mucosal antibiotics

advertisement

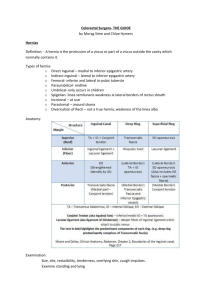

The Small Intestine and Vermiform Appendix Anatomy The small intestine is divided into three regions: duodenum, jejunum and ileum. The duodenum is the first part of the small intestine and most of it is deeply placed on the posterior abdominal wall. It is situated in the epigastric and umbilical regions. It is a C-shaped tube that extends from the stomach around the head of the pancreas to join the jejunum. About halfway down its length it receives the bile and the pancreatic ducts. The jejunum and ileum measure about 6 m. long, the upper two-fifths of this length being the jejunum. The jejunum begins at the duodenojejunal junction and the ileum ends at the ileocecal junction. The coils of jejunum occupy the upper left part of the abdominal cavity, while the ileum tends to occupy the lower right part of the abdominal cavity and the pelvic cavity. The jejunum is larger in diameter, thicker walled, has more prominent plicae circulares (mucosal folds) and has less mesenteric fat than the ileum. The arterial supply to the small bowel is primarily from the jejunal and ileal branches of the superior mesenteric artery. Layers of the small bowel The mucosa is composed primarily of columnar epithelium with goblet cells. The absorbtion of nutrients takes place through the mucosa. The mucosa covers the intestinal villi and has an absorption area of 500 m2. The submucosa is the strongest layer and provides strength to an intestinal anastomosis. It contains nerves, Meissner’s plexus, blood vessels and fibrous and elastic tissue. The muscularis- the muscle layer is composed of an outer longitudinal layer and an inner circular layer with Auerbach’s myenteric plexus. The serosa is the outermost layer and derives embriologically from the peritoneum. Physiology The primary functions of the small bowel are digestion and absorbtion. All ingested food and fluid and also secretions from the stomach, liver and pancreas, reach the small intestine. The total volume may reach 9 l. a day and all but 1-2 l. will be absorbed. Motility Two types of contractions occur following a meal. To-and-fro motion mixes chyme with digestive juices and provides prolonged exposure to the absorbative mucosa. 2. Peristaltic contractions move food distally. Parasympathetic stimulation promotes contractions while sympathetic stimulation inhibits them. Absorbtion Vitamines, fat, protein, carbohydrates, water and electrolytes are all absorbed in the small intestine. Investigations of Small Bowel Disorders Radiology Plain erect and supine abdominal films, whilst invaluable in the diagnosis of acute surgical disorders such as intestinal obstruction and perforations are of limited practical use in the investigation of chronic symptoms referable to the small intestine. Barium sulphate small bowel follow-through is the established investigation designed to outline the small intestine. Small bowel follow-through where the contrast medium is instilled via a long tube directly into the upper jejunum, carries a higher diagnostic yield especially for small bowel tumours, Crohn’s disease and in patients with occult GI bleeding and clinically suspected malabsorbtion. Lesions such as fissure ulcers, sinuses, fistulae, thickening and distorsion of the mucosal folds, polyps are visualized more often by small bowel follow through the long tube and a more accurate prediction of the extent of the disease can be made. The radiological criteria of malabsorbtion are: flocculation and segmentation of barium, thickening of the mucosal folds and dilatation of intestinal loops. However, these changes are non-specific and are frequently encountered in individuals who have no evidence of malabsorbtion. This diagnosis must therefore be confirmed by other specific tests of malabsorbtion. Selective splanhnic angiography is the most reliable method for the detection of angiodysplastic lesions (vascular malformations) which present with episodes of occult bleeding from the GI tract. The bleeding site can be located by this radiological investigation if the patient is bleeding actively at the time of investigation. Ultrasound scanning It has been used in patients with intestinal obstruction and is capable of differentiating fluid-filled dilated intestinal loops from other cystic structures in the abdomen. 