Bryn and Kelly 14

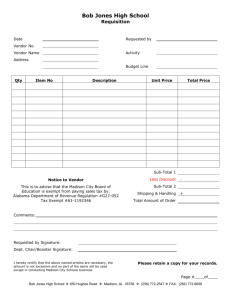

advertisement

Bryn P. and Kelly K. To the People of the State of New York: Rhetorical Analysis: WE HAVE seen the necessity of the Union, as our bulwark against foreign danger, as the conservator of peace among ourselves, as the guardian of our commerce and other common interests, as the only substitute for those military establishments which have subverted the liberties of the Old World, and as the proper antidote for the diseases of faction, which have proved fatal to other popular governments, and of which alarming symptoms have been betrayed by our own. All that remains, within this branch of our inquiries, is to take notice of an objection that may be drawn from the great extent of country which the Union embraces. A few observations on this subject will be the more proper, as it is perceived that the adversaries of the new Constitution are availing themselves of the prevailing prejudice with regard to the practicable sphere of republican administration, in order to supply, by imaginary difficulties, the want of those solid objections which they endeavor in vain to find. The opening greeting establishes the genre of this document as an open letter, which appropriately fits the intention of the author, James Madison, in that it appeals to a vast, varying audience. The error which limits republican government to a narrow district has been unfolded and refuted in preceding papers. I remark here only that it seems to owe its rise and prevalence chiefly to the confounding of a republic with a democracy, applying to the former reasonings drawn from the nature of the latter. The true distinction between these forms was also adverted to on a former occasion. It is, that in a democracy, the people meet and exercise the government in person; in a republic, they assemble and administer it by their representatives and agents. A democracy, consequently, will be confined to a small spot. A republic may be extended over a large region. To this accidental source of the error may be added the artifice of some celebrated authors, whose writings have had a great share in forming the modern standard of political opinions. Being subjects either of an absolute or limited monarchy, they have endeavored to heighten the advantages, or palliate the evils of those forms, by placing in comparison the vices and defects of the republican, and by citing as specimens of the latter the turbulent democracies of ancient Greece and modern Italy. Under the confusion of names, it has been an easy task to transfer to a republic observations applicable to a democracy only; and among others, the observation that it can never be established but among a small number of people, living within a In his first paragraph, Madison aims to evoke an since of emotional concern (pathos) from his audience prior to explaining his specific intention. Through the use of anaphora, Madison lists several metaphorical interpretations, each of which concerns the personal welfare of citizens as well as the general welfare of the general population, for the role of the Union in the everyday life of an American. As Madison introduces his purpose for this letter, he employs all three types of rhetorical appeals. First he personifies “the Union” in his initial introduction of his argument in order to detract from the overall rigid, political sentiment of his letter (pathos). Next the use of the words “observations on this subject” suggests a calculated, even scientific, approach to the analysis of his argument and its opposition (logos). Finally, Madison asserts his own credibility (ethos) through his discrediting of his “adversaries[’]” warped perspective, beliefs, and actions, punctuated by alliteration as well as diction. Specifically the alliteration of the words “prevailing,” “prejudice,” and “practicable” accentuates the mal-intent and absurdity of his opponents’ actions, demonstrated through describing them as “imaginary difficulties…they endeavor in vain to find.” Here, again, Madison establishes his own credibility (ethos) by referring to his (and others’) previous works on the subject. Also, by invoking the first person, Madison establishes a common connection among himself, the subject, and his audience, but more importantly he uses a logical analysis (logos) of the confusion between democracy and republicanism, accentuating the difference through antithesis, to explain his position from an objective, thus generally more effective, angle. Also the use of the conjunction “and” between the words “assemble” and “administer,” as well as the alliteration, implies an equality of the two properties, subtly showing Madison’s preference toward democracy for the purposes of his argument. Madison’s carefully chosen diction, specifically the words “accidental” and “celebrated,” and “great,” creates a commonly effective technique used in persuasive orations: by not outwardly denouncing the beliefs of his opponents, rather implying their defects, Madison makes his assertion less offensive to a nonlikeminded reader, therefore making it more easily acceptable to that portion of his audience (logos). Additionally, the use of alliteration