge may be cultural. Western society has a long history of viewing Nature as something to be feared and avoided. Distinct from Burke and Kant’s sense of awe and admiration, this perspective views Nature as dangerous, dirty, and best kept outside. When we do interact, our relationship is one of overcoming and conquering Nature, rather than finding harmony and interconnection. If students have this predisposition, it is understandable why they have difficulty feeling the kind of kinship and trust in Nature so salient to the Romantic sublime. A third challenge is similarly related to our cultural predispositions. Perhaps, our taste in aesthetic experiences is more inclined toward experiences of greater quantity and magnitude. When we think of “thrill”, we are more likely to be reminded of a supersized, booming I-Max movie of the Grand Canyon than the delicate, luminous body of a jellyfish. The motto “faster, higher, stronger” describes not only to the ancient Greek spirit of the Olympics, but also the modern zeitgeist that pervades economics, consumerism, technology, and even education. Add to that our inclination toward “larger and easier” and you have just about fully described the qualities that guide our 26 The Rebirth of Cool 27 preferences for food, cars, homes, movies, and other elements of our lifestyle. Furthermore, there is a strong pragmatic tradition in US culture that equates the value of experience with how instrumental or useful it is. Thus, the aesthetics of Nature’s harmony is perhaps too subtle, quiet, and pointless for our technological, consumer sensibilities. Lest my analysis subverts the main thesis of my own essay, we should quickly remember that examples of the Romantic sublime abound, especially in science. Wilson32 provides a few examples: Goethe, exemplar of the age, was rightfully respected as poet, botanist, anatomist, physicist, geologist, and meteorologist; Davy, discovered of chemical affinity, pioneer in electrochemistry, wrote verse that gained the respect of Coleridge; Alexander von Humboldt chose to combine botany and travel narrative in his Personal Narrative (1814-25); John Henry Green, the great British anatomist, wrote a book of [9] Coleridgean philosophy, Spiritual Philosophy: Founded on the Teaching of the Late Samuel Taylor Coleridge (1862). Of course, Coleridge, in incorporating the dynamic science of Davy and Oersted into his philosophy and literary theory, and Emerson, who based his theory of the sublime and poetics and rhetoric on scientific fact, avidly participate in this eclectic tradition. According to Rutherford and Ahlgren, the architects of the Science for All Americans reform, one of the basic beliefs in the scientific worldview is that there is a consistency throughout the universe.33 Specifically, the “laws of Nature” – a description of Nature’s nature, if you will - apply in all places at all times. The idea that the universe is a single 27 The Rebirth of Cool 28 unified whole is central to the worldview of scientists as well as Romantics. Emerson wrote: Man is made of the same atoms the world is, he shares the same impressions, predispositions, and destiny. When his mind is illuminated, when his heart is kind, he throws himself joyfully into the sublime order, and does, with knowledge, what the stones do by structure.34 I began by identifying a certain kind of “cool” experience where we feel connected and in harmony with the world around us. Originally a term used by jazz musicians, cool also describes the sublime experience expressed in the art of Romanticism. Although this kind of sublime experience of harmony and interconnectedness may be challenging to evoke in the classroom, I assert that students do have an inclination toward this kind of “cool” experience. The cool experience of performing smoothly as part of ensembles such as choirs, orchestras, sports teams, theater groups, and so on is one example that students’ are familiar with. More generally, they have all experienced “flow”, the optimal experiences described by Csikszentmihalyi35 that come with deep engagement. In these flow experiences, athletes, musicians, artists, and, yes, scientists report that the conscious boundary between themselves and the world is replaced by a powerful sense of connectedness and harmony. 28 The Rebirth of Cool 29 A Few Other Interesting Issues The Sublime Always Exceeds Our Intellectual Grasp Here we come upon an intriguing idea: Might there be a paradox of knowing the sublime? As a distinctly aesthetic experience, the sublime is beyond conceptual and verbal understanding. In schools, and perhaps in science classrooms more than anywhere else, a premium is placed on rational understanding. Certainly, the conceptual and rational enhance our appreciation of aesthetic experiences. However, being overwhelmed by the awesome involves, to some degree, an inability to fully conceptualize and make logical sense. Why does the crushing power of a glacier, the dizzying vastness of our Galaxy, or the exquisite delicacy of a jellyfish overwhelms us? For Kant, we cannot fully intellectualize the sublime: we can sense, but cannot completely comprehend it. These phenomena do not overwhelm