3. Isotope Scintigraphy External scintigraphy following the intravenous administration of radiolabelled compounds or isotope-labelled autologous cells,is useful in the investigation of patients with occult GI bleeding or suspected intraabdominal localized inflammation/abscess formation.It is also used to detect inflammed intestine (Crohn’s disease), to estimate the intestinal transit time and to evaluate the function of bilioenteric anastomosis. Estimation of fecal fat The quantitative estimation of fecal fat remains the most sensitive and reliable test of disorders of digestion and absorbtion. On a standard diet containing 80-100 g. of fat, the fecal fat output normally is less than 6 g./day. Jejunal Mucosal Biopsy Apart from abnormalities of villus architecture (subtotal villus atrophy in celiac disease ) abnormal mucosal pathogens may be detected as in Whipple’s disease. Schilling Test In the Schilling test, radiolabelled vit.B12 is given orally after a large parenteral injection of the unlabelled vit.to ensure saturation of the body store. Normal subjects will excrete 10% or more of radiolabelled vit. in the urine. Breath Tests These simple and easily executed investigations are used for the detection of bacterial overgrowth, the demonstration of carbohydrate malabsorbtion and in the assessment of the small bowel transit. Hydrogen Breath Tests This can be used for measurement of small bowel transit time and bacterial overgrowth. Repeated measurements of the H2 in the end-expiratory air taken every few minutes after ingestion of a meal. When the head of the meal reaches the cecum, the resulting bacterial fermentation induces a sustained rise in the breath H2 concentration. Strictly speaking the test measures the oral-cecal transit time which includes the gastric emptying time.However, if the meal is radiolabelled with Tc 99,both gastric emptying and small bowel transit times can be calculated from the one investigation. In patients with bacterial overgrowth, the fasting H2 level in the expired breath is elevated. The investigation of a patient with suspected malabsorbtion should commence with estimation of the fecal fat. 4. Once steatorrhoea is confirmed in this way, further tests are required to establish the nature of the underlying pathology. In the end malabsorbtion will be found to be either of small bowel origin (small intestine disease, bacterial overgrowth) or the result or pancreatic exocrine insufficiency. Syndromes Resulting from Disease or Surgery on the Gastrointestinal Tract These include bacterial overgrowth, the short-gut syndrome and protein-losing enteropathy. Bacterial Overgrowth In this syndrome, the small intestine becomes colonized by bacteria. There is an increase in the concentration of organisms which are normally confined to the lower small bowel and colon. The affected intestine becomes inflammed, edematous and dilated. The syndrome may result from surgery or disease which results in excess bacteria entering the small intestine or from delayed clearance of bacteria from the small bowel due to stasis. In some cases, the bacterial overgrowth develops in the absence of a readily demonstrable local cause. This may occur in patients with malnutrition or immune deficiency. The increased bacterial population deconjugates the intraluminal bile salts. These bile salts participate poorly in the emulsification of fat and they are passively absorbed to a certain extent, resulting in a reduced concentration of bile salts in the lumen when malabsorbtion of fats and fat-soluble vitamins ensues. The bacteria also bind vitamin B12 and convert it to inactive derivatives. The result is megaloblastic anemia. There is some malabsorbtion of carbohydrates and proteins, although this is rarely severe. The bacteria also metabolize the triglycerides, forming hydroxy fatty acids which are known to impair the absorbtion of water and sodium by the intestinal mucosa acting like laxatives. This together with the action of the deconjugated bile salts, enterotoxin and the osmotic load generated by the fermentation of the major dietary components, all add up to a multifactorial and potent cause for the diarrhea in these patients. Causes of bacterial overgrowth 1. Excessive entry of bacteria into the small intestine - achlorhydria- absence of bactericidal gastric acid - gastro-jejunostomy - partial/total gastrectomy - enterocolic fistulas - cholangitis - loss of the ileocacal valve following right hemicolectomy 5. 