to connect the words, “accidental…added…artifice” heightens the sense of his opponents’ unintentional incorrectness. This technique also appeals to the pathos of the audience. Next, by comparing his opponent to the monarchs of Europe, though in a positive light, Madison still creates a negative emotional connotation about his opponents (pathos). By repeating the word “confusion,” Madison again softens any impulse opposition to his position by, again, illustrating opposing opinion as mistaken rather than simply incorrect (logos/ pathos). Madison also conveys his definition of democracy versus republicanism through the repetition of the word “small.” small compass of territory. Such a fallacy may have been the less perceived, as most of the popular governments of antiquity were of the democratic species; and even in modern Europe, to which we owe the great principle of representation, no example is seen of a government wholly popular, and founded, at the same time, wholly on that principle. If Europe has the merit of discovering this great mechanical power in government, by the simple agency of which the will of the largest political body may be concentred, and its force directed to any object which the public good requires, America can claim the merit of making the discovery the basis of unmixed and extensive republics. It is only to be lamented that any of her citizens should wish to deprive her of the additional merit of displaying its full efficacy in the establishment of the comprehensive system now under her consideration. As the natural limit of a democracy is that distance from the central point which will just permit the most remote citizens to assemble as often as their public functions demand, and will include no greater number than can join in those functions; so the natural limit of a republic is that distance from the centre which will barely allow the representatives to meet as often as may be necessary for the administration of public affairs. Can it be said that the limits of the United States exceed this distance? It will not be said by those who recollect that the Atlantic coast is the longest side of the Union, that during the term of thirteen years, the representatives of the States have been almost continually assembled, and that the members from the most distant States are not chargeable with greater intermissions of attendance than those from the States in the neighborhood of Congress. That we may form a juster estimate with regard to this interesting subject, let us resort to the actual dimensions of the Union. The limits, as fixed by the treaty of peace, are: on the east the Atlantic, on the south the latitude of thirty-one degrees, on the west the Mississippi, and on the north an irregular line running in some instances beyond the forty-fifth degree, in others falling as low as the forty-second. The southern shore of Lake Erie lies below that latitude. Computing the distance between the thirtyfirst and forty-fifth degrees, it amounts to nine hundred and seventy-three common miles; computing it from thirty-one to forty-two degrees, to seven hundred and sixty-four miles and a half. Taking the mean for the distance, the amount will In this paragraph, Madison continues with his logical analysis of the mistaken definitions of democracy and republicanism by casually inserting an ironic attribution of democratic representation to the Europeans to whom he just previously attributed monarchy. Following this statement, however, Madison presents a logical if-then structure to his argument to reestablish his claim to the superiority of the American republican government. Madison reinforces his logical argument by creating an emotional connection between republicanism and patriotic Americanism, thus creating a feeling of obligation for Americans to support a republican government (i.e. Madison’s position). Most notable in this section are Madison’s diction and personification: “lamented” and “deprived” and “her.” Madison presents and refutes some of the perceived flaws of his argument beginning in this paragraph and continuing into the following. In debunking specific opposition to his argument, Madison further asserts his credibility and the validity of his argument (ethos). The argument still maintains a sense of logical organization in the use of “as” and “so.” Furthermore, Madison presents a rhetorical question that is key to his argument, and seemingly in the same breath, he answers it, further establishing the foundation of his argument by logically bolstering his own credibility. Also in this instance, Madison uses “the greater” scheme for logical invention by deducing the effectiveness of the large boundaries of a republic from the properties of the small boundaries of a true democracy. By returning to the first person in this paragraph, Madison again creates a connection among himself, his audience, and his subject, but in this specific instance, using the word “we” increases the emotional connection among all parties but also further establishes Madison’s credibility by reiterating his own investments in the country and therefore his personal concern for its wellbeing. The use of the word “actual” also