young children precisely because they are not inclined to comprehend in the same way as adults. It is important to note that even though an element of incomprehensibility is critical, it is also true that sublime experiences require an element of understanding. Experiences without a sufficient degree of understanding are merely confusing, not sublime. Thus, full comprehension of sublime phenomena is necessarily always just beyond our grasp. Should educators be concerned that an element of incomprehensibility is always present in sublime science experiences? After all, isn’t the goal of education is to reduce uncertainty? The key here is how students experience that which they do not comprehend. There can be confusion, helplessness, or indifference. These are not desirable qualities of educative experiences. Nor, are they qualities of sublime 29 The Rebirth of Cool 30 experiences because in the sublime, the unknown is a source of great fascination, rather than confusion. We feel the allure of that which we cannot fully grasp. According to Kant, the negative feeling of terror in the presence of the overwhelming is accompanied by the positive feeling of being able to grasp it more fully with our imagination and intellect. Thus, even though the sublime has a necessary element that cannot be fully grasped, we are compelled to keep trying to understand it. In my opinion, there can be no better condition for learning. Experience and Knowledge: The Enemies of Sublime Experiences? Here we come to an intriguing issue: what was once sublime, will it stay sublime? If sublime experiences are characterized by an awakening of perception, or inability to comprehend something fully, then how are these experiences affected by the passing of time or the gaining of knowledge? Is it possible for the sublime to remain fresh? For example, when Copernicus asserted that the Earth revolved around the Sun rather than the other way around, the idea was shockingly fresh. The impact of this idea extended from the Catholic Church to the depths of individual psyche. For people seized by this idea, life became fresh and alive. Similarly, in the early days of the motion picture, audiences would scream at the sight of a steam locomotive barreling down the tracks. They would dash from their seats in an effort to get out of the way of the oncoming train. Today, we take for granted the Copernican model of the solar system and the technology of the motion picture, and, as a result, these things no longer evoke the same kind of experience. In these examples, we seem to come to the strange conclusion that experience and knowledge are the enemies of the sublime. 30 The Rebirth of Cool 31 This is no silly conundrum - the product of weak assumptions and wobbly reasoning. The idea that gaining experience and knowledge might diminish rather than enhance what students initially perceive as engaging may actually illuminate why they often find school so boring. Despite our best efforts, education may not make things more engaging to the students; ironically, it may do just the opposite because experience and knowledge can be antithetical to the having of sublime experiences. This situation is most likely to be found when educators emphasize the “grasping” or “acquisition“ quality of learning. We want students to “get it” or to comprehend (the Latin root prehendere means to grasp). Once students “get it”, we ask for them to “carry it” in memory and “give it back” on a test. To carry and deliver something is “to bear” it. It is no surprise that students find this a “bore” (same root as “to bear”. And, perhaps, we may think differently about the saying “That class was a bear.”) Even the wellintentioned educator who wants their students to not only “get it”, but “use it” to accomplish something else contribute to the conundrum. In their perspective, learning school subjects is like earning money in that its value is instrumental. In this view, there is little value in the thing in itself, only in what one can do with it. In fact, any inherent value that may have existed initially is replaced by an instrumental value. I think that students can be put off by this substitution of values, especially when they are not concerned about tests or the things that can be “purchased” with what they learn. Thus, gaining experience and knowledge represents getting, holding, and giving back: boring. How might we escape this conundrum? The following observation from Rothstein is helpful as it simultaneously recognizes the dilemma and moves beyond it. 31 The Rebirth of Cool 32 If I am studying a fugue at the piano, for example, over time, I gradually become more aware of the intertwining voices, sorting them out, singing them to myself. I begin to gasp the sublime without losing sense of its sublimity. I learn to hear even if I am still overwhelmed by what I hear. I’m educated by the sublime …I no longer think of Mozart as sublime in precisely the same way his contemporaries did, because I have become familiar with the effects…This may be true of science as well.36 With the example of his appreciation of Mozart’s music, Rothstein illustrates how gaining experience and knowledge about the