Final Report Regional Innovation Systems in Latin America

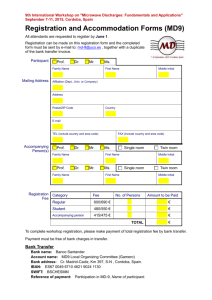

advertisement