The Gambia Education Sector Medium term Plan 2008-2012

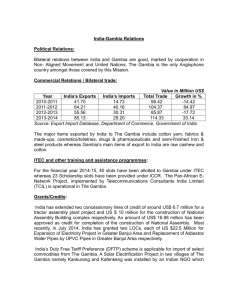

advertisement