music can transform the initial sublime experience into a different kind of experience – one that is still sublime. It seems, then, that knowledge and experience are enemies of the sublime only to the degree that they lead to complacent familiarity. Dewey emphasizes this point when he contrasts the experience of recognition and the experience of perception. Recognition is perception arrested before it has a chance to develop freely...In recognition we fall back, as upon a stereotype, upon some previously formed scheme . . . Recognition is too easy to arouse vivid consciousness.37 In contrast, in perception although we may be looking at something familiar, “there is an act of reconstructive doing: and consciousness becomes fresh and alive.”38 Furthermore, perception like any aesthetic knowing has a pervading emotional quality. Jackson comments on Dewey's views of perception: Dewey's first point is that only as we come to care about objects (feel solicitous about them) do we begin to perceive them. Perception, in other words, is more than noticing or sensing something. It involves feeling as well as sense.39 32 The Rebirth of Cool 33 Thus, knowledge and experience become the inspiration, rather than the enemy, of the sublime as they foster greater caring, perception, and meaning of the sublime thing. Conclusion “Cool” – the unsmiling, serious scholars will dismiss the term. In their view, “cool” is, at best, a sophomoric reaction to something interesting; at worst, it represents the superficiality antithetical to all serious endeavors. My purpose in this essay was to promote a vision of science education where the “cool” occupies a more prominent and important place. When students spontaneously describe something as “cool”, they may well be signaling the having of a powerful aesthetic experience. Yes, “cool” is a common, sometimes empty term. However, the same can be said for “beauty”: even though it is an overused and emotional term, it is nonetheless, “a just tribute to the capacity of the object to arouse admiration that approaches worship.”40 The same applies to the “cool”. I want teachers attend to and foster, rather than reject, these kinds of experiences. I am hoping that we might see that the cool as closely related to the sublime – perhaps, a younger, less developed version of it. As we reconstruct the idea of the cool, perhaps, the good teacher will appreciate how these experiences are the starting and end point, the potential and culmination of worthwhile education. To borrow from Miles Davis, I am suggesting a “rebirth of cool” in education. The chances of success are slim for a cool, sublime science. In short, we love and hate the cool. Perhaps, our ambivalence reflects a tension symptomatic of our time and 33 The Rebirth of Cool 34 culture. Even though we desire to live a life rich in feeling and experience, we also feel the need to be practical and efficient. We seek transcendence in the extraordinary and yet feel the inexorable press of the ordinary and everyday. The idea of the rebirth of cool in science education runs squarely into these ambivalent sentiments. Educators and policy makers will question the value of cool, sublime experiences. They will ask how science sublime prepares students for productive and enjoyable lives. In their view, we care for and educate our children by lading them with things to be used in the life that lies ahead of them. It is difficult to see that from the students’ perspective, school is life, not merely preparation for it. We are unable to see that students spend an immense portion of their days and years in school? We feel a stronger obligation to attend to the quality of their future experiences than to their present experiences. As the saying goes, it is better to teach a person to fish, than to feed the person a fish. As if there had to be a choice. Furthermore, our society is keenly attuned to the tangible, useful qualities of things. We want to have a firm assessment of these qualities because they help us to attend to other obsessions such as achieving, comparing, acquiring, and consuming. Aesthetic experiences, such as the cool and sublime, do not lend themselves to easy comparison to other things. Their exchange and instrumental value is difficult to convert into a familiar currency. They cannot be readily be represented by the quantitative data used in statewide assessments and international comparisons. I reject the crass instrumentalism in education that justifies practice primarily in terms of the amount and “cash-value” of what can be carried away by students. The purpose of gaining experience and knowledge is not to merely take on, carry, and bring forth school 34 The Rebirth of Cool 35 content. If anything, the ideas of school should “carry” the student, rather than the other way around. Furthermore, I urge educators to appreciate the value of the immense value of sublime cool science for both present and future experiences. Dewey reminds us that qualities of tomorrow’s experiences are made available by the experiences we have today.41 I believe the most important predictor of how they will live tomorrow is the quality of their lives today. Thus, educators