2. Intestinal stasis - stenotic Crohn’s disease - stenotic intestinal tuberculosis - small bowel diverticulosis- stasis - afferent loop stasis - entero- enteric anastomosis - diabetes mellitus- autonomic neuropathy - radiation enteritis- stenosis, impaired intestinal motility - scleroderma- impaired intestinal motility Clinical features In the first instance, the patient may exhibit symptoms referable to the underlying pathology: postgastrectomy symptoms, recurrent intestinal colic due to subacute obstructing lesions. The symptoms and signs of bacterial overgrowth itself may be non-specific, and include asthenia, nausea and vomiting, excessive bowel sounds and weight loss. Diarrhea is a frequent symptom and is usually watery. Other clinical features include glossitis, anemia, hypoproteinemia with peripheral edema, tetany. Paresthesiae and peripheral neuropathy may be found in association with vit.B12 deficiency. Treatment Surgical treatment of the underlying condition, whenever possible is the definitive and curative treatment. Situations are frequently encountered, however, where surgical treatment is not advisable because of the extensive jejunal diverticulosis, scleroderma. In these cases,intermittent therapy with oral antibiotics is often beneficial (tetracycline and metronidazole). The antibiotic course is usually administered for 10-14 days at a time. Short-gut Syndrome This is the most serious form of intestinal decompensation and is encountered after massive resection of the small bowel and in some patients subjected to jejuno-ileal by-pass for morbid obesity. The lesions which may necessitate extensive resection of the small intestine in order of frequency are: - Crohn’s disease - mesenteric infarction - radiation enteritis - multiple fistulas - small bowel tumours 6. Crohn’s disease is by far the commonest cause. This disease often necessitates repeated resections over a number of years culminating in the short-gut syndrome. It is often stated that resections of more than half of the small bowel length are invariably accompanied by serious malabsorbtion. Thus patients with a residual small bowel length of less 2 m. have a diminished work capacity and those with less than 1 m. require home parenteral nutrition on an indefinite basis. Ileal resections are less well tolerated than jejunal resections, largely because the active transport sites for bile salts and vit.B12 are localized in the ileum. The clinical outcome following intestinal resection is dependent on the following:- extent and site of resection - age of the patient - physical and mental condition Treatment In patients with massive small bowel resection, indefinite total parenteral nutrition via a permanent tunnelled silicone feeding line is the only option available for survival. The regimen must provide 40 Kcal/Kg. body weight. In patients with about 1 m.of small bowel the weaning from parenteral nutrition is possible. The remaining small bowel will hypertrophy with time. Oral nutrition is based on an elemental diet which contains only components that are directly absorbed by the intestinal mucosa without any enzymatic digestion. It contains no residue. Antiperistaltic agents should be given. Gastric hypersecretion should be controlled with H2-receptor antagonists. Fat and watersoluble vitamin supplementation is needed. Parenteral vit.B12 is needed if the distal ileum has been resected. Protein-losing Enteropathy A greatly increased loss of plasma proteins is found in the syndrome of proteinlosing enteropathy. When severe, it leads to hypoproteinemia and secondary hyperaldosteronism with water and salt retention. The clinical picture is dominated by the manifestation of the underlying disease. The disorders associated with protein-losing enteropathy fall into three categories: 1. mucosal disease: - celiac disease - Whipple’s disease - bacterial infection and parasitic infestations of the GI tract 7. 2. ulcerating lesions and tumours: - multiple gastric ulcers - malignant gastric tumours - colonic cancer and villous tumours - gastro-jejuno-colic fistula - radiation enteritis 3. lymphatic obstruction - primary lymphangiectasia - intestinal lymphoma - congestive cardiac failure The treatment is that of the underlying pathology which may necessitate surgical intervention. If the plasma albumin is very low (less than 3 g/l) this must be restored to near normal by protein infusions. Tumours of the Small Intestine Tumours of the small intestine are rare and all the benign and malignant types account for less than 10% of all GI neoplasms. Benign neoplasms contitute 60% of small bowel neoplasms and they are usually asymptomatic. 1. Polyps 1. a. Adenomatous polyps are rare in the small intestine. They may be seen in the familial polyposis syndromes and have malignant potential in this setting. 1. b. Hamartomatous polyps are found in patients with Peutz-Jaghers syndrome (mucocutaneous pigmentation accompanied by widespread intestinal polyposis). There is no malignant potential in this syndrome. 