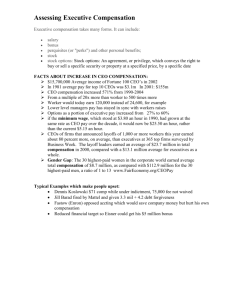

Eight Local Hospital Officials got 1M in 2010

advertisement

Eight Local Hospital Officials got $1M in 2010 By Cathey O’Donnell and Jane Lerner, LoHud.com, February 12, 201 Eight executives from 15 Lower Hudson Valley hospitals received more than $1 million in salary, bonuses, benefits and other pay in 2010 at a time when the state struggled to control health-care costs. A Journal News analysis of tax records shows they included CEOs and top physicians who earned five times more than a cap ordered last month by Gov. Andrew Cuomo for nonprofit organizations, a move to restrict the amount of state money they can use on executive compensation to $199,000 a year. Million-dollar salaries have raised the ire of Cuomo, who also ordered that 85 percent of state hospital funding, including Medicaid, must go toward patient care and services by 2015. Three executives received more in total compensation than Westchester Medical Center CEO Michael Israel, who earned $1.3 million and oversees a hospital that’s more than twice the size of other facilities in the region. In all, 177 top employees from 14 of the nonprofit hospitals in Westchester, Rockland and Putnam earned more than the governor’s cap, which has focused attention on the pay packages of top administrators whose agencies get state Medicaid money. The Journal News obtained the 2010 federal tax form 990 from the hospitals, which like all nonprofits must provide the information to maintain their tax-exempt status. The high hospital salaries, as well as Cuomo’s call to rein them in, come as the health-care system faces increased scrutiny as part of a national reform movement and debate over soaring costs. “Health care is already expensive,” said Judy Wessler, co-director of the Commission on the Public’s Health System, a New York City advocacy group. “Paying these huge salaries can jack up the cost of providing health care for everyone.” A Journal News analysis of hospital-executive compensation for 2010 has revealed: The highest-paid hospital employees include White Plains Hospital CEO Jon Schandler with $1.6 million in total compensation, Dr. Edward Lundy at Good Samaritan Hospital in Suffern with $1.48 million and Edward Dinan, CEO of Lawrence Hospital in Bronxville, with $1.41 million. Others in the million-dollar range include John Federspiel, president of Hudson Valley Hospital Center in Cortlandt; Joel Seligman, CEO of Northern Westchester Hospital in Mount Kisco; and Keith Safian, CEO of Phelps Memorial Hospital Center in Sleepy Hollow. A year earlier, Federspiel received a compensation package of nearly $2 million due partly to an $800,000 deferred compensation payout. The average CEO compensation rose 13 percent from 2009, to $939,751. Ten hospitals paid $7.7 million in bonuses to top executives, an increase of 15 percent over 2009. White Plains Hospital alone distributed $2.1 million in bonuses, including $650,000 to Dr. Jesus Jaile-Marti, chief of neonatology, and $575,000 to Schandler. Nearly 2,000 hospital employees, or just over 9 percent of the total workforce in the region, earned more than $100,000 in 2010. The high salaries also come as hospitals pressure many employees for wage freezes, rising insurance costs and watered-down pensions, said Deborah Elliott, a nurse and deputy executive officer of the New York State Nurses Association, a statewide union representing nurses at Sound Shore, Mount Vernon, St. John’s Riverside, St. Joseph’s and Nyack hospitals as well as Westchester Medical Center. “It never ceases to amaze me that we sit at the bargaining table with these executives who are making $1 million and they give us such a hard time about a half-percent increase for a nurse who is making $63,000,” Elliott said. “It’s galling.” Because Westchester Medical Center is a public-benefit corporation, it does not have to file a nonprofit tax form. However, The Journal News filed a Freedom of Information request for Israel’s compensation, which rose $71,724, or 6 percent, from 2009 to 2010 despite the hospital reporting a $100 million loss in revenue over the past several years. Though the medical center has hired an outside firm to determine executive compensation, most other local hospitals rely on their boards of trustees or a special committee to determine how much to pay their top administrators. With many pay packages topping $1 million, many hospital executives, including Federspiel, opt to defer some of their pay, which can provide more immediate tax benefits. Edward B. MacDonald Jr., chairman of Hudson Valley Hospital Center’s board of directors, said Federspiel deserves his paycheck. The hospital has earned a profit for 22 of the 25 years that Federspiel has been at the helm and has expanded both its services and payroll in that time, he said. “He’s the best administrator, planner and motivator I have ever had the privilege to work with,” MacDonald said. “I wish I could pay