should seek to enrich students’ present lives by evoking the very qualities that make life worth living: depth of feeling, meaning, and significance. I hope for them to find transcendence in their experience of Nature and feel the cool chill that comes when glimpsing the perfect or the awesome. I make it our mission to inspire science students’ lives with cool, sublime, and beautiful experiences. French mathematician Henri Poincaré perhaps said it best: The scientist does not study nature because it is useful; he studies it because he delights in it, and he delights in it because it is beautiful. If nature were not beautiful, it would not be worth knowing, and if nature were not worth knowing, life would not be worth living. Notes 1 Christopher Sykes, No Ordinary Genius: The Illustrated Richard Feynman (New York: Norton, 1995), 17. 2 John Dewey, Art as Experience (Perigree: New York, 1934), 135. 3 Ibid., 135. 4 Edmund Burke, A Philosophical Inquiry into the Origin of Our Ideas of the Sublime and Beautiful, ed., James Boulton (South Bend, IN: University of Notre Dame Press, 1990), 51. 5 Ibid. 35 The Rebirth of Cool 36 6 Dewey, Art as Experience. 7 Burke, Philosophical Inquiry into the Origin of Our Ideas of the Sublime and Beautiful, 53. 8 Immanuel Kant, Observations on the Feeling of the Beautiful and Sublime, edited by John Goldthwait (Berkeley, CA: University of California Press, 1981). 9 Munroe Beardsley, Aesthetic Inquiry; Essays on Art Criticism and the Philosophy of Art. eds., Monroe Beardsley and Herbert Schueller (Belmont, CA: Dickenson, 1967), 28. 10 Subrahmanyan Chandrasekhar, Truth and Beauty: Aesthetics and Motivations in Science (Chicago, IL: University of Chicago, 1990), 53. 11 Chandrasekhar, Truth and Beauty: Aesthetics and Motivations in Science, 45. 12 Arthur Miller, Insights of Genius: Imagery and Creativity in Science and Art (Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 2000), 383. 13 Cassius Longinus, On Great Writing on the Sublime, translated by, George Grube (New York: MacMillan, 1957). 14 Jacques Cousteau, Christian Science Monitor, July, 1971. 15 Creative Music Archive, http://www.creativemusicarchive.com, Accessed June, 2004. 16 William Wordsworth, “Lines completed a few miles above Tintern Abbey” in The Pedlar, Tintern Abbey, the Two-Part Prelude, Vol. 1, edited by Elizabeth Wordsworth and Jonathan Wordsworth (Cambridge, MA: Cambridge University Press, 1985). 17 Henry Thoreau, Letter, July 21, 1841, to Lucy Brown, in The Writings of Henry David Thoreau, vol. 6, edited by Bradford Torrey and Franklin Sanborn (New York, NY: Houghton Mifflin, 1906), 36-37. 18 Robinson Jeffers, “Vulture” in The Selected Poetry of Robinson Jeffers, edited by Tim Hunt (Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press, 2001). 19 Friedrich Nietzsche, Birth of Tragedy, and The Case of Wagner, translated, with commentary, by Walter Kaufmann (New York, NY: Vintage Books, 1967). 20 Dewey, Art as Experience. 21 Barbara McClintock, On her lifelong research into the genetic characteristics of Indian corn plants which appeared in Newsweek, Oct 1983. 36 The Rebirth of Cool 37 22 Louise Rosenblatt, The Reader, the Text, the Poem: The Transactional Theory of the Literary Work (Carbondale, IL: Southern Illinois University Press, 1978). 23 Burke, A Philosophical Inquiry into the Origin of Our Ideas of the Sublime and Beautiful, 53. 24 Kant, Observations on the Feeling of the Beautiful and Sublime. 25 Johann Georg Sulzer, Swiss mathematician and philosopher, 1790’s. 26 Dewey, Art as Experience. 27 Philip Jackson, John Dewey and the Lessons of Art (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1998). 28 Elliot Eisner, The Enlightened Eye: Qualitative Inquiry and the Enhancement of Educational Practices (New York, NY: Macmillan, 1991). 29 Shane Cavanaugh, Sublime Science: Teaching for Aesthetic Understanding in Middle School Science Classrooms. Unpublished doctoral dissertation, Michigan State University, 2004. 30 Shane Cavanaugh, Sublime Science: Dewey, the Sublime, and Science Education. Paper presented at the annual meeting of the American Educational Research Association, Montreal, Canada, 2005. 31 Ralph Waldo Emerson, Nature. (revised and repr. 1849). Essays and Lectures (Nature: Addresses, and Lectures, Essays: First and Second Series, Representative Men, English Traits, The Conduct of Life) (Library of America). J. Porte (Ed.). Library of America. 1983. Nature, Ch. 4, 1836). 32 Eric Wilson, Emerson’s Science Sublime (St. Martin's Press, 1998). 33 James Rutherford and Andrew Ahlgren, Science for All Americans (New York: Oxford University Press, 1990). 34 Ralph Waldo Emerson, “Worships in The Conduct of Life”. In The Conduct of Life (New York: AMS Press, 1968). 35 Mihaly Csikszentmihalyi, The Psychology of Optimal Experience (New York: Harper & Row, 1990). 36 Edward Rothstein, “Contemplating the Sublime”. In American Scholar, volume 66, page 6, 1997. 37 The Rebirth of Cool 38 37 Dewey, Art as Experience, 52-53. 38 Dewey, Art as Experience, 53. 39 Jackson, John Dewey and the Lessons of Art, 149. 40 Dewey, Art as Experience, 135. 41 John Dewey, Experience and Education. (New York: MacMillan, 1938). 38