2. Other benign tumours Benign tumours in the small intestine might be: leiomyomas, lipomas, hemangiomas, fibromas and neurofibromas. The commonest presentation of benign small bowel tumours is with intestinal obstruction due to intussusception. Chronic blood loss from a benign small bowel tumour may cause an irondeficiency anemia and occasionally vascular tumours may give rise to overt GI bleeding. There are usually no significant findings on physical examination. Treatment of the asymptomatic cases is by local excision. 8. Malignant Neoplasms of the Small Intestine The commonest tumours are adenocarcinomas, carcinoid, lymphoma and metastases from distant malignancies. Malignant tumours usually present with bleeding, diarrhea, perforation or obstruction. Diagnosis is frequently made late in the course of disease as symptoms are insidious in onset. Treatment is segmental resection, including adequate margins proximally and distally and as much mesentery as possible without compromising the blood supply to the remaining small bowel. Adenocarcinoma These are usually well-differentiated mucus-secreting tumours which are more common in the proximal part of the small intestine. They spread primarily to the regional lymph nodes, liver and peritoneal cavity. Patients with resectable tumours have a 25% 5 year-survival rate. Carcinoid tumours are derived from enterochromaffin cells. These cells are part of the amine precursor uptake and decarboxylation system (APUD cells) and hence carcinoid tumours are classified as apudomas. Carcinoid tumours are commonest in the appendix, the ileum and rectum. Carcinoid syndrome-flushing, diarrhea, bronchoconstriction is caused by serotonin and other vasoactive substances secreted by the tumour. Diagnosis is made by finding elevated levels of 5-hydroxyindolacetic acid (5 HIAA), the breakdown product of serotonin in the urine. Treatment includes resection of the primary tumour and resection of metastases. Liver metastases can be resected (when solitary) but usually require palliative therapy with intra-arterial chemotherapy or hepatic arterial ligation or embolization to decrease the blood flow to the metastases. Gastrointestinal stromal tumors are the most common mesenchymal gastrointestinal malignancy. The peak incidence of this sarcoma seems to occur between 40 and 60 years of age, with men and women equally affected. In the past this tumor was misdiagnosed as leiomyoma, leyomyosarcoma or leyomyoblastoma. As the clinical course of the disease can last for 10 to 15 years, the prevalence of GIST is higher than its incidence. Circumstances of detection: symptomatic 69%, incidental 21% and autopsy 10%. Advances in modern immunohistochemistry for KIT now allow GIST to be distinguished from other histopathologic subtypes of GI sarcomas. All GIST have malignant potential and can become metastatic. Over 90% of reported cases express KIT, a type III transmembrane receptor tyrosine kinase. CD 34 is expressed in 60-70%, of cases and desmin is rarely present in GIST. In contrast, true smooth-muscle tumors often express high levels of desmin and smooth-muscle actin. 9. Prior to imatinib mesylate, surgery was the only effective treatment for GIST. Tumor size at presentation predicts recurrence-free survival; patients with tumors more than 10 cm. have a 5-year survival rate of 27% while those with tumors less 5 cm. have a 5 year survival rate of 82%. High mitotic index increases the likelihood of recurrence. Imatinib selectively inhibits the tyrosine kinase activity of KIT, responsible for tumor growth. Diverticulosis Duodenal diverticula are common but over 90% are asymptomatic;70% of duodenal diverticula are in the periampullary region and they cause cholangitis, pancreatitis and recurrent common bile duct stones. Jejunal diverticula are rare; they may cause obstruction, bleeding or perforation. They may also cause malabsorbtion due to bacterial overgrowth within the diverticulum. Meckel’s diverticulum is the commonest diverticulum of the GI tract.It is located within 40 cm. of the ileocecal valve. Most symptomatic Meckel’s diverticula are seen in childhood, usually causing bleeding. The bleeding is from heterotopic gastric mucosa in the diverticulum, causing”peptic”ulceration in adjacent ileal mucosa. Problems in adults include bowel obstruction, bleeding and acute diverticulitis which may be indistinguishable from appendicitis. Treatment If symptomatic, resection of the diverticulum with enteroraphy. Acute appendicitis It is the commonest condition requiring acute abdominal surgery. Incidence The peak incidence of this disease is in the second and third decades of life. Etiology 1. Obstruction of the lumen of the appendix is the principal cause. - fecaliths are the commonest cause of obstruction - less common causes include: - lymphoid hypertrophy - intestinal worms - cecal cancer 2. Persistent appendiceal mucosal secretions,gradual distention with inflammation of the appendix, bacterial overgrowth and if the condition is allowed to progress, ischemia, gangrene and perforation follow obstruction of the lumen. Diagnosis is based on the history, physical examination, laboratory findings. 