him more.” While a handful of CEOs earned seven-figure packages, others on staff also received top salaries and bonuses, such as Lundy, a cardiac surgeon, and Dr. Stephen Heier, a gastroenterologist at Phelps, who received $1 million in compensation. “Excessive salaries are like pornography,” said Doug Sauer, CEO of the New York Council of Nonprofits, an industry group. “You know it when you see it. It shocks your consciousness.” Cuomo’s order doesn’t mean hospitals suddenly will stop paying seven-figure salaries. It just means they can’t use state money to pay for them. “It has nothing to do with capping salaries or controlling salaries,” Sauer said. “It has to do with bookkeeping.” High-paying not-for-profits, such as hospitals, will find ways around the regulation by shifting money that does not come from the state to continue to pay high salaries, he predicted. Paying for talent 2 Across the region, hospital officials defend the salaries as the price institutions have to pay to retain top talent. At least one industry group, the Greater New York Hospital Association, has told its members that they can obtain a waiver from compliance with the cap. “At a certain level, I don’t think it’s unrealistic for the state to ask how this money is being spent,” said Kevin Dahill, executive director of Northern Metropolitan Hospital Association, an industry group. “But I would be hard pressed to think that this governor or any other will have the right to start dictating terms regarding compensation.” Jaile-Marti, the neonatology chief at White Plains Hospital, got the $650,000 bonus in 2010, the highest in the region, even as officials eliminated bonuses to executives because of the recession. The hospital was contractually obligated to provide bonuses for doctors who met specific quality measures, spokeswoman Dawn French said. Though longevity is expensive, high turnover can be even costlier. Good Samaritan paid a total of more than $2 million to four top administrators in 2009, including a CEO who had resigned the previous year and one who served for just a month during a tumultuous year in which the hospital lost $4.9 million. One of the CEOs, Terence O’Brien, served just eight months but was paid a total of $1.4 million over two years. In many communities, including New Rochelle and Suffern, hospitals also serve as key employers that can help determine the fate of the local economy. Mount Vernon Hospital, which posted its first profit in at least three years, laid off 100 employees, including 20 doctors and 27 nurses, in 2010. And over a two-year period, Sound Shore Medical Center in New Rochelle, which is part of a network that includes Mount Vernon, cut its workforce by nearly 9 percent. For 18 months, St. John’s Riverside in Yonkers suspended bonuses and pay increases as it weathered the economic recession. That changed in mid-2010 when the hospital instituted 3 percent raises after a corporate restructuring. These days, executive compensation at St. John’s is based on six criteria, with financial performance being just one of them, said Denise Mananas, the hospital’s spokeswoman. “It can’t just be about the money,” Mananas said. “It’s got to be about patient care, it’s got to be about the doctors, it’s got to be about how well we serve the community. It’s all of those things and more.” Last month, St. John’s rewarded its entire workforce for turning around the financial picture of the hospital, which is expected to report a $10 million profit this year, by giving everyone from laundry workers to the CEO a $50 bonus, Mananas said. Other hospitals have revamped their salary structures. Blythedale Children’s Hospital in Valhalla altered its pay structure last year by giving lower across-the-board salary increases, supplementing them with incentive-based bonuses and eliminating the ability for employees to accumulate unused vacation time. All managers at St. Joseph’s Medical Center in Yonkers received a pay cut of 1 percent, including the president, because of its financial problems. Officials said in a statement they are unsure whether there will be salary increases for anyone on staff this year. But when it comes to compensation, the size of the facility doesn’t necessarily correlate to the amount its leaders earn. Dinan, the CEO of Lawrence Hospital, which has 291 beds, got a 26 3 percent raise between 2008 and 2010 when he earned $1.4 million in compensation. Hospital officials would not comment on his salary or those of the other 14 executives. At the same time, the CEO of Putnam Hospital Center, roughly the same size as Lawrence, earned half of Dinan’s compensation in 2010. Critics say the price of health care isn’t the only casualty when it comes to high salaries for those organizations that are supposed to be nonprofit. “Nonprofits exist because of the public’s trust and the privilege of a tax exemption,” Sauer said. “Excessive salaries erode the public’s confidence and hurt everyone.” 4