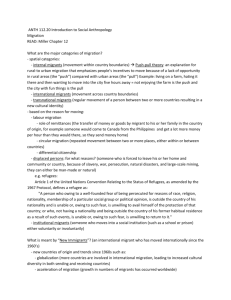

GENDER AND MIGRATION - Bridge - Institute of Development Studies

advertisement