10. History The classic history includes pain as the prime symptom. The pain begins in the epigastrium, gradually moves to the periumbilical region and finally over a period of 1-12 hours localizes in the right lower quadrant. This pain sequence may differ considerably from the above description, especially in light of the varied anatomic locations of the appendix. Anorexia is a second prominent symptom and is nearly always present to some degree. Vomiting occurs in about three/fourth of the patients. The sequence of symptoms is important in contributing to the diagnosis. Anorexia followed by pain and then by vomiting, when it occurs is the classic course. Physical examination Physical findings depend primarily on the stage of the disease and the location of the appendix. Temperature and pulse are only slightly elevated early in the disease. Higher elevations may indicate a complication such as perforation or abscess. Pain on palpation over McBurney’s point is usually when the appendix is located anteriorly. When is located in the pelvis, abdominal findings may be minimal and only rectal examination may yield significant findings. Abdominal muscle guarding and rebound tenderness reflect the stage of the disease since progression is associated with peritoneal irritation. Several signs, if present, assist in the diagnosis: - Rowsig’s sign is pain in the right lower quadrant on palpation of the left lower quadrant. - psoas sign is pain on extension of the right thigh with the patient lying on the left side. - obturator sign is pain on internal rotation of the flexed right thigh with the patient supine. Laboratory studies A moderate leukocytosis with a predominance of neutrophils is usual. A normal WCC does not rule out appendicitis. The differential diagnosis for right quadrant pain includes: 1- mesenteric lymphadenitis 2- regional ileitis-Crohn’s disease-flare up 3- pelvic inflammatory disease 4- gastroenteritis 5- ruptured ovarian cyst 6- urinary tract infection or urinary tract calculi 7- cecal or sigmoid diverticulitis 11. Treatment Appendicectomy is the treatment of choice. Preoperatively, broad-spectrum antibiotics are indicated to lessen the incidence of postoperative wound infection. Antibiotics are usually continued for 5-7 days postop. for cases of appendiceal rupture with abscess formation. Antibiotics are continued for 7-10 days for cases of appendiceal rupture with diffuse peritonitis. Complications Clinical course Left untreated some cases of appendicitis proceed to perforation. Following perforation the contents of the abdominal cavity will attempt to contain the process forming an inflammed mass of matted intestine and omentum. This may progress to a fibrous walling off of a collection of pus secondary to the rupture and appendiceal abscess. If the body’s attempts to contain the perforation are unsuccessful, the entire abdominal cavity may become contaminated causing a diffuse peritonitis. Significant temperature and pulse elevation, marked leukocytosis and findings typical of peritoneal inflammation with or without a mass in the right lower quadrant, indicate perforation. The mass may sometimes be appreciated only on rectal examination. Appendiceal perforation significantly increases postop. morbidity and mortality rates. The approach to acute appendicitis should be timely intervention to prevent progression to this complication. Abdominal ultrasonography may assist in the differential diagnosis of a right iliac fossa mass. Treatment of perforated appendicitis includes iv antibiotics and hydration and surgical intervention including appendicectomy and abscess drainage. The timing of such intervention is individualized to each patient. Study questions 1. What are the appropriate investigations for small bowel disorders ? 2. What are the causes of bacterial overgrowth into the small intestine ? 3. List the causes of intestinal stasis ? 4. An young female patient comes in with RIF pain, nausea, loss of appetite, dizziness. She is pale, systolic BP of 90 cm. Hg., PR of 100/min. She is got 2 weeks delayed periods and dysuria. How do you manage this patient? 5. What does signify GIST ?