lends itself to the logical (i.e. factual) basis of Madison’s argument. Madison continues his logical appeal throughout the paragraph by presenting factual statistics about the size of the Union and its effect on the efficacy of the proposed republican government. Use and repetition of the word “computing” additionally adds to the precise, mathematical foundations of this part of Madison’s argument; however, by discussing the irregularities of the Union’s boundaries and subsequently creating calculations based on averages, Madison precludes any possible counterargument that his data are skewed, thus creating a practical, credible foundation for this portion of his argument as well. be eight hundred and sixty-eight miles and threefourths. The mean distance from the Atlantic to the Mississippi does not probably exceed seven hundred and fifty miles. On a comparison of this extent with that of several countries in Europe, the practicability of rendering our system commensurate to it appears to be demonstrable. It is not a great deal larger than Germany, where a diet representing the whole empire is continually assembled; or than Poland before the late dismemberment, where another national diet was the depositary of the supreme power. Passing by France and Spain, we find that in Great Britain, inferior as it may be in size, the representatives of the northern extremity of the island have as far to travel to the national council as will be required of those of the most remote parts of the Union. Favorable as this view of the subject may be, some observations remain which will place it in a light still more satisfactory. Herein Madison continues his logical, mathematical analysis through comparison with European countries (thus refuting them as possible pieces of evidence for his detractors). Additionally, this comparison shows a logical assessment in proving that similar scenarios to the proposed republican government in America have been previously effective in Europe. This comparably short paragraph, which stands clearly marked from its surroundings, transitions the article from its general introduction to an enumeration of specific points. The careful construction of the paragraph, or rather sentence, creates a cliffhanger effect, causing an reader to desire to continue reading and discover what could possibly be “still more satisfactory.” In the first place it is to be remembered that the general government is not to be charged with the whole power of making and administering laws. Its jurisdiction is limited to certain enumerated objects, which concern all the members of the republic, but which are not to be attained by the separate provisions of any. The subordinate governments, which can extend their care to all those other subjects which can be separately provided for, will retain their due authority and activity. Were it proposed by the plan of the convention to abolish the governments of the particular States, its adversaries would have some ground for their objection; though it would not be difficult to show that if they were abolished the general government would be compelled, by the principle of selfpreservation, to reinstate them in their proper jurisdiction. For the remainder of the article, Madison enumerates his four specific points using a simple first-second-third method of organization. Cleverly, Madison uses the word “enumerated” in this paragraph, subtly accentuating his premise of organization. By explaining the jurisdiction of the government under the proposed government, Madison simultaneously illustrates the possibility of republican government to effectively govern a large area and dismiss several of the fundamental arguments against the principle of a republican government. Also, by asserting that a republic would, in fact, not be preferential to any particular group, Madison addresses popular ethical concerns about a republic. Also by dispelling a situation in which the federal government were to abolish the state governments (by demonstrating their mutual reliance on one another), Madison provides a logical answer (logos) to another ethical concern (pathos). Furthermore, the use of the subjunctive mood in this scenario, conveys the unlikelihood of the situation altogether. A second observation to be made is that the immediate object of the federal Constitution is to secure the union of the thirteen primitive States, which we know to be practicable; and to add to them such other States as may arise in their own bosoms, or in their neighborhoods, which we cannot doubt to be equally practicable. The arrangements that may be necessary for those angles and fractions of our territory which lie on our northwestern frontier, must be left to those whom further discoveries and experience will render more equal to the task. Continuing with his logical organization, Madison does not understate, but rather over simplifies the purpose of the Constitution, again, to make it seem more feasible. Additionally, Madison applies a mathematical lexicon to his writing, further implying a calculated, precise nature of the Constitution. Let it be remarked, in the third place, that the In this paragraph, Madison addresses other Federalist concerns (internal improvements) in light of the possible new Constitution. intercourse throughout the Union will be facilitated by new improvements. Roads will everywhere be shortened, and kept in better order; accommodations for travelers will be multiplied and meliorated; an interior navigation on our eastern side will be opened throughout, or nearly throughout, the whole extent of the thirteen States. The communication between the Western and Atlantic districts, and between different parts of each, will be rendered more and more easy by those numerous canals with which the beneficence of nature has intersected our country, and which art finds it so little difficult to connect and complete. A fourth and still more important consideration is, that as almost every State will, on one side or other, be a frontier, and will thus find, in regard to its safety, an inducement to make some sacrifices for the sake of the general protection; so the States which lie at the greatest distance from the heart of the Union, and which, of course, may partake least of the ordinary circulation of its benefits, will be at the same time immediately contiguous to foreign nations, and will consequently stand, on particular occasions, in greatest need of its strength and resources. It may be inconvenient for Georgia, or the States forming our western or northeastern borders, to send their representatives to the seat of government; but they would find it more so to struggle alone against an invading enemy, or even to support alone the whole expense of those precautions which may be dictated by the neighborhood of continual danger. If they should derive less benefit, therefore, from the Union in some respects than the less distant States, they will derive greater benefit from it in other respects, and thus the proper equilibrium will be maintained throughout. I submit to you, my fellow-citizens, these considerations, in full confidence that the good sense which has so often marked your decisions will allow them their due weight and effect; and that you will never suffer difficulties, however formidable in appearance, or however fashionable the error on which they may be founded, to drive you into the gloomy and perilous scene into which the advocates for disunion would conduct you. Hearken not to the unnatural voice which tells you that the people of America, knit together as they are by so many cords of affection, can no longer live together as members of the same family; can no longer continue the mutual guardians of their mutual happiness; can no longer be fellowcitizens of one great, respectable, and flourishing empire. Hearken not to the voice By discussing both of his agendas in a light of co-dependency, Madison creates an easily accessible sense of necessity for both items. He continues to use mathematical diction, but also his diction , specifically “beneficence of nature,” portrays the canal system as not only useful but also as a natural progression in development. Despite the concern of his time over the excess of power of the Federal government, especially with regards to internal improvement, Madison indiscreetly neglects to address such concerns. Madison continues to build to a climax in his letter. In this paragraph, Madison introduces a new metaphor for the Union, comparing it to a body with a “heart” and “circulation,” a common oratory practice, which immediately evokes sentiments of livelihood (as well as spiritedness). In this section, Madison addresses the logical concern over the unequal distribution of benefits to the states, but as opposed to previous sections, he presents an emotionally based response. First, Madison implies that all states are interconnect through his metaphor of “circulation,” but then he creates a logical assessment of the differing needs of the states. In response to his own assessment, Madison proceeds to answer using certain frightening diction to illustrate an emotional basis for his logical argument. Madison’s concluding sentence returns to pure logical deduction, supported by further use of mathematical (scientific) diction. In this lengthy conclusion, Madison again returns to the first person, illustrating the mutual investment in the prosperity of the Union shared by his “fellow citizens and him. While flattering his audience and their good judgment, Madison reiterates the “error” of his opponents through melodramatic diction. By connecting the idea of good judgment with the “error” of his opponents, Madison immediately compels his sagacious audience to prefer his proposal to the other, if even subconsciously, again apply an effective oratory technique to his letter. As in the first paragraph, Madison uses anaphora, in this instance to illustrate the power and conviction of his declaration and returns to metaphor (of knitting in this case) to illustrate the interconnectedness (all the lines of his motif of co-dependence) of appendages of the Union. Madison also simultaneously creates a metaphor of the Union as a family as well as the repetition of the word “mutual” to increase the emotional attachment of his audience and further demonstrate his motif. which petulantly tells you that the form of government recommended for your adoption is a novelty in the political world; that it has never yet had a place in the theories of the wildest projectors; that it rashly attempts what it is impossible to accomplish. No, my countrymen, shut your ears against this unhallowed language. Shut your hearts against the poison which it conveys; the kindred blood which flows in the veins of American citizens, the mingled blood which they have shed in defense of their sacred rights, consecrate their Union, and excite horror at the idea of their becoming aliens, rivals, enemies. And if novelties are to be shunned, believe me, the most alarming of all novelties, the most wild of all projects, the most rash of all attempts, is that of rendering us in pieces, in order to preserve our liberties and promote our happiness. But why is the experiment of an extended republic to be rejected, merely because it may comprise what is new? Is it not the glory of the people of America, that, whilst they have paid a decent regard to the opinions of former times and other nations, they have not suffered a blind veneration for antiquity, for custom, or for names, to overrule the suggestions of their own good sense, the knowledge of their own situation, and the lessons of their own experience? To this manly spirit, posterity will be indebted for the possession, and the world for the example, of the numerous innovations displayed on the American theatre, in favor of private rights and public happiness. Had no important step been taken by the leaders of the Revolution for which a precedent could not be discovered, no government established of which an exact model did not present itself, the people of the United States might, at this moment have been numbered among the melancholy victims of misguided councils, must at best have been laboring under the weight of some of those forms which have crushed the liberties of the rest of mankind. Happily for America, happily, we trust, for the whole human race, they pursued a new and more noble course. They accomplished a revolution which has no parallel in the annals of human society. They reared the fabrics of governments which have no model on the face of the globe. They formed the design of a great Confederacy, which it is incumbent on their successors to improve and perpetuate. If their works betray imperfections, we wonder at the fewness of them. If they erred most in the structure of the Union, this was the work most difficult to be executed; this is the work which has been new modelled by the act of your convention, and it is that act on which you are now to deliberate and to decide. In this section, Madison returns to the body metaphor of the Union, which he subtly connects to his readers through mention of their own body parts. Madison’s melodramatic language continues through this section of the paragraph, and as he builds toward a climax, Madison uses asyndeton to leave his assertion still feeling incomplete, compelling readers to continue. Also, notably, Madison has entirely stopped making logical appeals to his audience, demonstrating that he has already outlined his argument and now in his conclusion, he seeks to thoroughly impress it in the mind of his audience. Madison continues his appeal to the pathos of his audience through two rhetorical questions. In contrast to his previous rhetorical question, which was intended to illustrate a logical concept, Madison does not answer these questions so as to leave his audience to ponder them. Also in this section Madison appeals to the ethos of his audience through an allusion to the Declaration of Independence. Madison employs antithesis to illustrate two contrasting concepts of the Union and the government. Again through melodramatic diction (as well as the less important metaphor of weight), Madison demonstrates the inadequacy of the alternatives to both the American Revolution and now the formation of a republican government. Though the appeal may seem logical, the reference to the Revolution and the patriotic emotions associated therewith in conjunction with the proposition of a republican government makes the appeal most effective on an emotional level. Madison also introduces the idea of the infancy of the idea of republicanism, hence there is no previous model to guide it, in order to refute and lessen claims based on the flaws of the republican system. This notion becomes the foundation of Madison’s final assertion: that it is the duty of Americans to form a more perfect Union, as it were, through convention on the Constitution. Madison does not conclude his letter forcefully, but rather simply presents all of the benefits of his proposal in comparison to all of the demerits of his opponents’ proposal, leaving the people to deliberate and decide. By avoiding an overt imposition of his own proposal on his audience, Madison applies one final oratory technique to his letter: the audience will more likely accept his proposal, rather than resist it, because Madison does not force them down a metaphorical path but rather leads them to a fork and allows them to choose the better of the, which he has clearly demonstrated to be his rather than that of his opponents.